Insider Brief

- Researchers, including scientists from IBM and Algorithmiq, showed that a 91-qubit quantum processor, using error mitigation rather than full error correction, can reliably simulate strongly chaotic many-body quantum dynamics.

- The study validated results against exact theory where available and used error-mitigated quantum data to resolve disagreements between competing classical simulation methods.

- The work suggests that near-term quantum computers can serve as trustworthy tools for studying complex physical systems and benchmarking hardware performance before fault-tolerant machines are available.

- Photo by Daniele Levis Pelusi on Unsplash

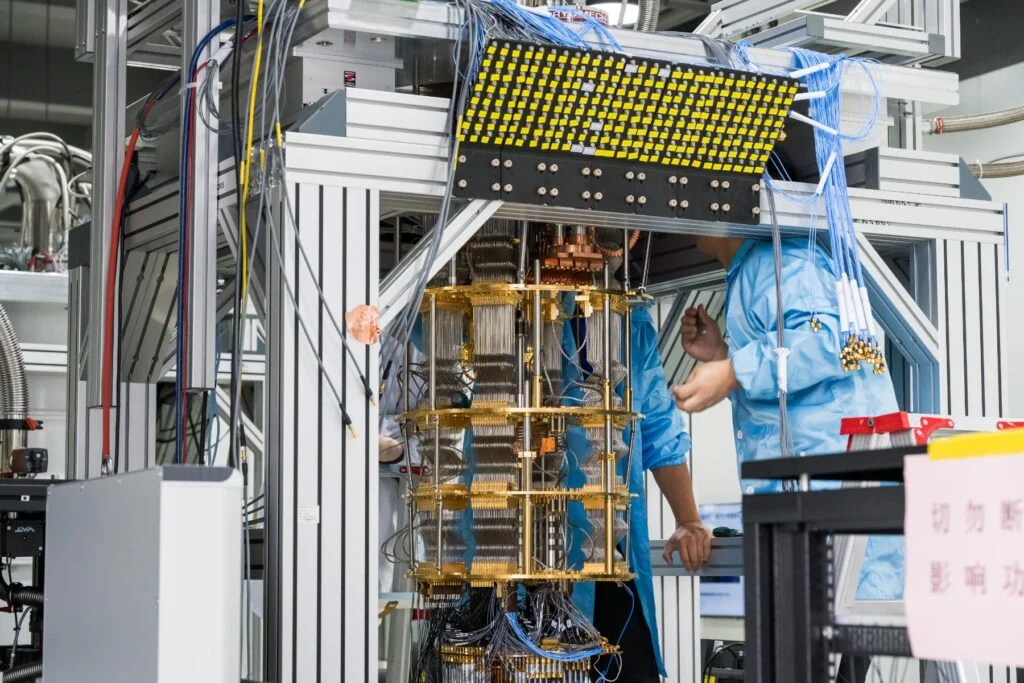

A 91-qubit quantum processor — relying on error-mitigation techniques rather than full error correction — accurately reproduced the telltale signatures of quantum chaos. Reproducing chaos may not sound like a great result, but it showed that today’s machines may be able to reliably study complex many-body physics before fault-tolerant quantum computers arrive.

Beyond benchmarking quantum computers, these tools could eventually improve understanding of how large collections of interacting parts behave — and could one day find their way into advancing materials science, making drug discovery more efficient and even solving complex everyday planning problems such as traffic flow and logistics.

According to the study published in Nature Physics, the researchers used a superconducting quantum computer from IBM to simulate highly chaotic quantum dynamics at a scale that strains classical verification. By combining carefully chosen quantum circuits with advanced post-processing techniques, the team, which included researchers from IBM Quantum, Algorithmiq Ltd and Trinity College Dublin, was able to recover results that match exact theoretical predictions and, in harder cases, help adjudicate between competing classical simulations.

The work addresses how to trust results from noisy hardware when the problems being studied are too large or too chaotic to check exactly on a classical computer. This is a persistent credibility problem for near-term quantum computing. According to the study, the solution lies in pairing hardware experiments with models that are analytically solvable in specific limits and with error-mitigation methods that correct noise, in this case, after the computation has run.

The experiments focused on what are called dual-unitary circuits, a special class of quantum circuits that are maximally chaotic yet unusually easy to work with. In ordinary quantum systems, chaos causes information to spread rapidly across many interacting particles, making precise calculations extremely difficult. Dual-unitary circuits are unusual because they mix information extremely fast, yet still allow exact predictions for a few carefully chosen measurements.

The researchers implemented these circuits on a superconducting quantum processor with up to 91 qubits, executing more than 4,000 two-qubit gates. They measured how information propagated through the system following a sudden disturbance, tracking a quantity known as an infinite-temperature autocorrelation function. In simple terms, it shows how quickly a small signal fades as the system changes over time.

According to the study, the unprocessed experimental data decayed much faster than theory predicted, a clear signature of hardware noise. After applying tensor-network error mitigation — as mentioned, a classical post-processing technique that attempts to mathematically undo the effect of noise — the measured decay closely followed the exact theoretical curve. This agreement held across several system sizes, from 51 to 91 qubits and across parameter regimes where the underlying model shifts from integrable to strongly chaotic.

