Insider Brief

- Researchers demonstrated that two particles levitated by a steady sound wave can enter a self-sustaining, repeating motion known as a classical time crystal without external timing or quantum effects.

- The system relies on nonreciprocal sound-mediated forces between slightly different particles, allowing energy from a static acoustic field to balance friction and maintain long-lived oscillations.

- The findings show that time-translation symmetry can be broken in ordinary physical systems, opening potential paths toward compact oscillators and sensors based on classical physics.

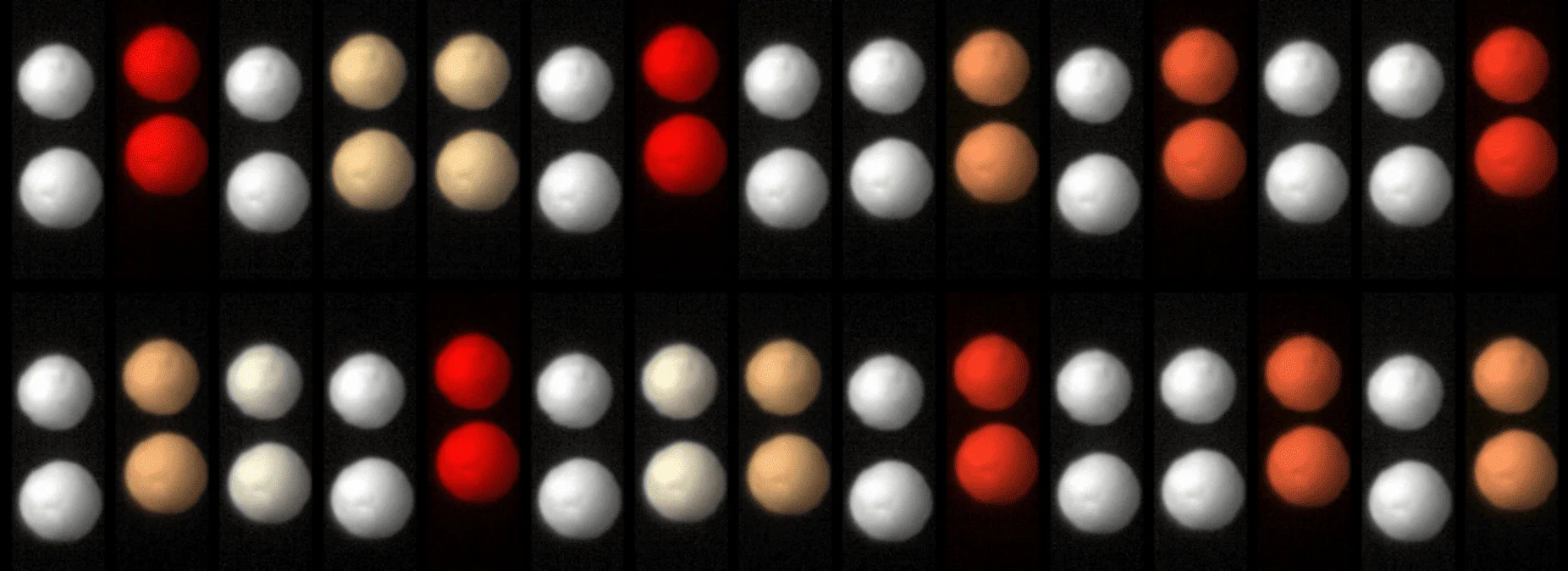

- Image: A stop-motion image that shows pairs of millimeter-scale beads forming a time crystal over approximately one-third of a second in time. The colors represent the beads interacting at different stages during this period. (NYU’s Center for Soft Matter Research)

A pair of tiny particles levitated by sound waves can lock into perpetual motion without external timing, offering a new way to build self-sustaining oscillators and challenging assumptions about how time-ordered systems must work.

That is the central finding of a new study by researchers at New York University, who report that two millimeter-scale particles suspended in an acoustic standing wave can enter a stable, repeating cycle of motion — known as a time crystal — despite friction and without periodic driving. The work shows that time crystals, once thought to be primarily a quantum phenomenon, can arise in ordinary, classical systems through carefully structured interactions.

The study, published in Physical Review Letters, demonstrates that nonreciprocal forces — interactions where action and reaction are not equal — allow the system to continuously draw energy from a static sound field and convert it into long-lived motion. Under specific conditions, the oscillations break time-translation symmetry, meaning the system changes over time even though the governing rules do not.

According to the university, the results expand the growing family of time-crystal systems while also expanding the prospects that these crystals hold for technology and industry, such as uses in sensing, signal generation and mechanical timing devices.

The researchers added that these time crystals, which can be seen with an unaided eye, are suspended on a one-foot-high device that you can hold in your hand.

“Time crystals are fascinating not only because of the possibilities, but also because they seem so exotic and complicated,” said Physics Professor David Grier, director of NYU’s Center for Soft Matter Research and the paper’s senior author, in a university release. “Our system is remarkable because it’s incredibly simple.”

