Insider Brief

- A new PRX Quantum study finds that near-term, small-scale quantum processors could significantly improve exoplanet detection by processing faint starlight before measurement, reducing noise and required photon counts.

- The researchers show that quantum signal processing can separate planetary light from stellar glare without full image reconstruction, cutting the number of detected photons needed by several orders of magnitude under realistic conditions.

- While the approach remains theoretical and faces engineering challenges, the study outlines a plausible hybrid hardware path that could integrate quantum processors directly into future astronomical instruments.

Scientists might be able to take quantum computers to the stars… and beyond.

A new study suggests that small quantum computers could dramatically sharpen astronomers’ ability to detect distant exoplanets by extracting usable information from light that is otherwise lost in noise.

The research, published in PRX Quantum, shows that quantum information processing can be used not to simulate planets or analyze astronomical data after the fact, but to process faint starlight before it is measured, reducing the number of detected photons required to identify a planet by several orders of magnitude. If realized, the approach could shorten observation times, ease stability requirements for telescopes and expand the range of planetary systems that can be studied.

The work focuses on separating the dim signal of an exoplanet from the overwhelming glare of its host star, one of astronomy’s most stubborn challenges. Even with modern instruments — such coronagraphs and starshades — that suppress starlight, astronomers typically rely on long integrations and extensive classical post-processing to tease out a planetary signal. That process is limited by shot noise, the random fluctuations that arise when photons are detected one by one.

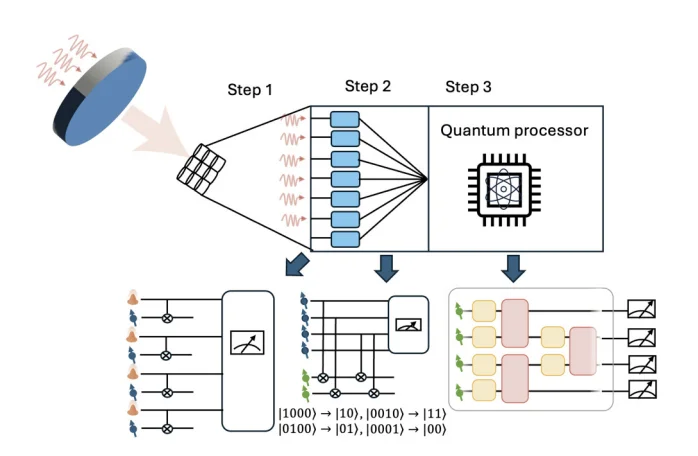

According to the study, conducted by researchers from Eindhoven University of Technology, NASA Goddard Space Flight Center and Harvard University, quantum processors offer a fundamentally different way to approach the problem. Instead of detecting light at each pixel and then trying to reconstruct an image using classical algorithms, the proposed method converts the incoming light itself into a quantum state and processes it coherently before measurement. The result is a more efficient way to isolate the planet’s contribution without first reconstructing the full image of the star and its surroundings.

The researchers report that, under realistic imaging conditions, their approach could reduce the number of detected photons needed to achieve a given signal-to-noise ratio by three to four orders of magnitude compared with standard tomographic methods. In practical terms, that could mean detecting a planet in hours rather than weeks, or making viable observations that are currently out of reach.

Quantum Processing Before Detection

At the center of the proposal is a shift in where computation happens in the imaging chain. In conventional optical imaging, a telescope collects light and a detector records the intensity at each pixel. All further analysis happens after detection, using classical computers that work with noisy measurement results.

The study instead imagines replacing conventional pixels with quantum-enabled detectors that can map the amplitude of an incoming photon into a set of qubits. In this scheme, each photon that arrives at the detector is stored as a quantum state spread across many modes, preserving information about how the light interferes across the image.

Once stored, those quantum states can be processed using quantum algorithms before any measurement is made. The researchers describe a sequence of operations that effectively sorts the incoming light into modes associated with different physical sources, such as a star and a nearby planet. By measuring the processed state, astronomers could directly estimate properties of the planet without first reconstructing the full optical field.

The key advantage, according to the study, is that this approach avoids tomography, the process of reconstructing a full image or density matrix from many measurements. Tomography scales poorly as images become larger and noisier, because errors accumulate across all pixels. Quantum processing, by contrast, can extract specific features of interest directly, allowing noise to enter only at the final measurement step.

