Insider Brief

- Venture capital investors are becoming more selective in quantum computing, shifting from broad enthusiasm toward architectures and companies that show credible paths to fault tolerance, manufacturing scale, and economic utility.

- External validation from government programs, particularly DARPA’s Quantum Benchmarking Initiative, is increasingly being used by investors as an independent filter to assess technical claims and long-term viability across competing quantum approaches.

- While multiple qubit modalities remain in play, investors are paying closer attention to error rates, physical-to-logical qubit overhead, and supply-chain readiness, with growing interest in silicon-based platforms and near-term applications such as quantum sensing and navigation.

- Photo by geralt on Pixabay

A new wave of quantum investment may be moving beyond headline metrics and looking more intently at external validation and manufacturing realism, while focusing on error rates rather than qubit counts, according to a recent analysis by senior partners at DCVC, a Silicon Valley venture firm known for early bets on frontier technologies.

In the blog post, DCVC Co-Founder and Managing Partner Matt Ocko, General Partner James Hardima and Operating Partner Prineha Narang, who also serves as the Howard Reiss Chair in Physical Sciences at UCLA, report that quantum computing has entered a more disciplined phase, one in which technical milestones, government scrutiny and architectural tradeoffs are beginning to matter as much as ambition.

“We’re excited to see growing evidence that quantum computing has reached an inflection point, reinforcing our multi-decade conviction as a pioneer investor in this space,” the team writes. “While significant engineering challenges remain on the path to commercial deployment, these are exactly the kinds of technical problems that drive innovation and create opportunity. Rather than getting swept up in hype cycles, we’re taking a disciplined, long-term approach to this emerging technology – understanding that meaningful breakthroughs require both vision and patience.”

According to the DCVC analysts, the industry is moving quickly but unevenly, with breakthroughs in laboratory performance colliding with the harder work of scaling, manufacturing, and reducing error. Venture capital, they suggest, is responding by narrowing its focus, prioritizing platforms that can plausibly transition from research demonstrations to utility-scale machines.

Excitement to Validation

The post places today’s quantum momentum against a backdrop of growing government involvement and independent assessment. The U.S. Department of Energy’s recent $625 million funding allocation for the National Quantum Information Science Research Centers, created under the National Quantum Initiative Act, is cited as evidence that quantum technology has moved firmly into the realm of national strategic interest.

More consequential for investors is the role of the Defense Advanced Research Projects Agency, the analysts argue. DARPA’s Quantum Benchmarking Initiative is described as a rare attempt to impose a rigorous, skeptical framework on a field long dominated by company claims and academic benchmarks.

“Our opening position is skepticism, specifically, skepticism that a fully fault-tolerant quantum computer with a sufficient number of logical qubits can ever be built,” DARPA program manager Joe Altpeter said when launching the initiative last year, the team reports.

That skepticism is now shaping capital allocation. According to the post, DARPA’s decision to advance 11 companies from conceptual design review into the more demanding Stage B of the program is being treated by investors as a meaningful signal. Stage B participants will face closer scrutiny of whether their approaches can deliver “utility-scale operation,” defined as computations whose value exceeds their cost, by 2033.

Architecture Matters Again

The analysts write that this external filtering has powered a shift away from broad, modality-agnostic enthusiasm toward more selective architectural bets. Neutral atoms, trapped ions and superconducting systems continue to attract capital, but there’s also growing investor interest in silicon spin qubits, a platform the firm says it is now backing directly for the first time.

