Insider Brief

- An a16z researcher argues that while long-term encrypted data faces real quantum risk today, most cryptographic systems are not imminently threatened by quantum computers.

- He finds that post-quantum encryption warrants immediate deployment for sensitive data, but post-quantum digital signatures and blockchain systems require slower, deliberate migration due to performance and security trade-offs.

- The analysis concludes that implementation bugs and governance challenges pose far greater near-term risks than a cryptographically relevant quantum computer.

- Image: Photo by geralt on Pixabay

Timelines for a quantum computer powerful enough to break modern cryptography are being widely overstated, and that exaggeration is driving costly and in some cases misguided security decisions, according to an analysis by Justin Thaler, a research partner at a16z and an associate professor of computer science at Georgetown University.

Thaler’s assessment, published in the a16z blog, draws a distinction between where the quantum threat is real and urgent, where it is distant and where it is often misunderstood entirely. He asserts that society must act decisively in some areas, such as protecting long-term confidential data from “harvest now, decrypt later” attacks, while resisting the temptation to rush into risky and immature cryptographic changes where no immediate quantum threat exists. The danger, he writes, is not that quantum computers will arrive tomorrow, but that misplaced urgency today could weaken systems through bugs, poor implementations, and premature lock-in to fragile security schemes.

“These distinctions matter,” writes Thaler. “Misconceptions distort cost-benefit analyses, causing teams to overlook more salient security risks — like bugs.”

According to Thaler’s definition, cryptographically relevant quantum computer would be a fully fault-tolerant, error-corrected machine capable of running Shor’s algorithm at a scale sufficient to break widely used public-key systems like RSA-2048 or the elliptic-curve cryptography that underpins most blockchains. Despite high-profile claims to the contrary, he argues there is no public evidence that such a machine is close to reality.

