Insider Brief

- Researchers affiliated with Aegiq report coordinated advances that aim to remove three core barriers to large-scale photonic quantum computing: probabilistic entanglement, exponential software compilation and low tolerance to light loss.

- The system combines near-deterministic generation of entangled photon states with a teleportation-based method for executing quantum operations without heavy qubit routing or deep gate decomposition.

- The architecture targets large simulation workloads in chemistry, materials and fluid dynamics but still requires experimental validation of its error-correction thresholds, photon efficiency and large-scale integration.

- Image: Aegiq

Quantum engineers are reporting progress on three wicked — if not wickedest — problems blocking large-scale photonic quantum computers: unreliable entanglement, runaway software complexity and sensitivity to light loss.

In an announcement, an Aegiq-led team of researchers report on a set of coordinated advances that shows, a credible path toward building photonic machines that grow from thousands of qubits into the millions, which is a threshold widely viewed as necessary for practical, fault-tolerant quantum computing.

The system — referred to as QGATE by the researchers — focuses on a core weakness in photonic quantum computers, which use particles of light as qubits. Photons travel easily through fiber and operate at room temperature, but they have proved difficult to entangle reliably and even harder to scale into large, error-corrected machines. The physics of light itself has imposed steep efficiency penalties as systems grow.

The findings across these studies — posted here and here on the pre-print server arXiv — suggest that photonic quantum computers may be closer to escaping those limits than previously thought.

“With QGATE, we improve quantum compute runtimes, reduce compile time from an exponentially scaling problem to one that scales linearly, and show the path to improved quantum error correction thresholds for photonic loss,” the team writes in the announcement. “Along with our deterministic photon sources, which can reduce the number of physical components required by several orders of magnitude, we are breaking through the key barriers to scaling quantum computing.”

Why Photonic Quantum Computing Has Stalled

According to the researchers, most photonic quantum computers follow a model in which large webs of entangled photons — known as cluster states — are created first, and then computation is performed through carefully chosen measurements. The approach avoids applying long chains of direct quantum logic gates, but it shifts the engineering burden onto building those entangled webs in the first place.

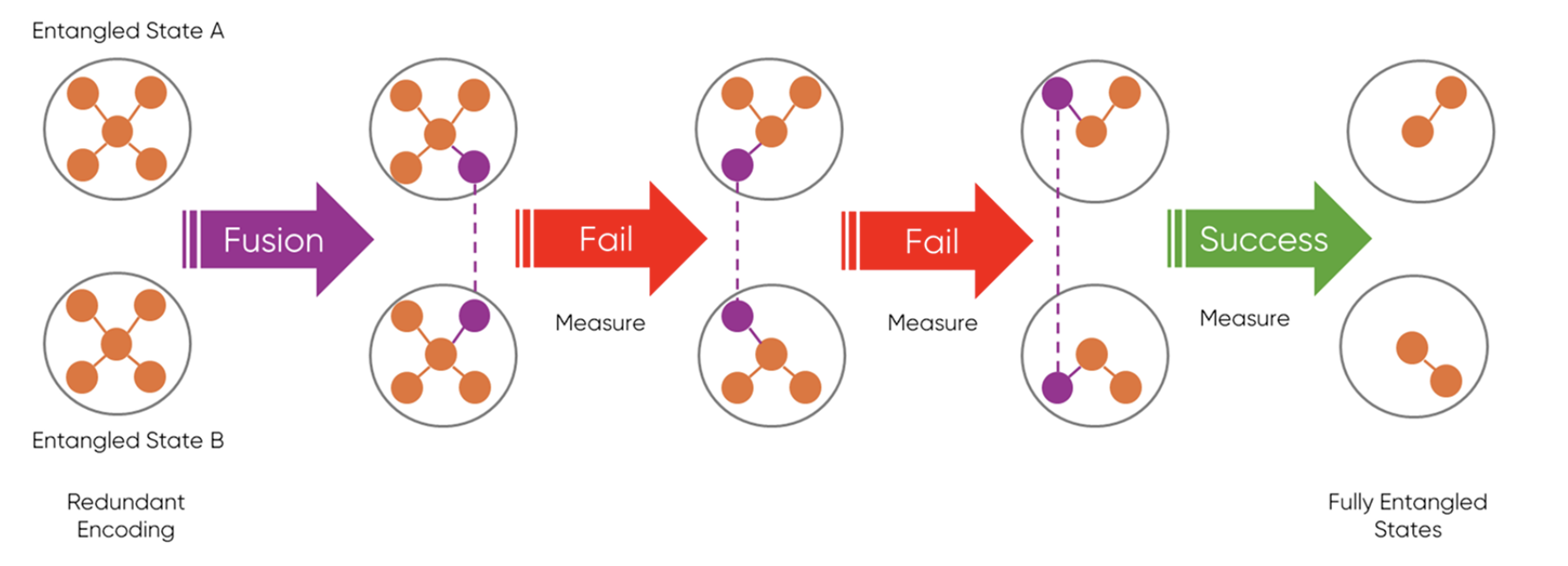

For more than two decades, the main method for stitching small photonic clusters into large ones has relied on a probabilistic process. Each attempt to join two clusters succeeds only about half the time. When it fails, photons are destroyed and the system must start over.

As a result, the number of components required to build a large machine rises sharply, often faster than engineers can realistically support.

