Insider Brief

- An IEEE study finds that today’s cloud-based quantum computers could face significant security risks, including manipulation, intellectual property theft and silent degradation of results, well before fault-tolerant machines arrive.

- The researchers show that quantum circuits, compilers, calibration processes and shared hardware can leak sensitive problem information or be exploited to inject errors in ways that are difficult or impossible to detect.

- The study concludes that without security-by-design in quantum hardware, software and cloud scheduling, growing commercial and government use of quantum computing could be undermined by untrusted or unverifiable results.

Quantum computers may be far more vulnerable to manipulation, theft and silent sabotage than their builders and users currently assume, according to a new IEEE study that indicates security risks are already embedded deep inside today’s hardware, software, and cloud-based quantum systems.

The paper, authored by researchers at Penn State, finds that many of the same features that make near-term quantum computers useful also make them uniquely exposed to attack. These include shared cloud access, heavy reliance on third-party tools, constant calibration and the fact that quantum programs often reveal sensitive problem details through their structure rather than through data alone. Taken together, the researchers warn, these weaknesses could allow attackers to degrade results, steal intellectual property, or subtly influence outcomes without leaving clear forensic evidence.

“Classical security methods cannot be used because quantum systems behave fundamentally differently from traditional computers, so we believe companies are largely unprepared to address these security faults,” said Swaroop Ghosh, professor of computer science and of electrical engineering at the Penn State School of Electrical Engineering and Computer Science, in a Q&A about the work. “Currently, commercial quantum providers are focused on ensuring their systems work reliably and effectively. While optimization can indirectly address some security vulnerabilities, the assets unique to quantum computing, such as circuit topology, encoded data or hardware coded intellectual property systems generally lack end-to-end protection.”

A Sign of Quantum’s Emergence?

The study arrives as quantum computing is beginning to move from laboratory demonstrations to early commercial use. Major technology companies now offer cloud access to real quantum hardware and governments and businesses are beginning to test quantum systems for optimization, chemistry, finance and machine learning. The team reports in the paper that security thinking has not kept pace with that shift.

One issue is just the novelty of quantum computing. Unlike classical computers, where cybersecurity practices are mature and layered, quantum systems have largely been designed with performance and reliability in mind, not adversarial threat models. The result is a growing gap between what quantum computers can do and how safely they can be deployed.

The researchers report that quantum security is not a future problem waiting for fault-tolerant machines. Many of the most serious risks apply directly to today’s noisy intermediate-scale quantum systems, or NISQ devices, which already operate through cloud platforms and shared hardware.

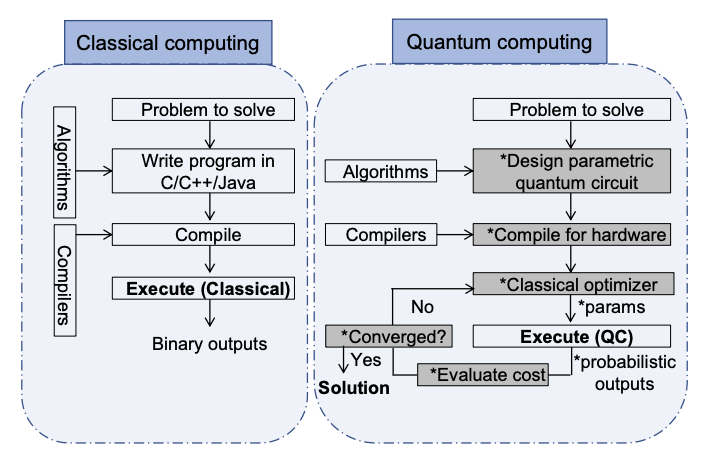

One central finding is that quantum circuits often encode valuable information directly into their structure. In classical computing, algorithms are usually generic, while sensitive details reside in input data. In quantum computing, especially for optimization and machine learning, the circuit itself can reveal the size of a problem, its constraints and even relationships among variables.

For example, variational algorithms such as the Quantum Approximate Optimization Algorithm and the Variational Quantum Eigensolver use problem-specific circuits whose patterns of connections and parameters reflect the underlying task. According to the study, access to those circuits could allow an observer to infer details about a portfolio optimization, a power grid layout, or a proprietary model without ever seeing the original data.

That creates a new kind of intellectual property risk. Quantum programs may be valuable assets even before they produce useful results, yet current platforms offer limited protection against copying, reverse engineering, or tampering.

The study also highlights risks introduced by untrusted compilation tools. Quantum programs must be compiled and optimized for specific hardware, a process far more delicate than classical compilation. Small changes in gate order, timing, or qubit placement can mean the difference between a usable result and random noise.

