Insider Brief

- Two new studies show that moving the most time-consuming classical step in hybrid quantum algorithms onto GPUs can cut runtimes from hours to minutes, narrowing the gap between classical processing and quantum execution.

- The work focuses on sample-based quantum diagonalization, where classical diagonalization — not quantum sampling — has been the dominant bottleneck, and demonstrates that GPU-native and GPU-offloaded approaches can dramatically reduce that cost.

- The results suggest a shift in hybrid quantum computing toward GPUs as core infrastructure, while highlighting ongoing limits related to memory capacity, scalability requirements, and the continued need for close integration with high-performance classical systems.

Hybrid quantum computing has long promised to stretch the limits of what today’s early quantum machines can do. However, those efforts have repeatedly run into a stick problem, namely, that classical computers must process and refine quantum results that often take far longer to run than the quantum experiments themselves.

Now, two new studies from IBM researchers and their partners suggest that bottleneck is beginning to break.

The papers — GPU-Accelerated Selected Basis Diagonalization with Thrust for SQD-based Algorithms and Scaling Sample-Based Quantum Diagonalization on GPU-Accelerated Systems using OpenMP Offload — report large performance gains from moving the most demanding classical step in a widely used hybrid quantum algorithm onto modern graphics processors, cutting computation times from hours to minutes and bringing classical runtimes closer to the pace of quantum execution. The results from both stodies point to a shift in how hybrid quantum workloads are engineered, positioning GPUs as core infrastructure rather than optional accelerators.

The work is focused on sample-based quantum diagonalization, or SQD, a hybrid method used in quantum chemistry and materials science to calculate the energy states of complex molecules. SQD relies on a feedback loop: a quantum processor generates samples of possible electronic configurations, while a classical system filters those results and performs large-scale numerical calculations to refine the answer. That classical post-processing, not the quantum sampling, has emerged as the dominant cost.

The team’s new results show that redesigning this classical step for GPU-based supercomputers can dramatically reduce that cost, potentially expanding the range of chemical systems that can be studied with near-term quantum hardware.

A Classical Problem at the Heart of Quantum Algorithms

In SQD, the quantum processor’s role is limited but crucial. It samples from a quantum circuit that encodes information about a molecule’s electrons, producing candidate configurations that are likely to matter for the system’s lowest-energy states. Those configurations are then handed off to a classical computer, which builds a reduced mathematical model of the molecule and solves for its energies using an iterative method.

That classical step involves repeatedly applying a large mathematical operator, known as a Hamiltonian, to vectors representing electronic states. Even when the full operator is never explicitly stored, evaluating its effect can require billions of small calculations. As systems grow, this diagonalization step quickly dominates runtime.

Earlier large-scale SQD demonstrations relied on massive CPU-based supercomputers, including Japan’s Fugaku system, to handle this workload. While effective, those runs required extensive computing resources and long runtimes, limiting how frequently such calculations could be performed.

At the same time, the world’s fastest supercomputers have increasingly shifted toward GPU-accelerated designs. Systems such as Frontier and Aurora rely on thousands of GPUs to deliver their peak performance, leaving CPU-centric algorithms at a disadvantage unless they are reworked to fit that architecture.

IBM’s new studies tackle that mismatch directly.

Rebuilding Diagonalization for GPUs

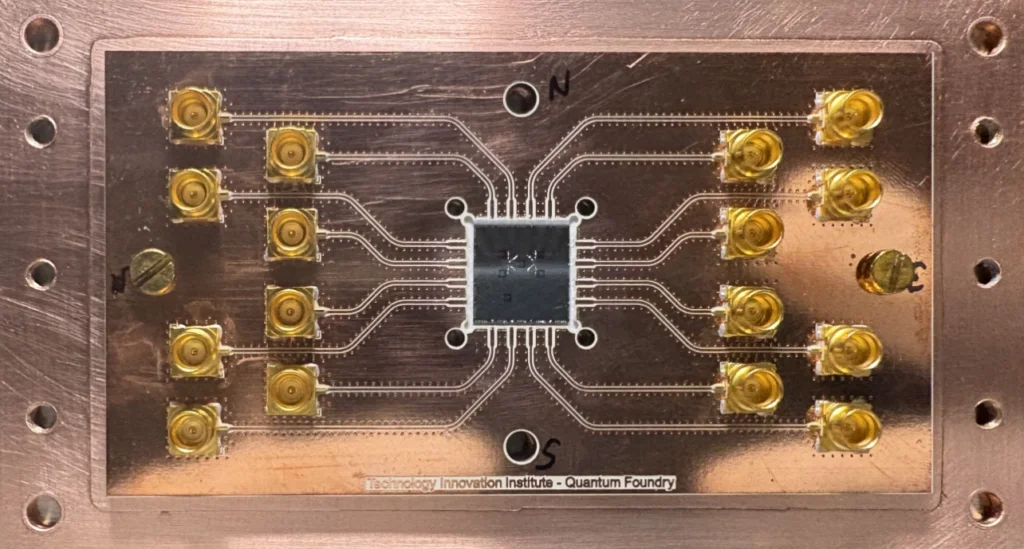

One of the studies, led by researchers at IBM Research in Tokyo in collaboration with Japan’s RIKEN research institute, focuses on a GPU-native redesign of the diagonalization step used in SQD. Instead of using software tools to automatically shift CPU code onto GPUs, the team rewrote the most demanding parts so the data and calculations are organized in a way GPUs can handle efficiently.