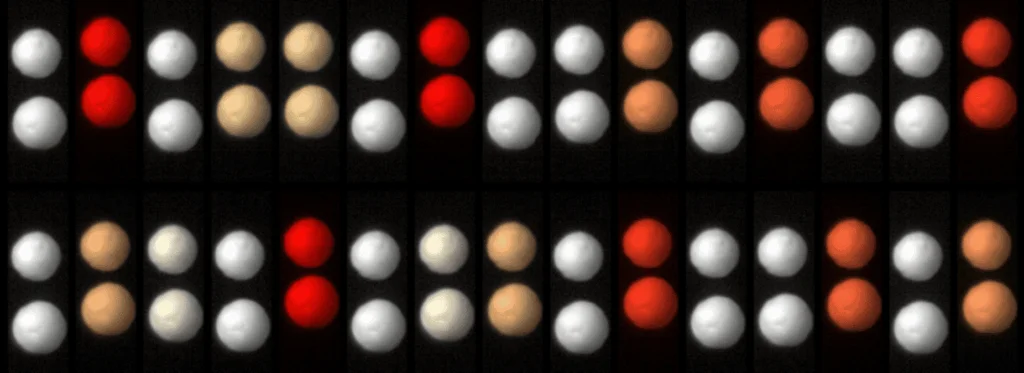

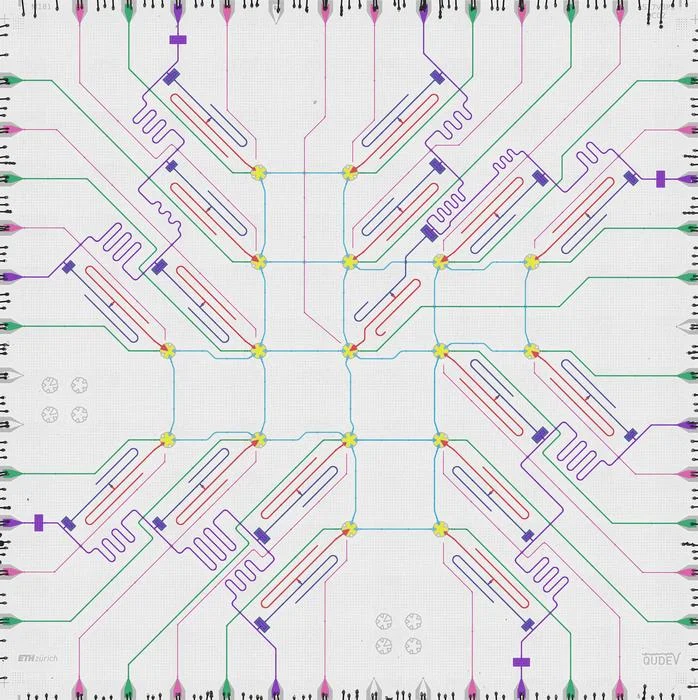

Across today’s leading quantum architectures — trapped ions, superconducting qubits, and neutral atoms — no system approaches the hundreds of thousands to millions of physical qubits that would be required, after error correction, to execute cryptographically meaningful attacks. Even more important than raw qubit counts are gate accuracy, the ability for qubits to interact, and the depth of error-corrected computation that can be sustained without failure. While some machines now exceed 1,000 physical qubits, their error rates and connectivity remain far short of what cryptanalysis would demand.

The gulf between laboratory demonstrations and a machine that could threaten global cryptography remains vast, Thaler writes. Researchers have only demonstrated a handful of stable, error-corrected logical qubits — and none with the depth needed to support long and complex algorithms. Both qubit numbers and reliability would need to improve by multiple orders of magnitude before cryptanalysis becomes practical.

Yet public perception of progress is frequently distorted because claims of “quantum advantage” often refer to contrived problems engineered specifically to run on current hardware rather than to tasks of practical value, Thaler writes.

Announcements of thousands of qubits frequently refer to quantum annealers, which are not suitable for running Shor’s algorithm at all. He claims that, further, the term “logical qubit” is sometimes stretched beyond recognition. In proper fault-tolerant systems, a single logical qubit typically requires hundreds or thousands of physical qubits. Some recent announcements have applied the label to arrangements that can detect errors but not correct them, creating a misleading impression of readiness.

Even the most optimistic recent comments from leading quantum theorists refer only to the possibility of tiny, symbolic demonstrations of fault-tolerant computation, not machines capable of breaking real-world cryptographic systems, Thaler writes. Factoring the number 15 under full fault tolerance would be a scientific milestone, but it would pose no practical threat to global security. Factoring modern cryptographic keys is a fundamentally different scale of challenge.

Thaler indicates that the U.S. government’s 2035 target for widespread adoption of post-quantum cryptography in federal systems as a reasonable planning horizon, but not as a forecast that quantum computers capable of breaking encryption will exist by then. He emphasizes that excitement about hardware progress is not incompatible with a decade-plus timeline before cryptographic risk becomes acute.

Where the Quantum Threat Is Immediate

The most urgent quantum risk today does not come from active decryption but from the quiet collection of encrypted data for future use. Thaler writes the threat of “harvest now, decrypt later” attacks, in which adversaries store encrypted communications today with the expectation of decrypting them once a powerful quantum computer becomes available. Nation-state adversaries are almost certainly already archiving large volumes of sensitive traffic from governments and critical institutions, he suggests.

That reality makes immediate action unavoidable for systems that require long-term confidentiality. Even if a cryptographically relevant quantum computer arrives decades from now, data that must remain secret for 10, 20, or 50 years is already at risk. For these cases, the performance overhead and implementation challenges of post-quantum encryption are outweighed by the certainty of eventual exposure if action is delayed.

As a result, major technology platforms have already begun deploying hybrid encryption schemes that combine classical and post-quantum methods. Web browsers, content delivery networks, and messaging applications such as iMessage and Signal now layer new post-quantum mechanisms on top of proven classical ones. This approach allows them to block future quantum attacks while retaining current-day security if a new post-quantum scheme later proves flawed.

Encryption and Digital Signatures

Thaler offers a distinction, however, between encryption and digital signatures. Encryption protects secrecy; digital signatures prove authenticity. Only encryption is vulnerable to harvest-now-decrypt-later attacks. Signatures created today do not conceal information that can be retroactively extracted by a future quantum computer. If a cryptographically relevant quantum computer arrives tomorrow, it could enable signature forgery going forward, but it would not retroactively invalidate signatures created in the past.

This distinction is often missed in public debate, Thaler says, and it leads to inflated urgency for post-quantum signatures where none yet exists. The consequences are nontrivial because post-quantum signature schemes are larger, slower, harder to implement, and more prone to subtle flaws than today’s elliptic-curve systems.

Zero-knowledge proofs, whixh are widely used in blockchain scaling and privacy systems, sit in the same category as signatures with respect to quantum risk. Even when built on elliptic-curve cryptography, their zero-knowledge property remains secure against quantum adversaries. There is no hidden secret to harvest for later decryption. Only once a cryptographically relevant quantum computer exists could attackers begin forging false proofs going forward. Past proofs remain valid, Thaler writes.