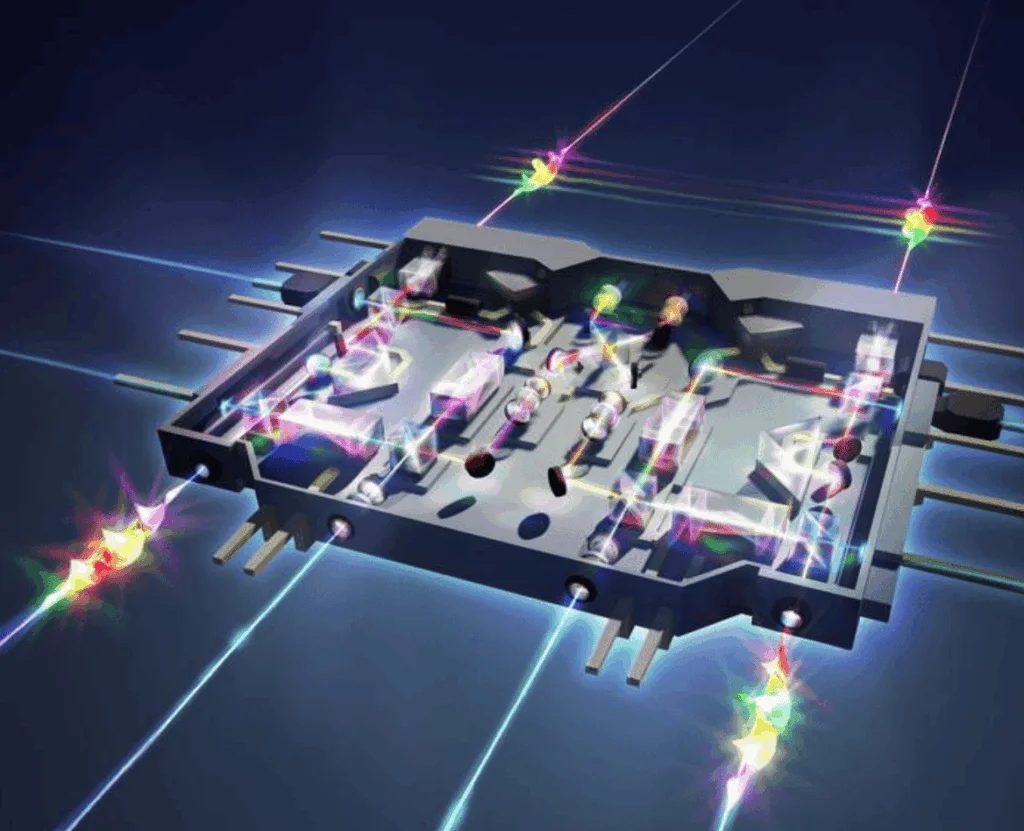

Silicon spin qubits encode information in the spin of individual electrons confined within quantum dots etched into silicon. These structures, often described as “artificial atoms,” are controlled by nanoscale electrodes similar to those used in conventional transistors. The appeal, according to DCVC, lies in two factors: scale and compatibility.

Silicon spin qubits are far smaller than many competing qubit types, potentially allowing far denser integration. They can also be fabricated using modified versions of existing CMOS manufacturing processes, offering a plausible bridge between today’s semiconductor fabs and future quantum processors.

The post identifies London-based Quantum Motion, Finland’s SemiQon, and Sydney-based Diraq as examples of companies pursuing this approach. The team cautions, however, that silicon’s promise does not eliminate the underlying engineering challenges, including noise control, fabrication variability and system integration.