The paper applies this idea to a simplified but representative model of exoplanet imaging, in which light from a star and a planet arrives as a mixture of weak single-photon signals. By using quantum algorithms related to principal component analysis and signal processing, the method separates these contributions even when the star remains significantly brighter at the detector.

Implications for Astronomy

The work could have several implications for observational astronomy, including a significant cut in the time it takes to conduct an exoplanet study. Many proposed exoplanet missions are constrained not by telescope size but by how long they must stare at a target to build up enough signal. Reducing the photon budget could free up observing time and allow surveys to cover more stars.

The technique could improve stability, the study suggests. Long integrations place strict demands on the mechanical and thermal stability of telescopes, especially in space. Shorter observation times could relax those requirements, potentially lowering mission costs or enabling new designs.

The approach could also support narrower-band measurements. Detecting atmospheric molecules linked to habitability often requires isolating light in specific spectral lines. For example, targeting oxygen, methane, or water vapor absorption features appear only at narrow wavelengths when a planet passes in front of its star. Narrow filters reduce photon counts, making measurements difficult with classical techniques. The quantum-enhanced method is particularly well suited to such low-flux regimes, the researchers report.

More broadly, the work points to a role for quantum computers as part of scientific instruments, rather than as standalone machines used only for abstract computation. In this view, quantum processors would sit alongside optics and detectors, performing specialized processing tasks that classical hardware handles inefficiently.

How Realistic is the Hardware?

The study emphasizes that the proposed advantage does not depend on large, fault-tolerant quantum computers. The team estimates that imaging a system resolved on a 10-by-10 pixel array would require on the order of 36 memory qubits and a few hundred two-qubit gates. Those figures are modest by the standards of quantum computing research.

The paper outlines a hybrid architecture in which light is first captured by quantum-enabled pixels based on solid-state defects in diamond, then transferred to a separate quantum processor, such as an array of neutral atoms, for further processing. Many of these components, including photon-to-qubit interfaces and small atomic processors, have already been demonstrated in laboratory settings, according to the study.

However, the researchers are careful to note that integrating these components into a functioning astronomical instrument would be a major engineering challenge. Losses in optical coupling, imperfect gate operations and environmental noise would all reduce the achievable gains. The study includes a conservative noise model and finds that, even with realistic imperfections, quantum processing could still offer substantial reductions in sampling complexity compared with classical methods.

The analysis also assumes that certain parameters, such as the relative brightness of the star and planet after starlight suppression, are known or can be estimated. In practice, uncertainties in these values would need to be managed, potentially requiring additional calibration measurements.

It’s important to note that the work is theoretical and no quantum-enhanced telescope has yet been built. The imaging scenario considered involves two unresolved sources, a star and a single planet and extending the method to more complex systems would require additional development. Sorting light from multiple planets or from structured backgrounds could be more challenging, especially if their signals overlap strongly.

There are also practical questions about scaling. While the study shows that the number of required qubits grows only logarithmically with image size after compression, the initial mapping from optical modes to quantum memory still involves many physical channels. Implementing such systems outside the laboratory would require advances in photonic integration and robust quantum interfaces.

With all this in mind, the study identifies a concrete application where quantum information processing could outperform classical techniques without waiting for future breakthroughs in error correction or large-scale quantum hardware. By focusing on measurement efficiency rather than computational speed, it reframes the conversation about where quantum advantage might first appear.

In the near term, the team suggest that proof-of-principle experiments could be performed in controlled settings, using weak optical signals and small detector arrays to demonstrate the predicted signal-to-noise improvements. Such experiments would help determine how much of the theoretical advantage survives real-world imperfections.

Looking at this longer term for astronomy, this study yet another idea on a growing list that shows how quantum technologies may not replace existing tools, but could extend or enhance classical tools and methods. If quantum processors can indeed help telescopes see fainter worlds with fewer photons, they could become an unexpected ally in the search for planets beyond the solar system.

The research team included Aleksandr Mokeev, of Eindhoven University of Technology in the Netherlands, Babak Saif, of NASA Goddard Space Flight Center in Greenbelt, Maryland, and Mikhail D. Lukin and Johannes Borregaard, both of Harvard University.