Insider Brief

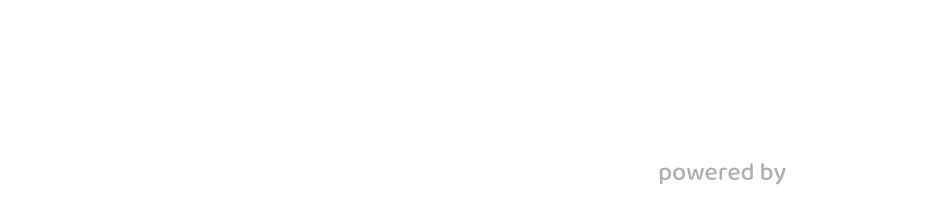

- A new study warns that restrictive quantum technology policies are entrenching global inequality by excluding the Global South from access to emerging quantum innovations.

- Export controls by the U.S., EU and China are limiting access to quantum hardware and communications tools, undermining research capacity and infrastructure development in poorer nations.

- The authors suggest the absence of a cooperative global framework could leave the Global South more vulnerable to security threats and deepen digital dependency.

Countries in the Global South risk being left out of the quantum revolution — along with its economic, technological and security benefits — due to growing export controls, siloed research initiatives and national security concerns, a new policy analysis argues.

In the first of a series of articles on quantum technologies published by the policy journal Just Security, researchers Michael Karanicolas, of Dalhousie University, and Alessia Zornetta, of UCLA Law, examine how the geopolitics of emerging quantum technologies are replicating long-standing patterns of technological exclusion. The authors argue that absent meaningful interventions, quantum could become another engine of global inequality, one that threatens to lock poorer nations out of the next era of technological and economic development.

Export Controls and Gatekeeping

The authors trace the roots of this divide to export control regimes that are quickly expanding in response to the strategic potential of quantum systems. Since 2020, governments in the U.S., EU and China have implemented targeted restrictions on quantum-enabling hardware, software, and communications systems.

The United States began tightening its grip in 2021 by banning exports to eight Chinese quantum companies, before rolling out broader licensing requirements in late 2024 that affect full quantum systems. The European Union’s restrictions, implemented through a dual-use framework, limit exports of systems that surpass 34 qubits—effectively capping access to devices that could perform meaningful quantum calculations. China, too, has clamped down, adding quantum encryption and ultra-low temperature components to its list of protected exports.

Karanicolas and Zornetta argue that while these restrictions are typically justified on national security grounds — particularly as a means to slow China’s progress — they inadvertently harm the Global South, which lacks the capital and research capacity to build these technologies domestically. As a result, many nations are excluded not only from developing their own systems, but also from deploying the quantum technologies that are expected to underpin next-generation security, communications, and healthcare infrastructures.

“These technology controls create concentric circles of access; allies enjoy privileged exchange while competitors face increasing challenges in establishing domestic quantum research programs,” the researchers write. “Though these controls are often justified as a means to constrain rivals—particularly China—they also have the unintended effect of locking out researchers and institutions from the Global South.”

The authors added that favored allies enjoying exchange privileges and others facing barriers to entry. That structure mirrors the Cold War-era technology blocs and undermines any notion of a globally shared quantum future.

Collaboration Carveouts — and Their Limits

Even as technology controls tighten, the report notes that some flexibility has emerged in research collaboration. Faced with talent shortages and international interdependence, leading quantum countries have made exceptions for knowledge-sharing.

Roughly half of the quantum professionals working in the United States are foreign nationals. Many U.S.-authored quantum research papers include international co-authors. The government has responded by allowing collaboration with these individuals—provided institutions keep detailed records.

The EU has shifted its stance as well, softening initial restrictions that limited research funding to member states. Cooperation agreements are now in place with the U.K., and further talks are underway with Switzerland.

By contrast, China is charting a more insular path, focused on developing a self-sufficient quantum workforce and cutting back on foreign partnerships. This divergence in strategies — collaborative openness in the U.S. and EU, inward consolidation in China — highlights a critical policy tension: balancing strategic control with global scientific progress.

