Insider Brief

- Researchers at Silicon Quantum Computing demonstrated an 11-qubit silicon-based quantum processor that links multiple qubit registers while maintaining error rates compatible with fault-tolerant operation.

- The study shows that nuclear spin qubits in silicon can be connected through electron-mediated links without the performance degradation that typically limits scaling in quantum systems.

- The results support a modular approach to building larger quantum computers, suggesting silicon could provide a practical foundation for scalable, error-corrected quantum machines.

A quantum processor built from precisely placed atoms in silicon has crossed a key threshold, linking multiple groups of qubits together while preserving the performance needed for error correction, according to a new study published in Nature.

Researchers at Silicon Quantum Computing and UNSW Sydney report that they have demonstrated an 11-qubit processor in which two separate registers of nuclear spin qubits are connected through a controllable electronic link, achieving gate fidelities above widely accepted fault-tolerance benchmarks. The result addresses one of quantum computing’s most stubborn problems — how to scale up without quality collapsing — and strengthens the case for silicon as a practical foundation for large, modular quantum machines.

The work shows that adding more qubits does not inevitably mean adding more noise. Instead, the study suggests that carefully engineered connections between small, high-quality quantum modules could provide a viable path toward systems capable of running useful algorithms.

Not Just More Qubits, More Reliable Qubits

Quantum computing has long promised machines that can outperform classical computers on certain tasks, from simulating molecules to optimizing complex systems. But turning that promise into reality has proved difficult. The challenge is not simply building more qubits, the basic units of quantum information, but ensuring they continue to behave reliably as their numbers grow.

Qubits are fragile, storing information in quantum states that are easily disrupted by heat, electrical noise, or interactions with neighboring qubits. In many experimental systems, performance degrades as devices become larger and more interconnected. Errors multiply, coherence times shrink, and control becomes increasingly complex.

The new study tackles this problem head-on by focusing on modularity. Instead of trying to control a large number of qubits all at once, the researchers link together smaller groups — known as registers — that already operate at very high quality.

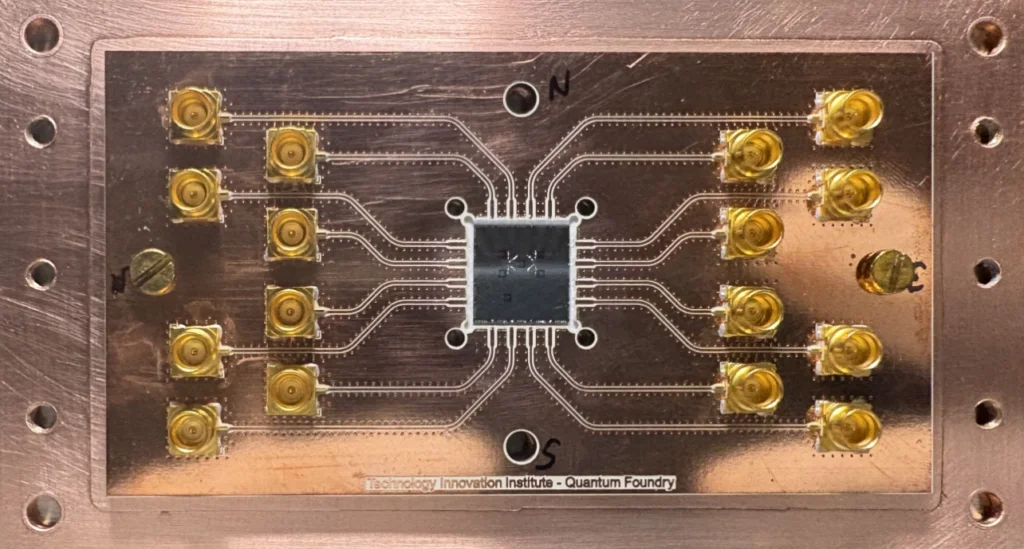

The processor that the researchers described in Nature is built using phosphorus atoms embedded in isotopically purified silicon-28, which is a silicon made almost entirely of the silicon-28 isotope. In this system, each phosphorus atom hosts a nuclear spin that serves as a qubit, behaving like a tiny bar magnet whose orientation can encode information. Nuclear spins are attractive because they are exceptionally stable, retaining quantum information for long periods compared with many other qubit types.

In earlier work, the same research group and others had shown precise control of up to three or four nuclear spin qubits within a single register. What had remained out of reach was a way to connect multiple registers together without sacrificing fidelity.

In this work, the researchers created two registers — one containing four nuclear spin qubits and the other containing five — and connected them using electrons that are shared within each register. These electrons, which also act as qubits, can interact with each other through a mechanism known as exchange coupling. By tuning this interaction with electric gates, the team established a controllable quantum link between the two registers.

The result is an 11-qubit processor with nine nuclear spin qubits used primarily for storing and processing information and two electron spin qubits acting as fast connectors and helpers.

