Guest Post by Komala S Madineedi

Quantum computing has moved beyond theory. Real quantum systems exist today, and a growing number of companies offer products and platforms built around them. In select domains, these systems are already being used to explore problems that are difficult or impractical to address with classical methods alone – particularly in combinatorial optimization, quantum simulation, financial modeling, and cryptography.

Much of today’s applied work focuses on optimization-heavy problems such as scheduling, routing, and portfolio construction, where hybrid quantum-classical approaches are being actively explored. In cryptography, the relevance is already concrete. The anticipated impact of future quantum attacks has accelerated global adoption of post-quantum cryptographic standards, even before large-scale fault-tolerant quantum computers exist.

At the same time, “existence” should not be confused with maturity. Many quantum products remain nascent in an operational sense: performance can be sensitive to calibration and environment, workloads are often narrow or carefully structured, and meaningful usage frequently requires close involvement from specialized teams. Reliability, uptime, and cost predictability – standard expectation in mature computing platforms – are still uneven.

This does not diminish recent progress. Fault-tolerant quantum computing, long treated as a distant theoretical goal, is becoming more concrete through below-threshold error-correction demonstrations and increasingly explicit system roadmaps. In parallel, the surrounding ecosystem – components, tooling, and system architectures – is beginning to professionalize beyond bespoke lab builds.

For founders and enterprise leaders, the implication is subtle but important: while quantum computing is no longer hypothetical, it cannot yet be treated as a mature product platform. The central question is no longer whether quantum systems work, but what kind of products these early systems actually are – and what it would take to turn them into scalable, durable offerings.

Early Product-Market Fit Is Real – But Narrow

While quantum computing has achieved product-market fit, it has done so only innarrow, well-defined contexts. There are application areas today where quantum systems are being deployed and where early adopters see enough value to justify engagement. For example: In 2025, HSBC reported that quantum computing trials improved aspects of bond trading workflows, demonstrating practical – if highly scoped – value in a real financial setting. These deployments matter because they validate technical direction and provide credible signals about where future value may emerge. Broader industry reporting echoes this pattern.

However, this early PMF should not be confused with broad product-market fit at scale. Even within these niches, solutions are often highly tailored, operationally intensive, and difficult to generalize across customers or environments. What works for one problem instance or system configuration rarely translates cleanly into repeatable value across many.

At this stage, PMF reflects directional validation rather than market maturity. Recognizing this distinction avoids both (i) dismissing real progress as irrelevant and (ii) overinterpreting early success as evidence that scalable markets are imminent.

The Scale Gap: From Early Success to Scalable Products

The central challenge in quantum computing today is not identifying promising applications but bridging the gap between early success and scalable products.

A useful way to frame this gap is through three gates that define readiness for scale, not the legitimacy of early experimentation:

- Technical validity – verifiable, meaningful results under realistic conditions.

- Productization – repeatable workflows that do not require bespoke scientific effort.

- Market scalability – solutions make economic sense across customers and compete with classical alternatives.

Many quantum efforts today clear the first gate. Fewer reliably clear the second. Very few have crossed the third. This does not invalidate early deployments – it places them in the correct temporal context.

What makes this moment particularly interesting is that the bottleneck is shifting. As fault tolerance becomes more tangible, constraints move up the stack: system architecture, real-time control and error decoding, classical-quantum integration, operations, and manufacturability. These factors increasingly determine whether early success can evolve into scalable products.