At the same time, even when hardware improves, most quantum software must still be broken down into vast numbers of basic operations before it can run. That compilation step grows exponentially for many important algorithms in chemistry, materials science and fluid simulation.

On today’s machines, the cost of preparing those instructions can cancel out any advantage quantum hardware might offer.Photonic systems face a third structural hurdle as well: light loss. Every mirror, waveguide and detector absorbs some fraction of photons. If too many are lost, the quantum computation fails.

Most photonic error-correction schemes tolerate only modest losses before breaking down, the researchers suggest.

Addressing Three Limits at Once

The team reports that the new results could address all three limits.

On the hardware side, the researchers report progress toward creating entangled photonic building blocks in a deterministic way. Instead of relying on random photon pairs generated by nonlinear crystals, the system uses semiconductor quantum dots as on-demand light sources. Each dot emits single photons at precise times, allowing engineers to construct small, highly entangled groups of photons intentionally rather than by chance.

Those groups use redundant encoding, meaning each logical unit of quantum information is spread across multiple photons. If one photon is lost or a fusion attempt fails, the logical unit can survive and the entanglement attempt can be repeated. In system-level terms, this converts a process that once succeeded only half the time into one that can, in principle, approach near-certainty.

Researchers working on the platform estimate that this shift could cut the physical overhead of photonic quantum error correction down to a few hundred photons per protected logical qubit, which is a level that begins to resemble the scale targeted in superconducting and trapped-ion systems.

On the logical side, the team introduces a measurement-driven method for running quantum operations through teleportation rather than direct gate application. Instead of forcing qubits to interact physically through narrow hardware connections, the system prepares special helper states in advance. By measuring those helpers in specific ways, the desired quantum operation appears on the data qubits indirectly.

This approach eliminates the need to route qubits across a device using chains of swap operations. Working with qubits this way is a major source of delay and error in most architectures. It also allows complex quantum operations to be applied directly, without being broken down into long sequences of basic logic steps.

From a software perspective, this changes how quantum programs scale, according to the researchers. The conventional process of decomposing algorithms into millions or billions of primitive gates can grow exponentially with problem size. By contrast, the teleportation-based method allows compilation to grow in a linear fashion for large classes of operations, according to the system design.

These advances suggest a photonic platform that is not only easier to build physically, but also easier to program at useful scale.

What the System Could Enable

If the methods perform as expected in hardware, it’s possible that this changes the economics of several high-value quantum applications.

Large-scale simulations of molecules and materials depend on deep quantum circuits and long-range connections between qubits. The same is true for fluid dynamics problems used in aerospace and energy systems. These workloads have remained out of reach because today’s machines cannot sustain long calculations without excessive error growth.

By combining near-deterministic entanglement, high tolerance to light loss and simplified execution of multi-qubit operations, the photonic approach could support these calculations with far fewer physical components than earlier designs required.

The platform is also built around standard optical fiber and telecom-grade hardware, making it naturally suited to modular systems. Instead of concentrating all qubits inside a single cryogenic chamber, photonic processors could be linked across racks or rooms using light, allowing systems to grow by network expansion rather than monolithic construction.

What Remains Unproven

There is still work that remains at the architecture and protocol stage, the papers suggest.

The near-certain entanglement rates depend on achieving exceptionally high photon efficiency across emitters, waveguides, filters and detectors. Even small losses compound rapidly when millions of photons are in play. Maintaining that efficiency outside laboratory conditions remains an open engineering challenge.

The system’s tolerance to light loss is also based on error-correction thresholds derived from architectural analysis. Those thresholds still require experimental validation at scale. Building and operating large arrays of quantum dots with uniform performance is another unresolved hurdle.

On the software side, the claimed reduction in compilation complexity assumes that future control systems and compilers can fully exploit the teleportation-based model. That layer remains under active development.

Where the Field Goes Next

Photonic quantum computing has long been viewed as a complex, but potentially valuable path toward large quantum machines. Its natural compatibility with fiber networks, room-temperature operation and direct integration with classical optics gives it structural advantages that other platforms lack. But until now, its scaling barriers have appeared equally structural.

By tackling these key bottlenecks — primarily physical entanglement limits and logical execution — all at once, the researchers suggest this reframes that balance. Instead of trading hardware simplicity for software complexity, it proposes a system in which both layers become easier to scale at the same time.

The next step is addressing the limitations to determine how seriously photonic systems can compete with other modalities as companies move toward fault-tolerant quantum computing.

The Aegiq team posted summaries of the two arXiv papers in their announcement on the advances:

“Generating redundantly encoded resource states for photonic quantum computing” describes a novel protocol compatible with our world leading quantum dots to overcome the limitations of probabilistic two qubit gates in photonics, enabling the building blocks for a fundamentally new approach to addressing scalability challenges in quantum computing.

“QGATE (Quantum Gate Architecture via Teleportation & Entanglement)” increases performance by (a) reducing the number of operations the quantum computer needs to perform, (b) reducing compile time for large quantum operations (an often overlooked and exponential scaling problem that can negate any advantage from quantum hardware) to a linear scaling problem, and (c) achieving up to 26% error correction thresholds to photon loss in the system.

For a deeper, more technical dive, it’s recommended that you review the papers on arXiv and the technical paper on the Aegiq website. It’s important to note that arXiv is a pre-print server, which allows researchers to receive quick feedback on their work. However, it is not — nor is this article, itself — official peer-review publications. Peer-review is an important step in the scientific process to verify results.