These distinctions shape how quantum risk applies to blockchains. Most non-privacy blockchains, including Bitcoin and Ethereum, rely primarily on digital signatures for transaction authorization, not encryption. Their public ledgers contain no confidential data to retroactively decrypt. As a result, they are not exposed to harvest-now-decrypt-later attacks, despite repeated claims to the contrary.

Privacy-focused blockchains are different in that systems that hide transaction recipients, amounts, or links between transactions do rely on encryption and related tools that could be broken retroactively. For these chains, quantum risk is more immediate and the severity depends on how much information can be reconstructed from the public ledger alone. Thaler suggests that these platforms should prioritize a transition to post-quantum cryptography sooner if performance allows, or redesign their architectures to avoid placing decryptable secrets on-chain in the first place.

“Bitcoin’s Special Headaches”

Bitcoin occupies a unique and uncomfortable position in the post-quantum debate, according to Thaler. Although it is not exposed to harvest-now-decrypt-later attacks, he identifies two non-quantum forces that make early planning essential: slow governance and abandoned funds.

“The quantum threat to Bitcoin is real, but the timeline pressure comes from Bitcoin’s own constraints, not from imminent quantum computers,” Thaler writes.

Thaler sees Bitcoin changing slowly even under ideal conditions. Any consensus shift on cryptography risks triggering disputed hard forks that could fracture the network. Unlike many modern blockchains, Bitcoin also cannot rely on passive migration. Owners must actively move their coins to new addresses to adopt new signature schemes. Coins that are abandoned — and Thaler points out that estimates place these in the millions, worth hundreds of billions of dollars — cannot be protected once they become vulnerable to quantum attacks.

The quantum threat to Bitcoin would not unfold as a sudden collapse. Shor’s algorithm must attack public keys one at a time, and early quantum attacks would be slow, expensive and selective. Attackers would likely target high-value wallets first. Many users who have never reused addresses and who avoid newer address formats that expose public keys on-chain already enjoy an additional layer of protection. Their public keys are revealed only at the moment they spend, creating a real-time race between the legitimate owner and a hypothetical quantum attacker.

The most vulnerable coins are those whose public keys are already exposed: early pay-to-public-key outputs, reused addresses, and certain newer address types. For abandoned coins in these categories, the problem becomes legal as well as technical. Allowing quantum attackers to seize them could trigger complex disputes under theft and computer-fraud laws, especially because inactivity does not prove that a rightful owner no longer exists.

Bitcoin’s low transaction throughput adds another layer of difficulty, Thaler writes. Even once a migration plan exists, moving all vulnerable funds could take months. These realities make it critical for Bitcoin to begin planning its post-quantum transition well before any cryptographically relevant quantum computer appears — not because the technology is imminent, but because the social and logistical machinery required to respond is slow.

He adds that Bitcoin’s proof-of-work security mechanism is not fundamentally broken by quantum computing. It relies on hashing, which at most sees a quadratic speed-up under known quantum algorithms. Practical constraints make even that speed-up unlikely to translate into decisive real-world advantages.

The Real Risks of Post-Quantum Cryptography

While the quantum threat to cryptography remains distant in most areas, the risks of post-quantum cryptography are immediate and tangible, according to Thaler. Modern post-quantum systems are built on a small number of mathematical foundations: hashing, error-correcting codes, lattices, multivariate quadratic equations and isogenies. Each approach trades performance for security assumptions in different ways.

Hash-based cryptography is the most conservative but also the least efficient. The digital signatures standardized by federal authorities under this approach are measured in kilobytes rather than bytes, making them roughly 100 times larger than today’s elliptic-curve signatures. Lattice-based schemes dominate current standardization efforts because they offer better performance, but they still impose substantial overhead and bring complex implementation challenges. Some of the most efficient lattice systems require delicate floating-point arithmetic that is notoriously difficult to secure against side-channel leaks.

Thaler says that implementation security, not quantum computing, is the dominant cryptographic risk for years to come. Post-quantum systems involve more complicated internal state, more opportunities for timing leaks and fault attacks, and broader attack surfaces. Several high-profile post-quantum candidates were broken using ordinary computers during the standardization process, underscoring how fragile new cryptographic designs can be even before quantum computing enters the picture.