Error Rates, Not Qubit Counts

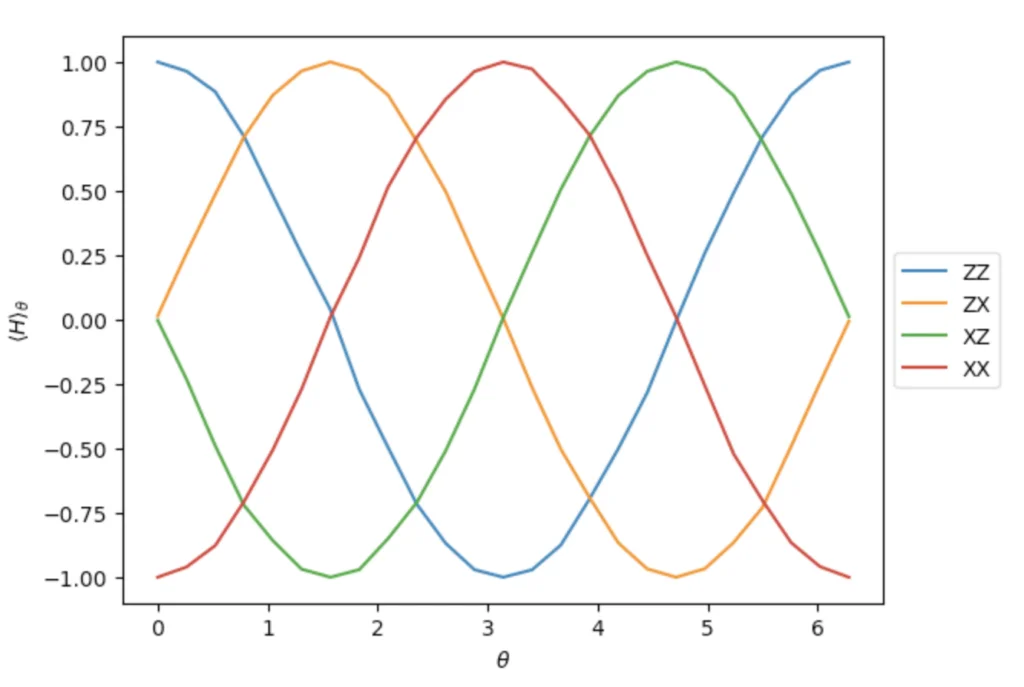

A recurring theme in the post is the idea that the industry’s fixation on qubit numbers is giving way to a more sober focus on error rates and fault tolerance. High-fidelity operations and longer coherence times — the duration over which qubits maintain their quantum state — are presented as more meaningful indicators of progress.

In that context, for example, continued advances by Atom Computing, which combines large-scale neutral-atom arrays with software developed in partnership with Microsoft, and IonQ, which recently demonstrated 99.99 percent fidelity between two trapped-ion qubits.

DCVC report the milestone is a step toward suppressing error rates to levels required for fault-tolerant machines—systems capable of running long computations without being overwhelmed by noise.

Reducing the number of physical qubits needed to create a reliable logical qubit is another area drawing investor attention. The post highlights Iceberg Quantum, a Sydney-based startup developing new architectures based on low-density parity-check codes. By improving error correction efficiency, the company aims to allow hardware developers to do more with fewer qubits.

According to DCVC, the emergence of companies focused primarily on error correction and architectural efficiency, rather than qubit fabrication alone, is a sign that the field is maturing.

Beyond Computing and Toward Markets

While quantum computing dominates headlines, the post argues that nearer-term commercial opportunities may lie in sensing, timing, and navigation. DCVC portfolio company Q-CTRL is cited for its work on compact, rugged quantum navigation systems designed to operate in GPS-denied environments, such as aircraft, ships, and submarines.

The firm has also backed Mesa Quantum, which is developing chip-sized sensors and atomic clocks based on vapor-cell technology. These devices aim to deliver high precision at smaller sizes and lower costs, attributes that are critical for early adoption.

Quantum software, while strategically important, is portrayed as a longer-term opportunity. DCVC is an early investor in Horizon Quantum, but the team reports that hardware and enabling infrastructure are likely to see earlier liquidity, given their defensibility and dependence on physical assets.

The post closes by emphasizing that physics alone will not determine winners. Access to materials, customized fabrication processes, and manufacturing scale-up are now part of venture diligence. Even for silicon-based approaches, existing fabs will require retooling to accommodate quantum devices.

“That’s one place where we can step in as needed.” the team writes. “DCVC has a deep roster of partners who have the technical expertise, business experience, and global networks of connections to offer unique assistance to portfolio companies in securing access to manufacturing lines ahead of competitors.”