Scaling Is Now a Systems Engineering Problem

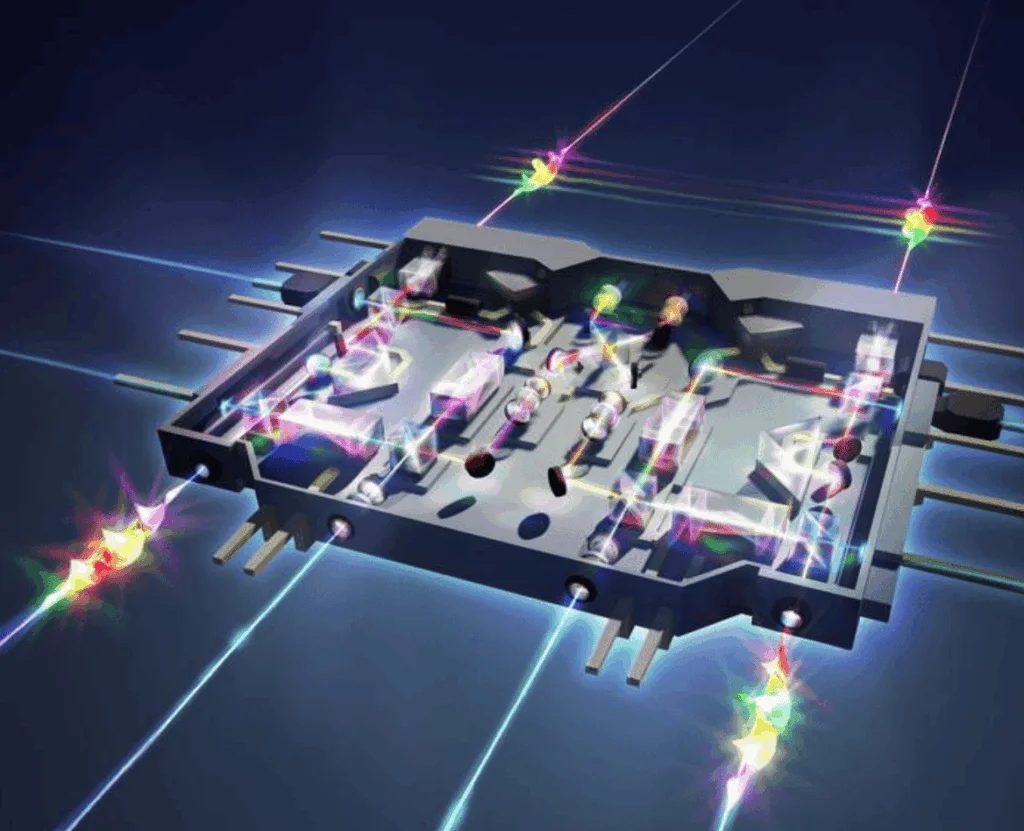

As quantum systems grow, error correction introduces substantial overhead in qubits, measurement cycles, and real-time decoding. Control and readout demand dense interconnects, precise timing, and high-bandwidth interfaces across extreme temperature gradients. Calibration, drift management, testing, and metrology grow more expensive as systems scale.

A system that requires constant expert intervention may be scientifically impressive, but it fails the bar of a deployable product. In this sense, many current quantum systems still resemble advanced laboratory instruments more than commercial computing platforms.

The shift toward modular and networked architecture reflects an acknowledgment of these realities. Rather than scaling solely through larger monolithic systems, the field is increasingly treating architecture and integration as first-class design problems. Scaling quantum is now fundamentally a systems engineering challenge, not just a physics one.

Commercialization Before Scale

Given these constraints, commercialization today is less about delivered turnkey solutions and more about laying foundations for future scale. This includes enterprise partnerships, platform access models, co-development efforts, and tooling that helps organizations learn and prepare.

Early revenue and partnerships are meaningful, but they should be interpreted carefully. They signal interest, strategic positioning, and long-term planning – not proof that scalable markets have arrived. When early commercial activity is framed as evidence of near-term maturity, expectations become misaligned and pressure builds to overpromise.

A healthier framing treats commercialization at this stage as preparatory rather than conclusive: reducing uncertainty, identifying credible application pathways, and building the ecosystem required for future products to succeed.

Next Steps: What Good Product Management Looks Like in Quantum

In this environment, product management is not a downstream execution role – it is a central coordinating function. As of today, Quantum product management looks far closer to hardware platform development than to SaaS-style iteration. Development cycles are long, system-level decisions are costly and often irreversible, and progress depends on aligning physics, engineering, operations, and economics under deep uncertainty.

A poor PM amplifies noise. They chase headline benchmarks that do not translate into real-world usage, treat roadmaps as marketing artifacts, or mistake research milestones for product readiness. This behavior creates misalignment between technical reality and market expectations, increasing the risk of overpromising and underdelivering.

A good quantum PM does something much harder.

First, they understand the technology one level deep – enough to reason about constraints, trade-offs, and failure modes without needing to be the domain expert. This enables them to ask better questions: what actually limits scalability here, which assumptions are fragile, and which improvements meaningfully move the system closer to repeatable use?

Second, they differentiate signal from noise. In a field saturated with pilots, benchmarks, and claims of advantage, effective PMs develop judgment about what generalizes and what does not. They are cautious about extrapolating from instance-specific results and disciplined in evaluating whether a use case can survive real-world variability and operational constraints.

Third, they sequence decisions honestly. Rather than forcing premature commitments to markets or timelines, strong PMs align product strategy with technical readiness. They optimize first for product development, then for robustness, and only then for scale – resisting pressure to collapse these phases into one.

Most importantly, effective quantum PMs act as translators. They translate between researchers and executives, between technical milestones and customer value, and between long-term ambition and near-term reality. They help organizations communicate progress credibly – internally and externally – without either underselling real advances or overstating maturity.

In a field where uncertainty is structural rather than incidental, this ability to translate, constrain, and sequence is foundational to turning quantum computing from scientific progress into sustainable products.

Disclaimer: The views expressed here are the author’s own and do not represent those of her employer or any affiliated organizations.

Bio: Komala S Madineedi is a hardware product leader with over a decade of experience in semiconductors and deep-tech systems. Her current interests lie at the intersection of quantum computing, emerging compute architectures, and product strategy – bringing practical product management thinking to complex, early-stage technologies. She holds an M.S. in Electrical Engineering from Penn State University and an MBA from Chicago Booth, with concentrations in economics, entrepreneurship, marketing, and strategy.