That means that researchers and companies are increasingly turning to third-party compilers that promise faster or better optimization than those provided by hardware vendors. The paper warns that these tools could be used to insert hidden changes, degrade performance, or extract proprietary information, often without detection. Traditional testing methods are ineffective because quantum outputs are probabilistic and often impossible to verify classically.

New Attack Pathways

Cloud-based access is another major focus of the study. Because quantum computers are expensive and scarce, providers often run multiple users’ programs on the same machine. This multi-tenant model is economically attractive, but it creates opportunities for interference that do not exist in classical systems.

Quantum bits are sensitive to their physical environment. Crosstalk between qubits can cause operations on one program to affect another, even if they are logically separate. The study describes how an adversarial program could exploit this behavior to inject faults into a neighboring computation, slow its convergence, or distort its output.

In superconducting systems, attackers could force additional swap operations, which move quantum information between qubits and increase error rates. In trapped-ion systems, they could trigger excessive shuttling of ions between traps, raising energy levels and reducing gate fidelity for other users. These effects would appear as ordinary noise or hardware variability, making malicious activity hard to distinguish from normal system behavior.

The researchers note that such attacks do not require privileged access. An attacker may only need the ability to submit jobs to the same machine and knowledge of publicly available hardware layouts.

Hardware and Aalibration Vulnerabilities

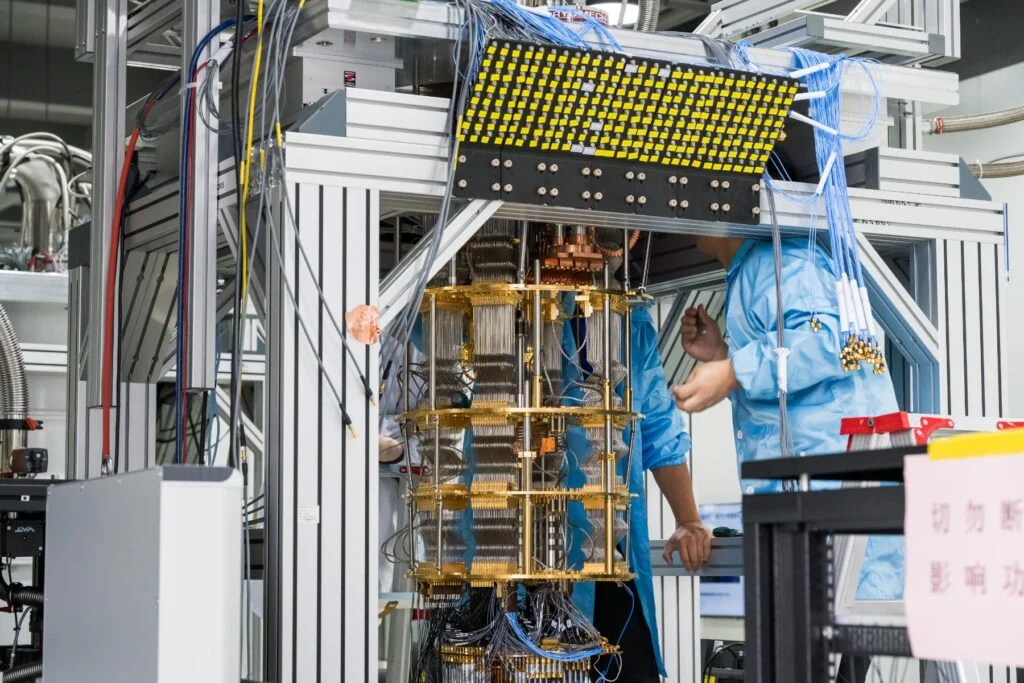

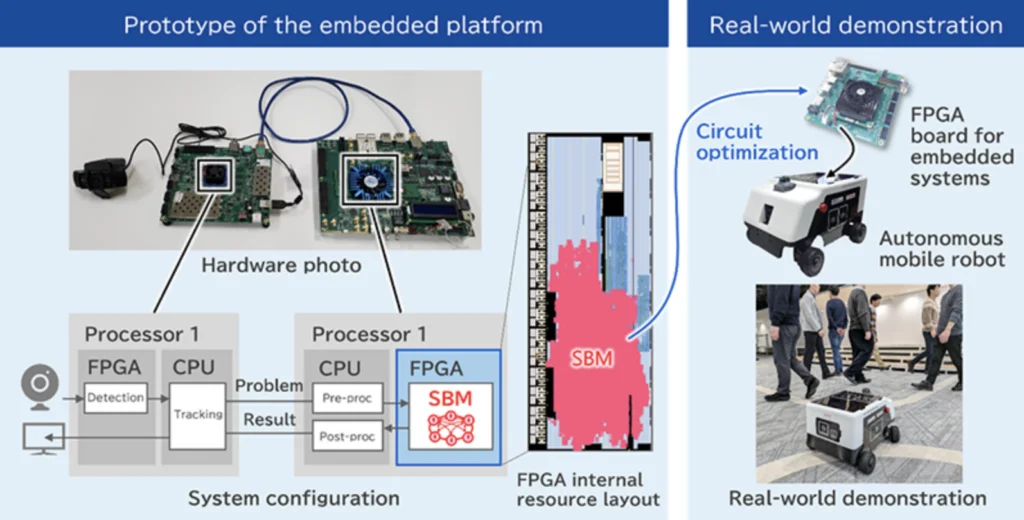

The study also points to risks at the hardware and control level. Quantum devices rely on precise analog control signals, often generated by classical electronics such as field-programmable gate arrays. Small disturbances in these signals can have outsized effects on quantum operations.

The researchers describe how faults in control electronics, whether accidental or induced, can alter gate amplitudes and phases, leading to large deviations in output distributions. Because quantum gates are continuous rather than discrete, even minor perturbations can significantly affect results.

Calibration is another weak point. Quantum hardware requires frequent tuning to compensate for drift and noise. If calibration services are compromised or misreported, users may unknowingly run programs on degraded hardware or receive manipulated error metrics. According to the study, there are few reliable ways for users to verify that calibration has been performed correctly or honestly.

These issues are compounded by hardware variability. Not all qubits are created equal and differences in coherence time and error rates can influence outcomes. Without transparency in scheduling and resource allocation, a user may be assigned inferior qubits while believing they are receiving optimal hardware.

A key conclusions is that quantum results are often impossible to verify after the fact. For many quantum problems, there is no efficient classical way to check whether an answer is correct. That makes subtle attacks especially dangerous.

A hacker does not need to fully corrupt a computation. Biasing probability distributions, slowing convergence, or nudging results toward suboptimal solutions may be enough to influence decisions in finance, logistics, or infrastructure planning. Because noise is already expected, these effects may go unnoticed.

