Insider Brief

- A new study finds that university-based startups, including those in quantum, may underperform corporate-led startups because of a range of cultural, motivational and organizational challenges.

- Academic founders often struggle to transition from research-focused identities to market-driven leadership, limiting their ability to build scalable, customer-focused ventures.

- The study recommends actionable steps for university startups, including early market testing, embracing management routines, and forming complementary teams to bridge knowledge gaps.

University-based startups often begin with strong science, but a new study suggests they lag in execution — and that gap matters for commercial success, especially in fields like quantum technology.

The theoretical analysis, published in The Journal of Technology Transfer, finds that university startup entrepreneurs (USEs) consistently underperform their corporate counterparts (CSEs), despite institutional support and access to novel research. Drawing on a wide range of literature to explain why, the study argues that academic founders face unique cultural, motivational and organizational hurdles that limit startup performance, particularly in highly technical, emerging markets like quantum computing and quantum sensing.

“My analysis is part literature review, and part ‘appreciative theorizing,’ which comes from applying rigorous theoretical frameworks from previous literature,” said Alex Coad, author of the study and professor of the Waseda Business School, Waseda University, Japan, in a university news release.

The paper outlines key differences between USEs and CSEs that help explain why university spinoffs rarely dominate the tech landscape, even in science-driven fields. Among the most significant findings is the difficulty many academic founders have in switching from a research mindset to an entrepreneurial one. USEs are often motivated by scientific curiosity, peer recognition, and the pursuit of public good, while CSEs are more likely to be driven by financial outcomes and market validation.

That difference in mindset may be critical in shaping behavior, according to the study. University founders tend to focus on technical details and neglect commercial testing, often delaying engagement with users and customers. In contrast, corporate founders usually come from environments where market signals drive decision-making. They are more familiar with product-market fit, supply chains, and regulatory processes and they are more willing to build and scale pragmatically.

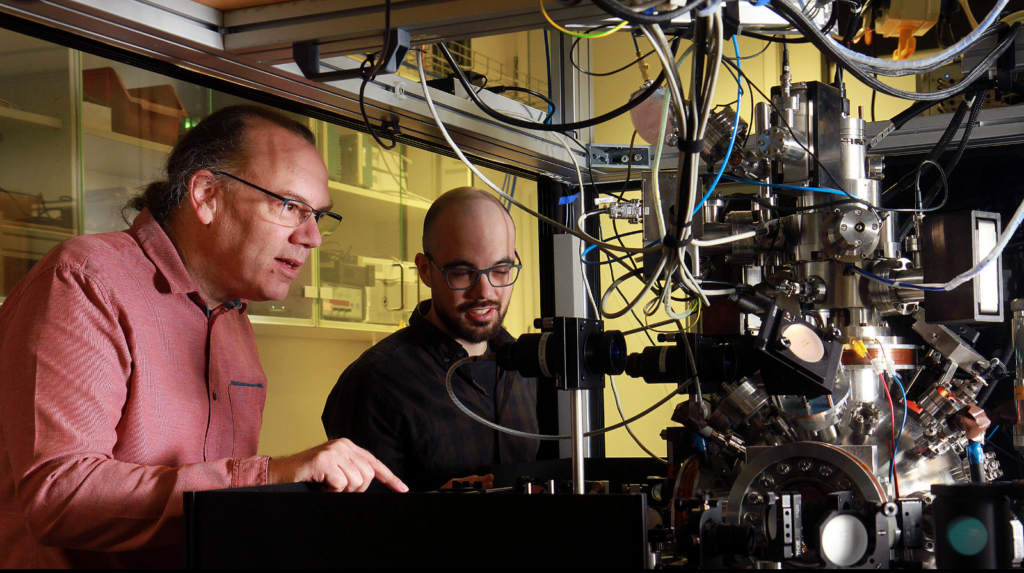

For quantum startups, which often emerge from university labs and depend heavily on basic research, the implications are direct. Teams may have strong intellectual property and technical depth, but miss the mark on usability, speed to market, and operational discipline.

Developing those missing pieces of CSE success might not be difficult for university startups, the researcher suggests. It may just be a matter of awareness and focus.

“In our view, testing prototypes on the market to find product-market fit is not ‘rocket science’ but is an early-stage activity that is within the grasp of USEs, if they are willing,” Coad writes in the study. “USEs may have a tendency to withdraw from commercialization activities and revert to focusing on technological problem-solving.”

Institutional Support Is Not Enough

USEs enjoy advantages that should position them for success. According to the study, they typically receive formal encouragement from their institutions, may retain access to patents and often can return to academia if the venture fails. In theory, these benefits reduce the risk of entrepreneurship and foster more opportunity-driven ventures.

