Insider Brief

- A study finds that 96% of global quantum company funding now concentrates in 45 geographically dense “quantum clusters,” highlighting the increasing consolidation of commercial quantum activity.

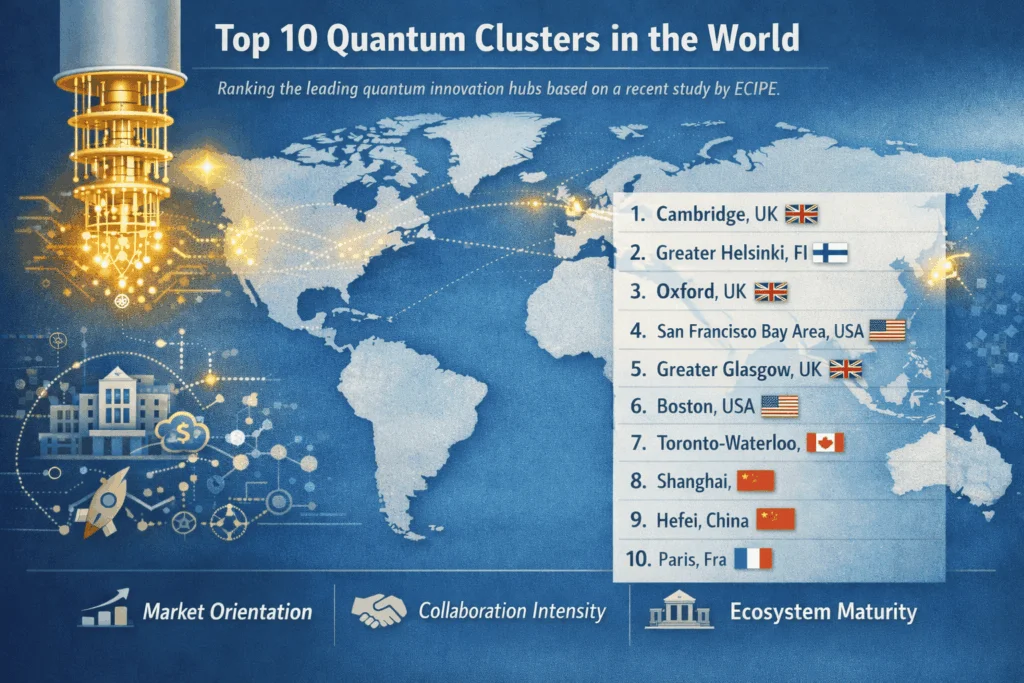

- The top-ranked clusters — led by Cambridge, followed by Greater Helsinki, Oxford, the San Francisco Bay Area and Greater Glasgow — are evaluated across three dimensions: market orientation, collaboration intensity and ecosystem maturity.

- The analysis shows the Anglosphere dominates commercialization, China leads in research-driven collaboration volume, and emerging ecosystems must concentrate capital, specialization and industry integration to compete.

- Image: Photo by Chris Boland on Unsplash

Quantum computing is not spreading evenly across the globe. It is concentrating in what is becoming a select list of the world’s leading quantum ecosystems.

A recent study by the European Centre for International Political Economy (ECIPE) finds that 96% of all global quantum company funding now flows into geographically dense ecosystems known as “quantum clusters,” up from 92% just two years ago. Only 45 regions worldwide meet the maturity threshold to qualify as full clusters.

That consolidation carries implications for investors, policymakers and industry leaders alike. Quantum’s future will not be decided country by country, but cluster by cluster.

The report, Quantum Clusters: Ranking the World’s Deep-Tech Epicentres, offers a structured global ranking of these ecosystems. The analysis aims to move beyond national comparisons and examines where research institutions, startups, capital and industry partnerships physically converge.

According to the analysts, one of the key findings is that the geography of quantum innovation is narrow, networked and dominated by a handful of regions, particularly in the English-speaking world.

What Counts as a Quantum Cluster?

The study does not treat every city with a physics department as a contender. According to the analysts, a region qualifies as a quantum cluster only if it meets two criteria. First, it must host either two startups with at least $10 million in combined disclosed funding or one startup with $25 million or more. Second, it must contain at least five institutions — research, industry, or government — actively engaged in quantum activity.

Regions that meet spatial density requirements but fall short on funding or institutional mass are labeled “quasi-clusters,” meaning they show potential but lack critical mass.

Using this framework, researchers identified 45 full clusters and 86 quasi-clusters worldwide. The overwhelming majority of commercial activity is concentrated inside those 45.

