Insider Brief

- MIT’s William Oliver argues that quantum computing will not transform corporate IT in the short term, but decisions on security, talent and strategy made today will determine which companies benefit when the technology matures.

- Quantum computers will likely complement rather than replace classical systems, with progress now limited more by the lack of practical algorithms than by hardware, making partnerships and workforce development critical.

- Executives are advised to begin planning for post-quantum cryptography and to monitor advances in quantum error correction, which MIT identifies as the key technical barrier to achieving commercially scalable quantum systems.

- Photo by Tomasz Frankowski on Unsplash

Quantum computing is unlikely to reshape corporate IT this year, or even next year, but decisions made now could determine which companies benefit when it does mature.

Startup activity, private funding and government investment in quantum technologies are accelerating, even as fully commercial systems remain at least a decade away, and William Oliver, director of the MIT Center for Quantum Engineering told business leaders that waiting for finished machines could leave companies behind on security, workforce readiness and long-term strategic positioning.

“Advancing from discovery to useful machines takes time and engineering, and it’s not going to happen overnight,” said Oliver, according to a recent briefing connected to MIT’s Industrial Liaison Program. “But you’ve got to be in the game to play, and getting in the game is happening right now with quantum.”

Oliver laid out four practical realities for executives in his message to the business leaders. The realities were centered on understanding where quantum truly fits, where it does not and what actions companies can take now that will matter later.

Quantum computing refers to a group of technologies for sensing, networking and processing that rely on the rules of quantum physics instead of standard electrical signals, according to the briefing. Unlike classical bits, which hold either a zero or a one, quantum bits — or qubits — can theoretically represent multiple states at once and share correlated behaviors across distance. Those properties make quantum systems well suited for a narrow class of mathematically complex problems that overwhelm even the most powerful conventional computers.

Oliver emphasized that quantum will be a specialized tool, not a universal replacement. For executives, the most important question may be not whether quantum will replace today’s data centers, but where it may eventually complement them.

Quantum Will Not Replace Your Existing Computing Stack

According to Oliver, one point is usually the most misunderstood: quantum computers are not destined to replace classical computers.

Enterprise systems that run finance, human resources, customer data, cloud analytics and AI workloads will continue to depend on conventional hardware. Even as quantum machines mature, they will be used only for select classes of problems where classical methods hit hard limits.

“Quantum computers solve certain problems really well, but they’re not going to replace Microsoft Word,” Oliver said, as reported by the university.

Those use cases cluster around three domains: cryptanalysis, scientific simulation and optimization. In cryptanalysis, quantum systems could one day factor the large numbers that underpin widely used encryption schemes. In scientific simulation, they could model molecules and materials at the atomic level, something classical machines can only approximate. In optimization, they could search through massive numbers of possible solutions for problems such as supply-chain design, traffic routing or portfolio management.

For business leaders, this matters because it reframes investment strategy. Quantum is not a wholesale infrastructure replacement. It is a future accelerator for a small number of high-impact workloads. Companies that benefit most will be those that already understand where those workloads exist inside their operations.

Software, Not Hardware, Is Now the Bottleneck

The second reality is that quantum’s commercial progress is now constrained as much by software as by physics.

A small number of foundational quantum algorithms already exist, including those with direct relevance to encryption and scientific simulation. Many trace their academic roots to MIT and other major research centers. But the current library of quantum algorithms remains thin relative to the diversity of real business problems.

“There are lots of problems I’m aware of today where I don’t know how to do it on a classical computer and I also don’t yet know how to do it on a quantum computer,” he said. “We need more people thinking about the application space and writing those algorithms.”

Commercial quantum advantage — typically defined as a clear and repeatable performance edge over classical systems on a useful task — has not yet been demonstrated in production environments. That does not mean the hardware is useless. It means that the software ecosystem is still catching up to the machines being built.

For executives, this creates somewhat of a strategic gap. The limiting factor in the next phase of quantum progress may not be chip fabrication or qubit count, but the development of practical algorithms that translate quantum behavior into financial value.

This places a premium on partnerships with universities, startups and national labs that are developing quantum software. It also highlights workforce strategy. Firms that expect to use quantum in the future will need people who understand both their business problems and how those problems map onto emerging quantum methods.

Cybersecurity Must Move Before Quantum Hardware Arrives

As far as what business leaders can do today, Oliver told the group post-quantum cybersecurity is a present-day issue, not a future one.

Quantum machines powerful enough to break today’s public-key encryption systems would require millions of highly reliable, error-corrected qubits. That level of hardware does not yet exist. However, encrypted data stolen today can be stored and decrypted later once quantum machines mature.