But the data suggest otherwise. Empirical comparisons cited in the study show that university startups underperform on key metrics, including growth, survival, and successful exits. For example, USEs are less likely than CSEs to achieve liquidity events, such as acquisition or IPO. Other studies show that even when USEs have access to public funding or patents, they rarely convert those assets into high-growth companies.

Part of the problem is structural. Academic environments prioritize autonomy, publication, and long-term exploration. That culture clashes with the demands of early-stage startup life, which rewards short-term decision-making, continuous iteration, and customer responsiveness. USEs also often lack experience in navigating hierarchies, managing teams, or building commercial partnerships—skills more common among corporate founders.

Tips for Quantum Startups in Academic Settings

The study offers several takeaways that are particularly relevant for quantum startups, where high scientific barriers and long commercialization timelines amplify existing challenges. These recommendations aim to close the performance gap:

- Start with the customer, not the science.

Academic founders often prioritize the elegance or novelty of their technology. The study warns that this can delay commercial validation. Founders should actively test market demand using minimum viable products and direct user feedback. - Treat identity change as part of the job.

Shifting from a researcher to an entrepreneur involves more than learning new skills — it requires a different mindset. The study describes this as a “liminal process” and suggests that unresolved identity conflicts may lower startup performance. Founders should fully embrace their new roles rather than splitting time between lab work and business development. - Bring in complementary talent early.

Many knowledge gaps — such as supply chain management or regulatory navigation — stem from the academic founder’s limited exposure to commercial operations. Partnering with individuals who have corporate or entrepreneurial experience can fill these gaps and reduce costly mistakes. - Reframe repetitive tasks as value creation.

Administrative work, hiring, and performance reviews may feel mundane, but they are essential to scale. The study finds that USEs often resist these tasks due to cultural aversion or lack of experience, but successful startups must routinize execution. - Avoid undervaluing your contribution.

Academic inventors often play a foundational role in developing core IP, but because their upstream investment is already “paid for” by the university, they may lose leverage in negotiations with external partners. Founders should recognize and defend their value at the bargaining table.

How the Study Was Built

Rather than relying on a single dataset, the study synthesizes a broad literature base across economics, sociology, and management. It compares USEs and CSEs across seven dimensions: motivation, risk-aversion, identity formation, knowledge endowments, management style, collaboration dynamics, and performance outcomes. It draws on previous empirical studies from the U.S., U.K., Germany, and Scandinavia, and adds theoretical interpretations to explain consistent trends.

Among the most interesting frameworks is the distinction between “Communitarian” and “Darwinian” cultures. Academic founders are described as communitarian — focused on peer value and societal impact — while corporate founders operate in a more Darwinian fashion, emphasizing competition and profit. This cultural mismatch explains why many USEs struggle to thrive under the constraints of private markets.

The study also uses innovation models like the “linear model” of technology transfer and the “ultimatum game” to show how upstream scientific work can be undervalued in downstream commercialization. These frameworks provide cautionary lessons for founders seeking equitable returns from their intellectual contributions.

Limitations and Future Research

Coad notes that the study is a conceptual review rather than a controlled experiment. While it cites extensive data, it does not necessarily introduce new empirical findings. The study could be considered strongest as a synthesis and hypothesis-generating tool. The author encourages further research on identity transitions, time-use patterns and managerial capability comparisons between university and corporate entrepreneurs.

The study points the way toward more analysis on how deep tech sectors like quantum — where startups depend on decades of basic science — can build teams that bridge cultural and operational divides. It also suggests the need for better institutional mechanisms to support identity transformation and commercial capability development among academic founders.

While the study is not explicitly about quantum startups, or even deep tech ventures in general, entrepreneurs in those areas may be especially vulnerable to the pitfalls identified in the study. For these startup leaders, the main challenge could be learning the rules of the market without losing sight of the science.

Unlike software companies, which can pivot quickly and launch with low capital, quantum ventures also tend to require specialized infrastructure, long product cycles and intensive collaboration across academia and industry. The success of these companies, then, depends not only on breakthrough science but on the ability of founders to lead teams, attract capital and deliver value to customers.

Closing the gap between USEs and CSEs isn’t just about teaching scientists how to write business plans. It requires a structural and cultural shift, both at the level of the individual entrepreneur and the institutions that support them.

“Academics are often driven by curiosity and intellectual appeal, rather than profits,” writes Coad. “Hence, the transition from academic to entrepreneur is a long and difficult journey, involving more “identity work” than the transition from private sector employee to entrepreneur. Practical implications would be that academic entrepreneurs could be supported (e.g. with mentoring and peer support networks) in the development of a new commercialization-focused entrepreneurial identity.”