The Three Dimensions of Leadership

In the report, the clusters are ranked across three dimensions, based on the report’s methodology. The first, Market Orientation, measures funding scale, funding intensity relative to GDP and industry participation. The second, Collaboration Intensity, evaluates volume of institutional partnerships, external openness and brokerage roles. The third, Ecosystem Maturity, assesses institutional density and long-term innovation capacity.

The overall ranking averages performance across all three with Cambridge, U.K., leading globally, followed by Greater Helsinki, Oxford, the San Francisco Bay Area and Greater Glasgow.

As mentioned, English-speaking countries account for the majority — specifically 10 of the top 15 clusters. The analysts suggest that dominance reflects strong venture ecosystems, tight research–industry integration and established commercialization pathways.

The strongest differentiator among clusters is commercialization. In absolute funding terms, the San Francisco Bay Area stands alone. Quantum companies in Silicon Valley have attracted roughly $6.2 billion, representing about 29% of global quantum company funding, according to the report.

Greater Washington and Denver–Boulder follow, each exceeding $2 billion. Together, three U.S. clusters account for more than half of global quantum funding.

Outside the U.S., only a handful approach that scale. China’s Shenzhen–Hong Kong–Guangzhou region and Hefei each surpass $1 billion. Paris exceeds $750 million, making it the European Union’s most heavily funded cluster. London trails at roughly $423 million.

The analysts report that the asymmetry between the quantum haves and quantum have-nots is stark. While Europe and China boast deep research activity, large-scale private capital remains concentrated in American ecosystems.

Yet, in the case of quantum clusters, the analysts report that absolute funding tells only part of the story.

When venture, equity and debt funding are measured relative to GDP, smaller innovation-driven regions rise to the top. Cambridge leads globally in funding intensity, with quantum startup funding exceeding 1.3% of local GDP. Greater Helsinki and Denver–Boulder also rank near the top on this relative metric.

Based on the data, two distinct models emerge. One model is the frontier-tech giant, where quantum rides atop broader startup dynamism — Silicon Valley and Tel Aviv fit this pattern. The second is the specialized quantum hub, where quantum constitutes a disproportionately large share of innovation activity, as in Cambridge, Helsinki and Denver–Boulder.

The latter suggests that smaller economies can “punch above their weight” if they focus strategically.

Commercialization Beyond Funding

While it seems to gather most of the headlines and earn most of the attention, the analysts report that capital alone does not guarantee maturity.

The study uses industry-involving collaborations relative to GDP as a proxy for commercialization depth. Here, Cambridge again leads, followed by Oxford and Canberra. These ecosystems demonstrate unusually tight linkages between universities and spinout firms. The analysts point to the importance of companies that bridge academic research and industrial needs, reinforcing a virtuous cycle of translation.

Interestingly, Silicon Valley ranks lower on this relative metric despite dominating funding. The Bay Area’s ecosystem is large and capital-rich, but its industry collaboration intensity relative to economic size is more moderate.

That suggests some smaller ecosystems may be more tightly integrated across academia and industry than larger venture-driven markets.

For policymakers, that distinction matters. Funding and institutional integration are not interchangeable.

China’s Research Strength — Collaboration Intensity

If commercialization is an Anglosphere strength, collaboration density tells a different story.

Shanghai ranks first globally in collaboration intensity, followed by Greater Los Angeles and Karlsruhe. Chinese clusters, including Beijing, Shenzhen–Hong Kong–Guangzhou and Hefei, dominate rankings for total institutional collaborations.

However, the report indicates that the overwhelming majority of these collaborations involve research institutions. That reveals an important nuance: Chinese clusters exhibit enormous academic density, but comparatively less industry-led commercialization than top U.S. or U.K. hubs.

Size also influences openness with larger clusters tending to rely more on internal collaboration, while smaller ecosystems depending more heavily on external partnerships to access specialized capabilities.

Only a handful of clusters play a genuine brokerage role — connecting otherwise disconnected regions. Greater Glasgow, Karlsruhe, Geneva, Bangalore, Montreal and Shanghai stand out as bridging hubs.

In a field where hardware platforms, communications systems and quantum error correction approaches remain fragmented globally, such connector clusters help integrate capabilities across borders.

Europe: Dense, but Fragmented

The study paints a mixed picture of the European quantum landscape.

The U.K. — already mentioned several times as a leading quantum cluster — stands out with five clusters in the global top tier: Cambridge, Oxford, Greater Glasgow, Bristol–Bath and London.

Within the EU, Greater Helsinki and Karlsruhe are the strongest performers. Paris attracts the largest funding pool among EU clusters, but its overall ranking remains mid-tier.

