Insider Brief

- Researchers at Iceberg Quantum report in an arXiv preprint that their “Pinnacle Architecture” could factor RSA-2048 using fewer than 100,000 physical qubits under standard hardware assumptions, significantly below many prior estimates.

- The design replaces surface codes with quantum low-density parity-check (QLDPC) codes and uses modular processing units, “magic engines,” and memory blocks to reduce error-correction overhead while maintaining universal quantum computation.

- The team points out that the results are based on simulations and theoretical resource estimates rather than experimental demonstrations.

A new fault-tolerant quantum computing architecture could factor a 2048-bit RSA integer using fewer than 100,000 physical qubits — an order of magnitude less than many estimates — according to a study posted on the pre-print server arXiv by researchers at Iceberg Quantum and announced in a recent company release.

Dubbed the “Pinnacle Architecture,” the system relies on quantum low-density parity-check (QLDPC) codes rather than the more commonly analyzed surface codes, which have dominated most large-scale resource estimates to date. Under standard hardware assumptions — assuming hardware that makes errors roughly once in every thousand operations and can detect and correct them in millionths of a second — the researchers report that RSA-2048 factoring could be achieved with under 100,000 physical qubits.

If confirmed, the findings would significantly narrow the gap between current quantum hardware roadmaps and the scale required for cryptographically relevant applications. Previous leading estimates placed the requirement near or above one million physical qubits for similar error assumptions.

Quantum computers are inherently error-prone. Each qubit — which is the quantum equivalent of a classical bit — is vulnerable to noise from its environment. To run long computations, researchers encode “logical qubits” into many physical qubits using error-correcting codes. The dominant approach, the surface code, typically requires hundreds to thousands of physical qubits per logical qubit to suppress errors to usable levels.

That overhead has driven the assumption that breaking RSA-2048 would require on the order of a million physical qubits. Scaling hardware to that level remains a formidable engineering challenge.

Magic Engine and Memory Blocks

The Pinnacle Architecture replaces surface codes with QLDPC codes, a class of error-correcting codes in which each qubit interacts with only a small number of others, even as the machine grows. That structure allows errors to be detected without complex, all-to-all connections, an advance that keeps correction circuits faster and reducing the number of physical qubits needed per logical qubit.

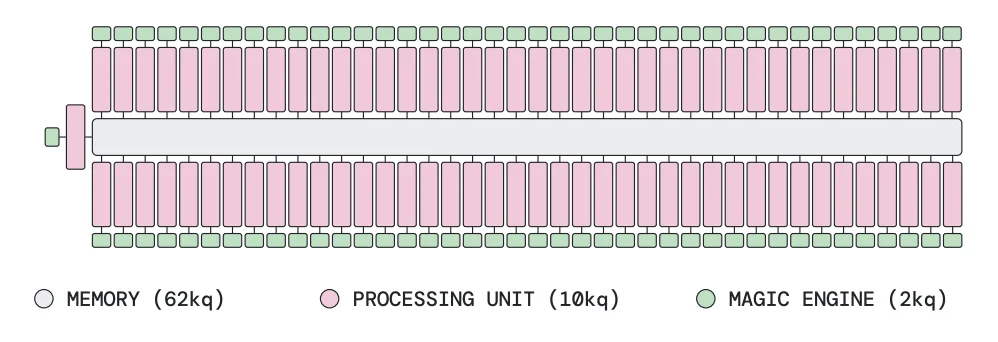

To dive a little deeper, the architecture is built from modular “processing units,” “magic engines,” and optional “memory” blocks. Each processing unit consists of QLDPC code blocks — the error-correcting structures that protect the logical qubits — along with measurement hardware that enables arbitrary logical Pauli measurements during each correction cycle. In practical terms, that allows the system to perform whatever protected operation the algorithm requires at each step. When combined with injected “magic states” — special resource states used to enable more complex operations — those measurements are sufficient for universal quantum computation, meaning the machine can run any quantum algorithm.

In the Pinnacle design, a “magic engine” produces one encoded magic state per logical cycle while simultaneously consuming one prepared in the previous cycle. This pipeline is designed to maintain steady throughput without sharply increasing hardware overhead.

The architecture hints at the difference between surface codes and QLDPC. Surface codes require dense, grid-like local connectivity and many qubits per logical qubit. QLDPC spreads parity checks more sparsely across a block.

One way to picture the difference is wiring. Surface codes are like protecting data by wiring every component into a dense grid — reliable, but heavy and hardware-intensive. QLDPC codes achieve protection with far fewer connections per qubit, more like a sparsely wired network that still catches errors but uses much less hardware.