But according to Karanicolas and Zornetta, these knowledge-sharing frameworks still fall short. Researchers in the Global South often lack access to the same networks, funding, and institutional support, putting them at a disadvantage even in otherwise “open” collaborations.

Areas, such as the Global South, could be untapped sources of the desperately needed quantum talent, the article suggests.

Security, Sovereignty and Economic Stakes

The implications go well beyond academia and the authors point out just a few of the vast number of use cases quantum technology could ignite. As quantum technology matures, it could upend entire sectors. Quantum computing could crack encryption systems that currently protect financial institutions, defense networks and communication tools. Quantum sensing could revolutionize imaging and environmental monitoring. Quantum communications might form the basis of ultra-secure infrastructure.

Advanced economies, including those in the EU and North America, are already investing in these capabilities. Canada and the EU are exploring national quantum communications networks, and industry players are preparing to roll out quantum-secure cybersecurity tools.

For countries in the Global South, the risks are twofold: they may lack both the defensive capabilities to secure their infrastructure and the economic leverage to develop competitive industries in quantum-enhanced fields.

“Without meaningful access to quantum resources, the Global South may face a triple disadvantage,” Karanicolas and Zornetta write, outlining the disadvantages. “First, their security infrastructure might become increasingly vulnerable as quantum computing threatens to break existing encryption protocols. Second, their economic competitiveness might diminish as they miss opportunities to develop quantum-enhanced technologies. Lastly, their technological sovereignty might erode as dependence on external providers for quantum-resistant security becomes unavoidable.“Without meaningful access to quantum resources, the Global South may face a triple disadvantage.”

The net effect could be a deeper and more durable form of digital dependence—one that amplifies existing inequalities and limits the Global South’s ability to chart its own development path.

A Call for a New Framework

The authors point to historical precedent for managing sensitive technologies. In 1953, President Eisenhower’s “Atoms for Peace” initiative attempted to share nuclear energy technology while limiting its use in weapons development. That vision eventually shaped the global nuclear nonproliferation regime.

Karanicolas and Zornetta ask whether a similar framework — they dub it “Qubits for Peace” — might be viable for quantum technology. The goal would be to enable peaceful applications of quantum computing, sensing, and communication in less developed countries, while safeguarding military and intelligence uses.

They don’t expect it to be easy. In today’s fragmented geopolitical environment, it is unlikely that the U.S. or its allies could command the authority needed to lead such an initiative. Nor is it clear that countries in the Global South would accept new restrictions, particularly when they already face disadvantages. The difficulty of separating civilian and military quantum applications — especially in encryption — complicates matters further.

In practice, the authors suggest, the world is more likely to drift toward a fragmented quantum landscape where a few countries hold the keys to secure infrastructure, and others are forced to play catch-up with limited tools.

The Quantum Moment

The central warning of the study is that the world is repeating a dangerous pattern. As with the internet and biotechnology before it, the benefits of a transformative technology are being hoarded by the countries that develop it first.

But quantum differs in one key respect. Its security implications are immediate. If quantum computers are capable of breaking today’s encryption protocols in the near future — a risk many governments are preparing for — then the digital infrastructure of countries without quantum resilience could be exposed within a decade.

In that scenario, the quantum divide wouldn’t just slow development in the Global South, it would actively place these nations at risk.

The authors call for more inclusive collaboration, expanded research frameworks, and a reevaluation of export policies. Whether governments are willing to act on these proposals remains to be seen. But the stakes are clear.

“The changed approach towards research collaboration by major quantum powers could signal a potential pathway forward, with strategic knowledge-sharing frameworks broadened to include Global South interests and bridge the quantum divide,” Karanicolas and Zornetta write. “As governments pour resources into advancing these technologies, they need to consider strategies for ensuring that their benefits do not remain siloed across a handful of wealthy countries, and are accessible to all.”

Karanicolas is the associate professor of law and the James S. Palmer Chair in Public Policy & Law at Dalhousie University. Zornetta is a doctoral candidate at UCLA Law, specializing in the regulation of content moderation practices by online platforms.

Just Security is an editorially independent, non-partisan, daily digital law and policy journal that elevates the discourse on national security, democracy and the rule of law, and rights. This is part of the organizations Governing The Quantum Revolution series.