Southern European hubs such as Barcelona and Valencia rank lower and attract modest private investment.

Europe’s challenge, based on the report’s analysis, is not research output. It is capital mobilization and industrial translation.

North America’s Commercial Concentration

North America is dominated by the United States with the San Francisco Bay Area alone attracting nearly twice the total quantum funding of all European clusters combined and boosted by leadership in the Denver–Boulder, Greater Washington and Greater Boston ecosystems.

Canada plays an important role through the Toronto–Waterloo corridor, which ranks among the global top 15. Montreal ranks lower, reflecting smaller scale and funding constraints.

The U.S. advantage lies not merely in research but in its venture ecosystem and ability to scale infrastructure-heavy projects.

East Asia: Research Depth, Uneven Commercialization

China accounts for six of East Asia’s ten clusters. Hefei is the region’s strongest performer and the only Chinese cluster in the global top 15. It has attracted more than $1.1 billion in funding.

The Shenzhen–Hong Kong–Guangzhou region has raised over $1.3 billion, though its lower ranking suggests that funding alone does not guarantee ecosystem sophistication.

Shanghai and Beijing occupy middle-tier positions, reflecting strong academic ecosystems but less mature market orientation.

Outside China, Tokyo and Singapore show moderate performance. Seoul ranks lower and remains an emerging ecosystem.

Why Clusters Matter More Than Countries

The analysts argue that quantum innovation depends on dense co-location of talent, capital and institutions. Ultra-specialized infrastructure cannot be easily replicated. Talent pools are scarce. Supply chains remain immature. Importantly, the study suggests that no single region holds all capabilities required for scalable quantum systems.

Clusters combine three reinforcing advantages: economies of scale, knowledge spillovers and structured collaboration across disciplines. The result is a hybrid innovation model with clusters that may be geographically concentrated, but networked globally.

For governments, the implication is that national strategy without cluster strategy may miss the point.

One of the critical findings is that — rather than diffusing — quantum commercialization is consolidating.

Cluster concentration rose from 92% of global funding through 2023 to 96% in 2025, according to the report.

That suggests the next decade may see intensification around existing leaders rather than broad geographic expansion. Emerging quasi-clusters may grow. But breaking into the top tier requires both capital depth and institutional density — thresholds that are rising, not falling.

How Emerging Quantum Ecosystems Can Compete

Because the rankings in the report name leaders, it’s disingenuous to consider this a zero sum game. Though not explicitly covered in the paper, policy makers, businesses and organizations could lift some tips from the study to bolster their roadmaps for building and strengthening their clusters.

For example, research density does not automatically translate into startup formation, venture capital attraction, or industrial integration. Accelerating spinouts, embedding venture capital early, and structuring industry participation alongside academic research appear to be key differentiators among top-performing clusters such as Cambridge, Oxford, and Helsinki.

The report also covers two distinct models of success. Some ecosystems — specifically Silicon Valley and Tel Aviv — leverage broad frontier-technology dynamism to support quantum growth. Others, including Helsinki and Denver–Boulder, achieve outsized impact by concentrating deeply on quantum as a niche specialization.

For smaller economies, if replicating Silicon Valley’s scale is daunting, if impossible, ecosystem builders may choose to specialize. But building global leadership in a specific segment of the quantum stack — such as photonics, quantum sensing, cryptography, or error correction — is achievable. Funding intensity relative to GDP, rather than absolute dollars raised, often distinguishes these focused hubs.

Improving network position is yet another way to strengthen quantum ecosystems. Smaller clusters tend to rely more heavily on external collaborations, according to the study. Rather than a weakness, that outward orientation can become a structural advantage. A handful of mid-sized ecosystems — including Karlsruhe, Geneva, and Glasgow — rank highly as “brokerage” hubs, connecting otherwise disconnected regions in the global quantum network.

Ultimately, the study suggests that in a field where hardware platforms, communication technologies and quantum error-correction approaches remain fragmented, serving as a connector can increase visibility and attract partnerships disproportionate to local economic scale.

Finally, industry integration emerges as a critical signal. Clusters that rank highest in commercialization intensity tend to embed industry actors early and consistently in research partnerships. The report suggests that tight university–industry linkages are not downstream outcomes of maturity; they are drivers of it.

Ultimately, emerging ecosystems are unlikely to compete by dispersing small grants across multiple regions or by emphasizing research output alone. They are more likely to gain traction by concentrating capital, accelerating spinouts, embedding industry from the outset and positioning themselves within global collaboration networks.