Benchmarking Against RSA and Materials Science

To test the architecture, the researchers compiled two benchmark problems. They estimated the ground-state energy of the Fermi-Hubbard model, a widely studied problem in condensed matter physics. They also analyzed the resources required to factor 2048-bit RSA integers.

For the Fermi-Hubbard model on a 16×16 lattice — effectively a 256-site simulation of interacting electrons — with realistic coupling parameters, the study reports that about 62,000 physical qubits would suffice at a physical error rate of 10⁻³, compared with roughly 940,000 under a prior surface-code-based estimate. At lower physical error rates of 10⁻⁴, the requirement drops to roughly 22,000 physical qubits.

For RSA-2048 factoring, the headline result is under 100,000 physical qubits at a physical error rate of 10⁻³ and a 1-microsecond code cycle time. The analysis assumes a reaction time — the delay between measurement and adaptive response — equal to ten times the code cycle time.

The researchers also modeled slower hardware. With millisecond-scale cycles, RSA-2048 factoring would take roughly a month using about 3.1 million qubits at a physical error rate of one in ten thousand, or roughly 13 million qubits at about one in a thousand. The difference reflects a hardware–runtime trade-off: more qubits allow greater parallelization, reducing execution time.

An innovation that boosted this flexibility is what the team calls “Clifford frame cleaning,” a technique that allows processing units to be joined and later separated with limited additional logical measurements. This supports selective parallelism without fully entangling the entire machine’s logical state.

The team implemented the design using a family of QLDPC codes known as generalized bicycle codes, essentially a structured approach to error correction that limits how many qubits must interact. They simulated the system under a standard circuit-level depolarizing noise model, which assumes small random hardware errors, and used the results to estimate logical error rates and scaling behavior.

For decoding — the process of inferring which physical errors occurred — the simulations use most-likely-error decoding, implemented as an optimization problem. The study pointed out that decoder speed for real-time hardware control is outside its scope.

Logical error rates from the simulations guided the choice of code distance. For example, at a physical error rate of about one error in a thousand, the researchers used a code distance of 24 to keep logical errors low enough to run long RSA circuits reliably.

The RSA resource estimate builds on a variant of Shor’s algorithm that uses residue number system arithmetic to shrink the size of the working register. The Pinnacle Architecture extends that approach by processing subsets of primes in parallel, trading more qubits for shorter runtime.

Throughout the analysis, the researchers assume physical error rates between roughly one in a thousand and one in ten thousand — levels consistent with leading superconducting, neutral-atom and trapped-ion platforms — and error-correction cycle times between one microsecond and one millisecond.

Implications for Cryptography

RSA-2048 serves as a key line of cyber defense for much of today’s public-key cryptography. Although most experts expect post-quantum cryptographic schemes to replace RSA before large-scale quantum computers are built, hardware timelines remain uncertain.

If fewer than 100,000 physical qubits were sufficient to break RSA-2048 under realistic error models, the threshold for cryptographic risk could arrive sooner than many surface-code-based estimates imply.

To be sure, the result remains conditional on several factors, including achieving sustained physical error rates at or below about one error in a thousand, implementing efficient QLDPC decoding in real time and integrating modular hardware at scale.

The study outlines the architecture as modular and compatible with hardware platforms that support quasi-local connectivity, rather than requiring full all-to-all qubit interactions. That constraint is intended to align the design with likely physical architectures.

Future Work

The team reports on both the limitations and a path for future work to address those limitations in the study.

First, it’s important to note that the analysis is based on numerical simulations and theoretical compilation, not experimental demonstration. Logical error rates are extrapolated from fitted models, and the decoding method used in simulation may not reflect practical, low-latency decoders required for real machines.

Magic state distillation, though optimized in the architecture, remains a dominant cost. The rejection rate of distilled states increases at higher physical error rates, requiring idle cycles and slightly increasing logical depth.

While the qubit count is reduced relative to prior surface-code estimates, building and stabilizing even 100,000 high-fidelity qubits with microsecond-scale cycles remains far beyond current hardware, which typically operates in the hundreds to low thousands.

Even with those caveats, the Pinnacle Architecture reframes the scale at which “utility-scale” quantum computing might emerge. By combining QLDPC codes, modular processing units and pipeline-style magic state production, the study argues that the million-qubit threshold may not be fundamental.

For a deeper, more technical dive, please review the paper on arXiv. It’s important to note that arXiv is a pre-print server, which allows researchers to receive quick feedback on their work. However, it is not — nor is this article, itself — official peer-review publications. Peer-review is an important step in the scientific process to verify results.

The Sydney, Australia-based Iceberg Quantum research team included Paul Webster, Lucas Berent, Omprakash Chandra, Evan T. Hockings, Nouedyn Baspin, Felix Thomsen, Samuel C. Smith and Lawrence Z. Cohen.