That creates a long-term exposure window for sensitive corporate data, including intellectual property, medical records, industrial control systems and financial information. The risk is especially acute for data that must remain confidential for decades.

Oliver stressed that this is why governments are already acting. The National Institute of Standards and Technology has finalized new quantum-resistant cryptographic standards designed to withstand future quantum attacks. Federal agencies in the U.S. are already beginning mandated transitions to those standards.

For private companies, the takeaway is that post-quantum cryptography is becoming part of mainstream security planning. Firms that manage critical infrastructure or long-lived sensitive data should already be assessing where traditional encryption is used across their systems and how difficult migration will be.

This is not a capital-intensive quantum investment, according to the researcher. It is a software-driven security modernization effort that can be phased in long before quantum hardware becomes operational.

Error Correction Is the True Gatekeeper to Commercial Scale

The fourth reality looked at why quantum’s commercial timeline remains measured in decades rather than years.

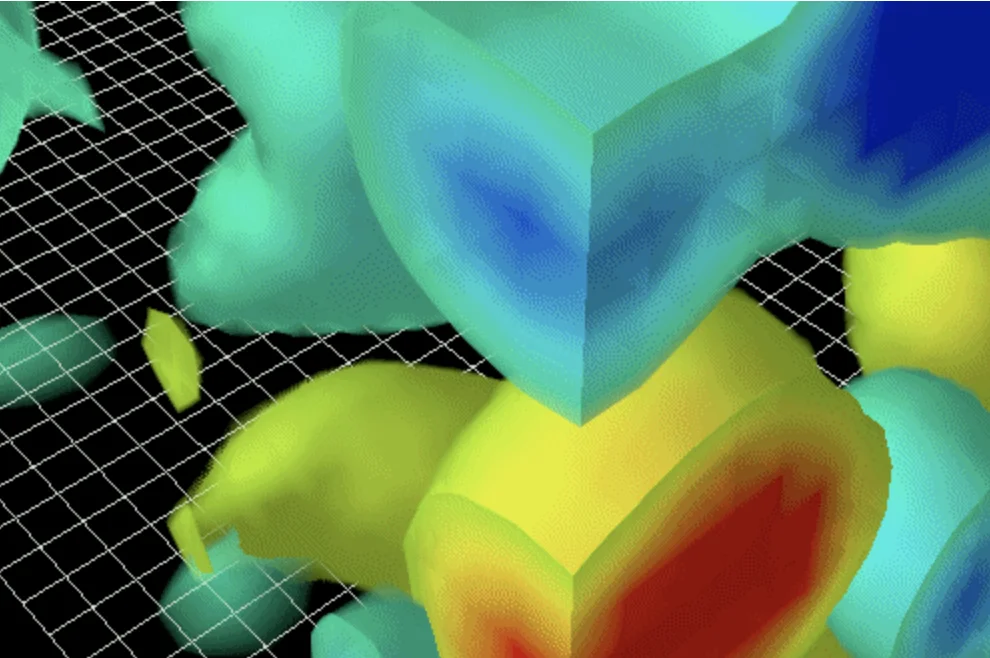

Today’s qubits are fragile. They lose information quickly due to environmental noise, heat and electromagnetic interference. Most can perform only thousands of operations before errors overwhelm useful output. By contrast, commercially valuable problems often require billions or trillions of operations.

Quantum error correction is the method used to overcome this gap. It works by encoding one reliable logical qubit across many unstable physical qubits, allowing errors to be detected and corrected in real time. The trade-off is massive overhead: a single logical qubit may require dozens, hundreds or even thousands of physical qubits.

Oliver pointed to a late-2024 milestone from Google Quantum AI as a meaningful signal. The company demonstrated that protected quantum information could become more stable as more qubits were added — a key requirement for fault-tolerant systems.

The result does not mean large-scale commercial machines are imminent. It does suggest that the basic physics required for scalability is beginning to show itself.

“We need quantum error correction to make this all possible,” Oliver said. “With the demonstration from Google last fall, we saw a major step in that direction.”

Error correction will likely dominate quantum engineering for the next decade. This also suggests that useful machines will not arrive suddenly. They will emerge gradually as reliability improves and overhead shrinks.

The MIT Industrial Liaison Program is a membership-based program for large organizations interested in long-term, strategic relationships with MIT. The group engages with organizations from around the globe, in any sector, that are concerned with emerging research- and education-driven results that will be transformative. Executive leadership who would like to learn more about the MIT Industrial Liaison Program and its MIT Startup Exchange are invited to send an email with their name, title, organization name, and headquarters location.