Breaking Time Symmetry With Sound

A little background: Time crystals are systems that repeat in time the way ordinary crystals repeat in space. Instead of atoms arranged in a fixed pattern, a time crystal cycles through motion at a steady rhythm. The defining feature is that this motion emerges on its own rather than being imposed by an external clock.

In the NYU experiment, researchers used an acoustic levitator, a device that traps small objects at pressure nodes created by a standing sound wave. Each node acts like a shallow bowl, holding a lightweight bead in place. When two beads are trapped near each other, they interact by scattering sound waves back and forth.

Those scattered waves generate forces between the particles, according to the research team, which included Mia Morrell, an NYU graduate student, and Leela Elliott, an NYU undergraduate. The team adds that, importantly, the forces are not always equal in both directions if the particles differ slightly in size. This asymmetry allows the pair to extract energy from the surrounding sound field.

Most of the time, friction from air quickly damps any motion, leaving the particles motionless. But the researchers found that for certain size combinations, the energy gained from these asymmetric interactions exactly balances the energy lost to drag. When that happens, the particles settle into a steady rhythm of motion.

Depending on the parameters, the particles can move together in sync or oscillate in opposition, like two masses connected by an invisible spring. In one regime, the oscillation breaks both spatial and temporal symmetry, meeting the formal definition of a continuous time crystal.

The system requires no external timing signal. The sound wave that holds the particles in place is static and the oscillation frequency emerges from the dynamics of the particles themselves.

How the Researchers Built the System

As mentioned, the experiment uses a relatively simple setup. The levitator operates at 40 kilohertz, well above the range of human hearing and creates a line of pressure nodes spaced a few millimeters apart. Expanded polystyrene beads — lighter than air but stiff enough to scatter sound — are placed into adjacent nodes.

High-speed cameras track the motion of the beads over long periods, sometimes hundreds of seconds at a time. The researchers analyze the motion by separating it into collective modes and measuring the frequency content of each.

Alongside the experiments, the team developed a theoretical model that captures how sound-mediated forces act between the particles. The equations describe how restoring forces, drag and nonreciprocal interactions combine to determine whether motion grows, decays or stabilizes.

The model predicts clear boundaries between passive states, ordinary oscillators and time-crystal behavior. Measurements from the experiments align closely with those predictions, including the frequencies and stability of the observed oscillations.

One striking result is the coherence of the motion. In some cases, oscillations persist for hours, far longer than the time it would take friction alone to stop them. That persistence is a key requirement for any practical timing or sensing application.

Why This Matters for Technology

The findings suggest a new way to design compact oscillators and detectors that do not rely on electronic feedback or external clocks. Because the oscillation frequency emerges from the system itself, such devices could be inherently stable against certain types of noise.

More broadly, the work shows that dissipation — the loss of energy to the environment — does not always destroy order. Under the right conditions, dissipation can help stabilize it. That idea runs counter to traditional engineering intuition, which typically treats friction and loss as problems to be minimized.

The study also highlights the role of nonreciprocal interactions as a source of sustained activity. Similar effects appear in optics, mechanics and electronics, suggesting the underlying principles could be translated into other platforms.

The authors note that larger arrays of particles could show even richer behavior, including transitions between wave-like motion and localized activity. Such systems could serve as testbeds for studying how order emerges in driven, nonequilibrium systems.

What This Means — and Doesn’t Mean — for Quantum Technology

Time crystals are often associated with quantum systems because they were first proposed in quantum systems. However, the researchers emphasize that this work is entirely classical. The particles follow ordinary laws of motion and no quantum coherence or entanglement is involved.

The study does not advance quantum computing, at least directly, nor does it offer a new way to store or process quantum information. However, those in the quantum industry may see this work as a way to advance quantum by clarifying which aspects of time-crystal behavior depend on quantum mechanics and which do not.

For quantum engineers, that has value because quantum time crystals face major challenges from noise and heating. The acoustic system shows how symmetry-breaking motion can be stabilized using dissipation and nonreciprocal coupling — tools that also exist in quantum hardware, such as microwave circuits and photonic networks.

By providing a clean, controllable classical example, the work offers insight into how timing and oscillatory phases might be engineered in more fragile quantum systems. It also helps separate genuine quantum advantages from behaviors that classical physics can already reproduce.

Limits and Next Steps

The system relies on carefully tuned particle properties. If the particles are too similar, the interactions become reciprocal and the oscillations disappear. The effect also depends on operating within a narrow range of sizes and coupling strengths.

Scaling the system beyond a few particles introduces additional complexity, including disorder and competing modes of motion. Understanding how those factors interact will be key to any practical application.

Future work will likely explore other wave-based platforms, including optical and mechanical systems, to test whether similar principles apply. Researchers may also investigate whether such time-crystal behavior can be harnessed for sensing weak forces or environmental changes.