This verification gap marks a fundamental difference from classical security, where redundancy, checksums and recomputation can often expose tampering.

Industry Implications, Policy Recommendations

The researchers said that these findings have immediate implications for quantum vendors, cloud providers and users. Security cannot be treated as an add-on or postponed until fault-tolerant machines arrive. Instead, it must be integrated into hardware design, compilation workflows and cloud orchestration.

“Quantum computers need to be safeguarded from ground up,” Ghosh said in the article. “At the device level, developers should focus on mitigating crosstalk and other sources of noise — external interference — that may leak information or impede effective information transfer. At the circuit level, techniques like scrambling and information encoding must be used to protect the data built into the system. At the system level, hardware needs to be compartmentalized by dividing business data into different groups, granting users specific access based on their roles and adding a layer of protection to the information. New software techniques and extensions need to be developed to detect and fortify quantum programs against security threats.”

The team also calls for new validation techniques that account for quantum noise and probabilistic outputs, as well as clearer trust boundaries for compilers and calibration services. They also suggest that scheduling policies in shared systems should explicitly consider security, not just performance and utilization.

For policymakers and funding agencies, the study raises questions about national security and economic competitiveness. Quantum systems are increasingly being explored for sensitive applications. Weak security could undermine trust in results or expose strategic intellectual property.

Limitations and Future Directions

It’s important to note that the paper is a broad survey rather than an experimental demonstration of a single exploit. Many of the attack models it describes have been shown in limited experiments or simulations, but not all have been observed in large-scale commercial systems. The team acknowledges that some attacks may be difficult to execute in practice due to vendor safeguards or operational constraints.

Still, they argue that the absence of evidence is not evidence of safety. Many vulnerabilities stem from fundamental physical and architectural properties that will persist as systems scale.

The study concludes by calling for a dedicated quantum security research community. This includes developing threat models specific to quantum hardware, creating benchmarks for secure compilation and designing hardware with isolation and monitoring features from the outset.

The researchers also suggest that some classical security concepts may need to be rethought rather than reused. Quantum mechanics introduces behaviors that do not map cleanly onto digital systems and defending against attacks may require new tools grounded in physics as much as computer science.

“Our hope is that this paper will introduce researchers with expertise in mathematics, computer science, engineering and physics to the topic of quantum security so they can effectively contribute to this growing field,” Ghosh concludes in the article.

Because the IEEE paper is paywalled, the arXiv version of the study was used for this article.

Suryansh Upadhyay and Abdullah Ash Saki, both of Penn State, worked with Ghosh.