Diagonalization — a standard mathematical method used to determine a system’s energy states — is one of the core classical routines in SQD. The researchers reorganized how electronic configurations are stored in memory, flattened nested data structures and restructured loops to expose fine-grained parallelism suitable for thousands of GPU threads. The implementation uses standard GPU programming libraries to manage memory and parallel execution while keeping data resident on the device.

In tests on modern GPU clusters, the approach delivered speedups of up to roughly 40 times compared with CPU execution for the diagonalization step. The gains came primarily from exploiting the massive number of concurrent threads available on GPUs, even though the underlying calculations involve relatively little floating-point math and are dominated by integer operations and data movement.

The study also emphasized portability. While designed for Nvidia GPUs, the underlying techniques can be adapted to other architectures with modest changes, an important consideration as high-performance computing systems diversify.

By focusing on the classical bottleneck rather than the quantum hardware itself, the work reframes where progress in near-term quantum computing can come from. Faster classical processing allows quantum experiments to iterate more quickly and tackle larger problems without waiting on prohibitively long post-processing steps.

Scaling Across Exascale Systems

A second study, led by IBM Research in the United States with collaborators from Advanced Micro Devices and Oak Ridge National Laboratory, examines the same diagonalization challenge from a different angle: how to scale it efficiently and portably across full exascale systems.

Rather than rewriting the algorithm from scratch, the team used modern OpenMP — a programming standard for running calculations in parallel — offload techniques to move the most computationally intensive portion of SQD onto GPUs while keeping the broader codebase intact. The goal was to maintain a single code base that could run efficiently on both CPU-only and GPU-accelerated systems.

The researchers focused on matrix-vector multiplication — the step where large tables of numbers are repeatedly applied to long lists of values — which accounts for most of the time spent in each diagonalization cycle. By reorganizing how data is stored, keeping frequently used information on the GPU, and moving this core calculation there, they achieved large performance gains without rewriting the entire algorithm.

Benchmarks on the Frontier supercomputer at Oak Ridge showed speedups of roughly 95 times per node compared with the original CPU implementation, reducing diagonalization times from hours to minutes for representative molecular systems. Tests across other GPU platforms, including newer AMD and NVIDIA hardware, showed additional gains as GPU architectures evolved.

Importantly, the study demonstrated that these improvements scaled to hundreds or thousands of GPUs with high efficiency. Communication overhead remained a relatively small fraction of total runtime, indicating that the approach could support even larger calculations as system sizes grow.

According to the researchers, ultimately, the results suggest that GPU-accelerated diagonalization is not just a laboratory optimization but a practical path for running hybrid quantum algorithms at scale on today’s largest machines.

Why Speedups Matter for Quantum Computing

While recognizing the improved performance is important, the real significance of the studies may lie in what these new methods can enable.

Hybrid algorithms like SQD are designed to work within the limits of current quantum hardware, which remains noisy and relatively small. Their value depends on running many iterations, refining results as quantum samples and classical calculations inform each other. If the classical side is slow, that feedback loop stalls.

By shrinking classical runtimes to match or even undercut quantum execution times, the new approaches make it feasible to run more iterations, explore larger configuration spaces, and study more complex molecules. That could expand the practical reach of quantum chemistry applications in areas such as catalysis, materials design, and energy research.

The work also underscores a broader trend in quantum computing: progress increasingly depends on integration with high-performance classical systems rather than standalone quantum advances. As quantum processors improve incrementally, gains from better classical algorithms and infrastructure can have an outsized impact on what users can accomplish.

At the same time, the studies highlight remaining constraints. GPU memory limits still cap the size of problems that can be handled efficiently, and the methods rely on having enough parallel work to keep thousands of GPU threads busy. Smaller systems may still run more effectively on CPUs.

Both of these studies are complex. For a deeper, more technical dive, beyond the scope of this article, please review the papers — GPU-Accelerated Selected Basis Diagonalization with Thrust for SQD-based Algorithms and Scaling Sample-Based Quantum Diagonalization on GPU-Accelerated Systems using OpenMP Offload –on arXiv. It’s important to note that arXiv is a pre-print server, which allows researchers to receive quick feedback on their work. However, it is not — nor is this article, itself — official peer-review publications. Peer-review is an important step in the scientific process to verify results.