Performance Above Fault-tolerant Thresholds

What sets the result apart is not just the number of qubits, but how well they perform together, the team reports.

According to the study, single-qubit operations achieved fidelities as high as 99.99%, meaning that errors occurred less than once in ten thousand operations for some qubits. Two-qubit operations between nuclear spins reached fidelities of about 99.9%. Operations linking the two registers through the electrons also exceeded 99% fidelity.

These numbers matter because quantum error correction — a variety of techniques to help make quantum computers reliable — demands that error rates fall below specific thresholds. While the exact thresholds depend on the error-correction scheme, values around 99% to 99.9% are commonly cited as necessary for practical fault-tolerant operation.

The researchers also report that these performance levels were maintained even as the system grew more complex. In some cases, metrics improved compared with earlier, smaller devices. That directly counters a long-standing concern in the field that scaling inevitably leads to worse behavior.

The team also demonstrated that any pair of nuclear spin qubits in the processor could be entangled, even if they belonged to different registers. Entanglement is a uniquely quantum phenomenon in which the states of two particles are correlated, regardless of distance. It is a fundamental resource for quantum computing.

Using this connectivity, the researchers prepared a variety of entangled states, including Bell states between pairs of qubits and more complex Greenberger-Horne-Zeilinger, or GHZ, states involving multiple qubits. They showed that genuine multi-qubit entanglement could be sustained across as many as eight nuclear spin qubits.

How It All Works

In the system, the phosphorus atoms are placed into silicon with sub-nanometer precision using scanning tunneling microscopy combined with epitaxial growth. This level of control allows the researchers to design the interactions between atoms almost atom by atom.

Within each register, multiple phosphorus nuclei couple to a single shared electron. That electron serves as an intermediary, allowing operations on one nuclear qubit to influence others. It also enables a form of readout in which information stored in a nucleus is transferred to the electron, which is easier to measure.

To connect the two registers, the electrons in each register are brought close enough that they can interact through exchange coupling. By adjusting voltages on nearby gates, the strength of this interaction can be tuned. The researchers operated in a regime where the coupling was strong enough to enable fast operations but weak enough to avoid unwanted interference.

Controlling such a system requires managing dozens of microwave frequencies, each corresponding to a specific transition of a specific qubit. One potential obstacle is that the number of required calibrations grows rapidly as more qubits are added. The study addresses this by showing that frequency shifts within a register occur collectively, allowing the system to be recalibrated efficiently with only a small number of measurements.

This scalable calibration strategy is an underappreciated part of the result. Without it, even a high-quality device would be impractical to operate as it grows larger.

Why Silicon Matters

The study also suggests some broader implications that crosses technological fields. Silicon is the foundation of the modern electronics industry, with decades of investment in manufacturing, design and supply chains. A quantum computing platform that can leverage that infrastructure would be viewed as especially attractive.

Many leading quantum approaches rely on materials or techniques that are difficult to integrate into existing chip-making processes. Superconducting qubits require complex cryogenic wiring and microwave control, for example, and tapped ions and neutral atoms demand elaborate vacuum and laser systems.

The phosphorus-in-silicon approach uses only two elements and avoids metal control structures near the qubits. According to the researchers, this simplicity reduces sources of noise and crosstalk, while also pointing toward eventual compatibility with industrial-scale fabrication.

The work does not claim that silicon-based quantum computers are close to commercialization.

The processor operates at temperatures near absolute zero, and scaling from 11 qubits to the thousands or millions needed for useful applications remains a major challenge. Still, the demonstration strengthens the argument that silicon can support not just individual qubits, but interconnected systems with the performance needed for error correction.

Limits and open questions

Despite its advances, the study also highlights the work that will be needed in the future.

The processor relies on post-selection in some experiments, meaning that certain measurements are discarded to ensure that qubits start in the desired states. While useful for research, post-selection is not viable in a full-scale machine.

The experiments also involve careful tuning and optimization that would need to be automated and made more robust in a larger system. Crosstalk between control signals, frequency crowding, and variability in atomic placement all pose challenges as more registers are added.

Another open question is speed. Nuclear spin qubits are exceptionally stable, but they are generally slower to manipulate than some other qubit types. The use of electron spins as fast ancilla qubits helps mitigate this, but future architectures will need to balance stability, speed, and complexity.

While the study demonstrates connectivity and entanglement, it does not yet implement full quantum error-correction protocols across multiple registers. Doing so will be a critical next step in translating high-fidelity components into a fault-tolerant system.

The researchers outline several directions for future work, including improving pulse control, reducing residual noise, and applying more comprehensive benchmarking techniques to better understand error sources. They also point toward extending the architecture to include more registers, testing whether the linear scaling of calibration and control can be maintained.

For the broader quantum community, the work reframes the scaling debate. Instead of asking how quickly any one platform can reach large qubit counts, it emphasizes the quality of connections between smaller, reliable units. That modular approach mirrors how classical computing systems evolved, from individual transistors to integrated circuits and networks of processors.