Insider Brief

- Quantum tunnelling is a phenomenon in which a particle passes through an energy barrier it classically lacks the energy to overcome.

- The effect arises from the wave-like nature of matter described by quantum mechanics, allowing a particle’s probability wave to extend into and beyond forbidden regions.

- First observed in radioactive decay and later in superconducting systems, quantum tunnelling underpins technologies from semiconductors to quantum computers.

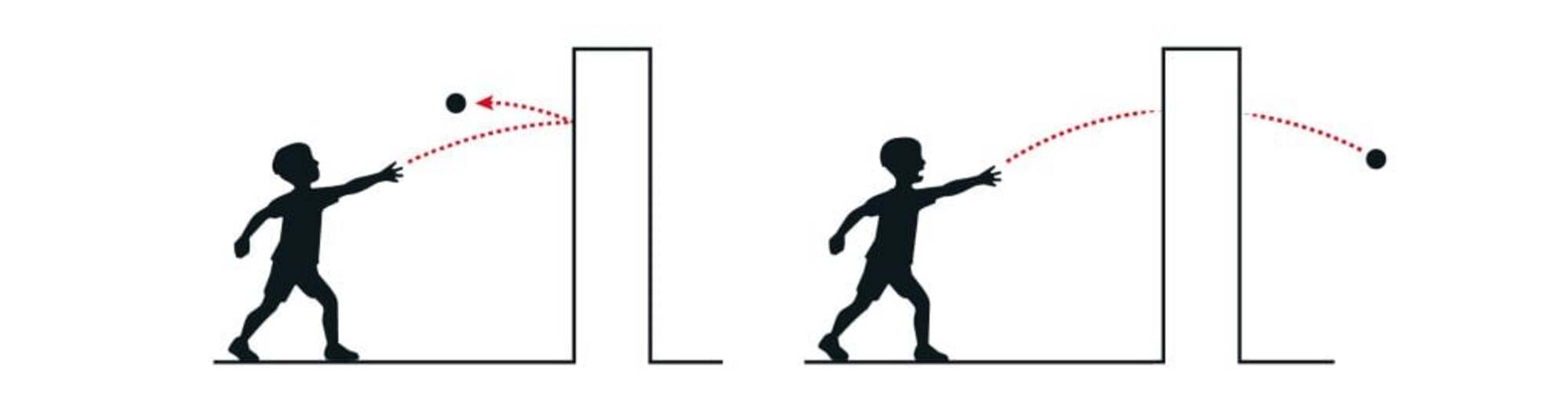

Whether it’s playing a lonely game of tennis against a garage door or shooting a game of pool at the local bar, we’re used to balls bouncing off solid objects — not passing through them. (Depending on how hard you serve, I suppose.)

It’s hard to play snooker or solo tennis in the quantum world, though.

In quantum mechanics, a particle can slip through a barrier. Although that may sound like a cross between magic and science fiction, quantum tunnelling is a real and measurable effect at the heart of modern physics. This year’s Nobel Prize in Physics recognized the scientists who proved that, while we can still bounce a tennis ball off a wall, tunnelling isn’t limited to atoms or subatomic particles.

According to the Royal Swedish Academy of Sciences, John Clarke, Michel Devoret, and John Martinis demonstrated that entire electrical circuits — large enough to hold in one’s hand — can behave like single quantum particles.

What Is Quantum Tunnelling?

Quantum tunnelling emerges from the wave-like nature of matter described by Erwin Schrödinger in 1926, according to information provided by the Royal Swedish Academy of Sciences. In classical physics, a particle can’t cross a barrier higher than its energy. Quantum physics, however, treats particles as waves that extend into classically forbidden regions. Even if a barrier is too high for a particle to cross conventionally, there is a finite probability that its wavefunction will “leak” through to the other side.

This process is called tunnelling, and, before you write it off as a scientific anomaly, it underlies several natural phenomena.

Real-World Examples of Quantum Tunnelling

| Phenomenon | How Tunnelling Works | Impact |

|---|---|---|

| Radioactive Decay | Alpha particles tunnel through the potential barrier of atomic nuclei to escape | Explains nuclear decay rates and half lives |

| Solar Fusion | Protons tunnel through electromagnetic repulsion barriers to fuse in the Sun core | Powers all solar energy and enables life on Earth |

| Flash Memory | Electrons tunnel through insulating barriers to store data in computer chips | Enables USB drives, SSDs, and smartphone storage |

| Quantum Sensors | Tunnelling currents detect minute changes in magnetic or electric fields | Used in medical imaging and materials science |

For instance, tunnelling explains radioactive decay, where alpha particles trapped inside an atomic nucleus escape through potential barriers. It also makes nuclear fusion possible in the Sun, where protons would otherwise lack the energy to overcome their mutual repulsion. The phenomenon has been verified countless times at microscopic scales and has powered technologies from flash memory to quantum sensors. Yet until the 1980s, physicists assumed tunnelling couldn’t be seen in anything larger than an atom.

From Microscopic to Macroscopic: How Did Scientists Prove Large Objects Can Tunnel?