For blockchains, these risks are compounded by the need for signature aggregation, which allows thousands of signatures to be combined efficiently. Today’s systems rely heavily on schemes that are not post-quantum secure. Research into post-quantum aggregation is advancing, often using zero-knowledge proofs as a bridge, but Thaler cautions that these techniques remain early and complex.

He warns that premature migration to post-quantum signatures could lock blockchains into suboptimal systems that later require another disruptive transition when better tools emerge or when vulnerabilities are discovered. Traditional internet infrastructure offers a sobering precedent: even after hash functions like MD5 and SHA-1 were fully broken, years passed before they were broadly removed from real-world systems.

What Should Happen Next

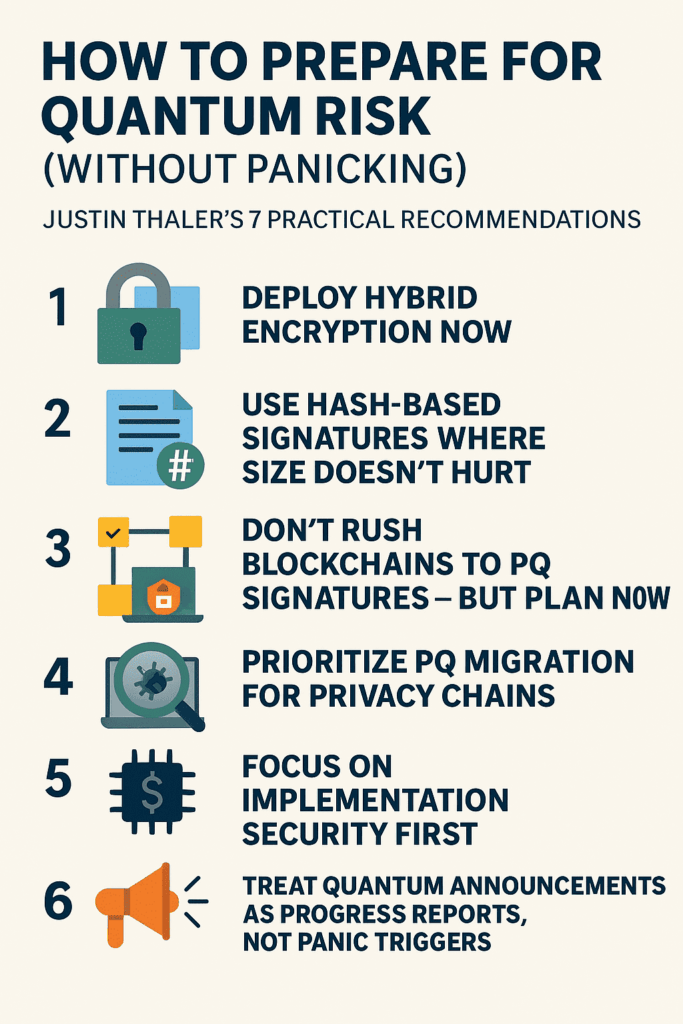

Thaler outlines a path forward that tries to balance urgency with restraint. Hybrid encryption should be deployed immediately wherever long-term confidentiality matters. Hybrid approaches hedge both against future quantum attacks and against the possibility that new post-quantum schemes prove weaker than expected.

Hash-based signatures, despite their size, should be adopted now in contexts where performance and bandwidth are not critical, such as software and firmware updates. Doing so avoids a dangerous bootstrapping problem in which future post-quantum updates could not be securely distributed after a quantum breakthrough.

For blockchains, Thaler warns against rushing post-quantum signatures into production but strongly in favor of planning now. Governance frameworks, migration paths and policies for abandoned funds must be debated and defined well in advance. Waiting until a quantum emergency would risk chaos.

Privacy-focused blockchains should move sooner, either through hybrid cryptography or architectural redesigns that eliminate long-term decryptable secrets. Across all systems, developers should prioritize code audits, formal verification, and protections against side-channel and fault-injection attacks. These threats are present now and have already caused real-world losses.

At the national level, Thaler emphasizes the importance of sustained funding for quantum computing itself. If a geopolitical rival achieved cryptographically relevant quantum capability first, the strategic implications would be severe. At the same time, he cautions policymakers and industry leaders to maintain perspective on quantum announcements.

Thaler says that frequent milestones are not signs of imminent danger but evidence of how many technical bridges remain to be crossed.

The blog post offers a deeper dive into technical aspects of the situation that this article may summarize. We recommend reading the post in its entirety.