The result demonstrates that error mitigation can work even in non-Clifford circuits, which involve more general quantum operations and are considered more representative of real scientific workloads than simplified benchmark circuits.

Implications for Near-Term Quantum Computing

The study adds to a growing body of evidence that useful quantum simulations may be possible without waiting for full quantum error correction, which requires large overheads in qubits and control. Instead of eliminating errors at the hardware level, error mitigation accepts noisy results and corrects them statistically after the fact, trading increased classical computation for reduced quantum demands.

In this case, the researchers report that the entire workflow for the largest experiments — including noise characterization, mitigation and data collection — took just over three hours. Sampling rates exceeded 1,000 measurements per second, a substantial improvement over earlier large-scale experiments that relied on similar mitigation ideas.

Beyond raw performance, the work proposes dual-unitary circuits as a practical benchmark for pre-fault-tolerant quantum computers. Clifford circuits, which can be efficiently simulated classically, are commonly used for testing hardware but do not capture the complexity of many real applications. Fully generic chaotic circuits, by contrast, are difficult to verify. Dual-unitary circuits occupy a middle ground in that they are complex enough to stress hardware and mitigation methods, yet constrained enough to allow analytical checks.

After validating their approach at points where exact solutions exist, the researchers pushed the system into regimes where no closed-form answers are known. They deliberately perturbed the circuit parameters away from the dual-unitary point and measured local observables at late times.

At this scale, brute-force classical simulation is impossible, so the team compared their quantum results with approximate tensor-network simulations performed by tracking the evolution of quantum states or tracking the evolution of operators. The two classical methods disagreed with each other, even when run at high numerical accuracy.

The error-mitigated quantum data aligned more closely with the operator-based classical simulations. According to the study, this suggests that quantum hardware — when combined with mitigation — can serve as an independent reference in situations where classical methods give conflicting answers. Rather than simply matching classical results, the quantum processor provided evidence about which approximation was more reliable.

This role, as an arbiter rather than a challenger, marks a subtle but important shift in how near-term quantum machines may be used. Instead of seeking outright computational advantage, they can complement classical tools in hard-to-simulate regimes of physics.

How it Works

The technical core of the approach is tensor-network error mitigation, or TEM. The method begins by learning a detailed noise model of the quantum hardware, focusing on the errors introduced by layers of two-qubit gates. These errors are represented mathematically as combinations of simple operations, allowing them to be inverted approximately.

Rather than altering the quantum circuit itself, TEM modifies the observable being measured. The noisy quantum computer runs the original circuit, while a classical tensor-network calculation reconstructs what observable would have produced the ideal, noise-free expectation value. Informationally complete measurements — randomly changing the measurement basis across runs — allow the corrected observable to be estimated from the noisy data.

The team emphasizes that TEM does not eliminate all sources of error. Its accuracy depends on how well the noise is modeled and how effectively the tensor-network approximations capture the relevant correlations. As circuit depth increases, small model inaccuracies can accumulate, leading to residual bias.

Limits and Next Steps

The researchers report there are limitations in their work and places where more work is needed. For example, the observables examined were chosen because they are particularly well suited to dual-unitary circuits and light-cone-like information flow. Other quantities, such as more general correlation functions or entanglement measures, may behave differently and could require substantially more sampling.

The researchers also report that error mitigation cannot replace fault tolerance. Its effectiveness ultimately depends on hardware stability and noise rates and it may break down as circuits become deeper or less structured.

Still, the work points to several near-term directions. Dual-unitary circuits could be used to study transport, localization and thermalization in driven quantum systems. Similar techniques could benchmark other platforms, such as trapped ions or neutral atoms. As hardware improves, the combination of mitigation and analytical structure may allow quantum simulations to surpass classical methods in specific areas of many-body physics.

The team included researchers from IBM Quantum, including Laurin E. Fischer, Francesco Tacchino, and Ivano Tavernelli at IBM Research Europe – Zurich, alongside Andrew Eddins at IBM Research – Cambridge, Nathan Keenan at IBM Research Europe – Dublin, and Youngseok Kim, Andre He, and Abhinav Kandala at the IBM T.J. Watson Research Center. Researchers from Algorithmiq Ltd included Matea Leahy, Davide Ferracin, Matteo A. C. Rossi, Francesca Pietracaprina, Boris Sokolov, Zoltán Zimborás, Sabrina Maniscalco, John Goold, Guillermo García-Pérez, and Sergey N. Filippov, who led the development of the tensor-network error mitigation framework and classical benchmarking. Additional theoretical contributions came from Trinity College Dublin, where Matea Leahy, Nathan Keenan, Shane Dooley, and John Goold are based, with further affiliation through the Trinity Quantum Alliance. Supporting academic affiliations included the University of Helsinki and its QTF Centre of Excellence, the Università degli Studi di Milano, and the HUN-REN Wigner Research Centre for Physics.