The laureates changed that. Working at the University of California, Berkeley, Clarke, Devoret and Martinis built an electrical circuit made of superconductors — materials that carry current with zero resistance — separated by an insulating layer called a Josephson junction. When cooled to near absolute zero, this system allowed billions of paired electrons, called Cooper pairs, to move collectively as if they were a single quantum object.

By carefully measuring the circuit’s behavior, the researchers found that its electrical state could “tunnel” through an energy barrier. Instead of transitioning smoothly from one state to another, it switched abruptly, a sign that the circuit obeyed quantum, not classical, rules. They also observed that the system’s energy levels were quantized, changing only in discrete steps rather than continuously. This confirmed that a macroscopic object could indeed act as a quantum particle.

The Royal Swedish Academy described the discovery as the first clear demonstration of “macroscopic quantum tunnelling” — quantum mechanics operating in a system visible to the naked eye.

The Physics Behind the Phenomenon: What Happens During Tunnelling?

The experiment focuses on the so-called tilted washboard potential, a metaphor for the forces acting on the superconducting circuit.

The system’s electrical phase behaves like a particle trapped in a series of wells separated by energy barriers. In the classical picture, the particle would stay trapped unless pushed hard enough to escape. Quantum mechanics allows it to tunnel through the barrier instead. This event shows up as a sudden appearance of voltage across the junction, marking the moment the “particle” escapes.

By cooling the system and filtering out noise, the Berkeley team observed tunnelling at temperatures where thermal energy couldn’t explain the behavior. Their measurements agreed precisely with quantum theory’s predictions, confirming that the effect was genuinely quantum in nature.

Why It Matters: How Quantum Tunnelling Powers Modern Technology

Quantum tunnelling isn’t just a curiosity to attract a Swedish scientific committee with a large amount of prize money to give out annually. (Although, over the past half-century, quantum tunnelling has been a recurring theme in Nobel Prizes in Physics — from the 1972 award to John Bardeen, Leon Cooper, and Robert Schrieffer for the BCS theory explaining superconductivity, to the 1973 prizes recognizing Leo Esaki and Ivar Giaever for electron tunnelling in semiconductors and superconductors, and Brian Josephson for predicting tunnelling currents between superconductors.) It’s also the mechanism behind superconducting qubits — and those are the building blocks of quantum computers used by companies such as Google and IBM. The same Josephson junctions that revealed macroscopic tunnelling now serve as controllable quantum systems capable of encoding information in quantized energy states.

The Academy noted that the laureates’ experiments bridged the boundary between the microscopic and macroscopic worlds, laying the foundation for technologies that rely on manipulating quantum states at human scales. These include quantum sensors capable of detecting minute magnetic fields and new approaches to secure communication.

In essence, Clarke, Devoret, and Martinis turned quantum tunnelling from a theoretical oddity into an engineered reality, proving that the invisible laws of the quantum world can be brought into the laboratory, one superconducting circuit at a time.

Frequently Asked Questions

Can quantum tunnelling happen to everyday objects like tennis balls?

No. While quantum tunnelling has been demonstrated in macroscopic electrical circuits, the probability of tunnelling decreases exponentially with the object’s mass. A tennis ball contains roughly 10²⁵ atoms, making the tunnelling probability so infinitesimally small that it would never occur even over the lifetime of the universe. Quantum tunnelling remains a phenomenon observable only in carefully controlled microscopic and mesoscopic systems.

How does quantum tunnelling enable quantum computers?

Quantum tunnelling is the core mechanism behind superconducting qubits, the building blocks of quantum computers. Josephson junctions—the same devices used in the Nobel-winning experiments—allow quantum information to be encoded in energy states that can tunnel between configurations. This enables quantum computers to explore multiple computational paths simultaneously, giving them advantages over classical computers for specific problems.

Is quantum tunnelling faster than the speed of light?

No. While tunnelling appears instantaneous at quantum scales, it doesn’t involve information or matter traveling faster than light. The particle’s wavefunction already extends through the barrier before tunnelling occurs, and the process respects relativity’s speed limit. Quantum tunnelling is better understood as a probability phenomenon rather than conventional movement through space.

What temperature is needed to observe macroscopic quantum tunnelling?

The 2025 Nobel laureates observed macroscopic quantum tunnelling at temperatures near absolute zero (approximately -273°C or a few millikelvin). At these ultra-low temperatures, thermal noise is suppressed enough that quantum effects dominate over classical behavior. Superconducting circuits must be cooled to these extreme temperatures to maintain their quantum properties and enable tunnelling observations.

Beyond quantum computers, where else is quantum tunnelling used?

Quantum tunnelling is already embedded in everyday technology:

- Flash memory and SSDs: Store data by tunnelling electrons through insulating barriers

- Scanning tunneling microscopes (STM): Image individual atoms by measuring tunnelling currents

- Tunnel diodes: Enable high-speed electronic switches in telecommunications

- Quantum sensors: Detect minute magnetic and electric field changes for medical imaging and materials analysis

- Nuclear fusion research: Understanding proton tunnelling helps improve fusion reactor designs