Insider Brief

- A study by researchers at IonQ and Aalto University finds that distributed quantum computers built from multiple linked processors can outperform a single larger machine, even when the connections between processors are relatively slow.

- Using simulations of realistic, intentionally conservative hardware conditions, the researchers show that carefully designed modular architectures can achieve lower error rates and shorter execution times than monolithic systems for certain classes of quantum circuits.

- The results suggest that scaling quantum computers through modular designs may be viable in the near term, without waiting for major advances in ultra-fast quantum networking, though the advantage demonstrated is architectural rather than a claim of classical–quantum supremacy.

- Photo by geralt on Pixabay

Quantum computers built from many smaller machines that are linked together can outperform a single large processor even when the connections between them are slow, according to a study by researchers at IonQ and Aalto University.

The researchers’ findings challenge a common assumption in the field that sluggish quantum links erase the benefits of modular, networked quantum systems. Instead, the study reports that carefully designed distributed architectures can achieve lower error rates and faster execution than standalone machines under realistic hardware constraints. The team reports this opens a plausible near-term path to scaling quantum computers without waiting for ultra-fast quantum networks.

“Our numerical simulation proves that distributed CliNR can achieve simultaneously a lower logical error rate and a shorter depth than both the direct implementation and the monolithic CliNR implementation of random Clifford circuits,” the team writes.

Scaling Quantum

The study addresses the ability to scale quantum systems, which is considered one of the central engineering problems in quantum computing. Many researchers believe that practical quantum applications will require machines with millions of quantum bits, or qubits. Building a single processor at that scale is widely seen as unrealistic with today’s technology. As a result, companies and national labs have increasingly turned to modular designs, which means multiple quantum processing units, or QPUs, that are linked together.

The obstacle has been the link itself because connecting QPUs requires generating entanglement — a fragile quantum correlation — between machines. In today’s systems, it can take milliseconds to create this entanglement, while operations inside a single QPU take microseconds or less. That mismatch has led many researchers to assume that distributed quantum computing will stall as machines wait for entanglement to arrive.

The researchers argue that this assumption is incomplete and show that, for certain classes of quantum circuits, a network of smaller QPUs linked by relatively slow connections can outperform a single larger processor running the same task. The study tests this claim using a realistic — and deliberately pessimistic — model of distributed quantum hardware to see whether any advantage survives under unfavorable conditions.

The Secret of Distributed Systems

Quantum operations are noisy, and errors grow as circuits become deeper, in other words, they require more sequential steps. One way to manage this problem is to redesign circuits so that error-prone sections can be checked, discarded and retried before they corrupt the main computation.

The study builds on a recently developed technique known as Clifford noise reduction, or CliNR. CliNR applies to a large and important class of quantum circuits called Clifford circuits, which play a central role in quantum error correction and benchmarking, among other quantum advantage experiments. Instead of running an entire circuit in one go, CliNR breaks it into smaller subcircuits. Each subcircuit is prepared and verified in advance. If verification fails, it is simply redone, preventing faulty pieces from contaminating the final result.

In a traditional, monolithic quantum computer, all of this happens on a single processor. However, in the IonQ-led study, researcher proposes a distributed version of CliNR, where different QPUs prepare and verify different subcircuits in parallel. Only at the final stage are the results stitched together, using entanglement between machines.

This structure turns the usual disadvantage of slow links into something manageable. Most of the work, including the deepest and noisiest parts of the circuit, is done locally on each QPU, without consuming any entanglement. The quantum links are only required during short “injection” steps, when verified subcircuits are combined.

According to the study, this approach allows entanglement to be generated in the background, during earlier preparation stages. As a result, the system often avoids waiting for links altogether, even when entanglement generation is several times slower than local quantum gates.

Simulation Results Under Realistic Assumptions

To test the idea, the researchers ran detailed circuit-level simulations comparing three approaches: a direct implementation on a single QPU, a monolithic CliNR implementation on one larger QPU, and a distributed CliNR implementation spread across multiple QPUs.

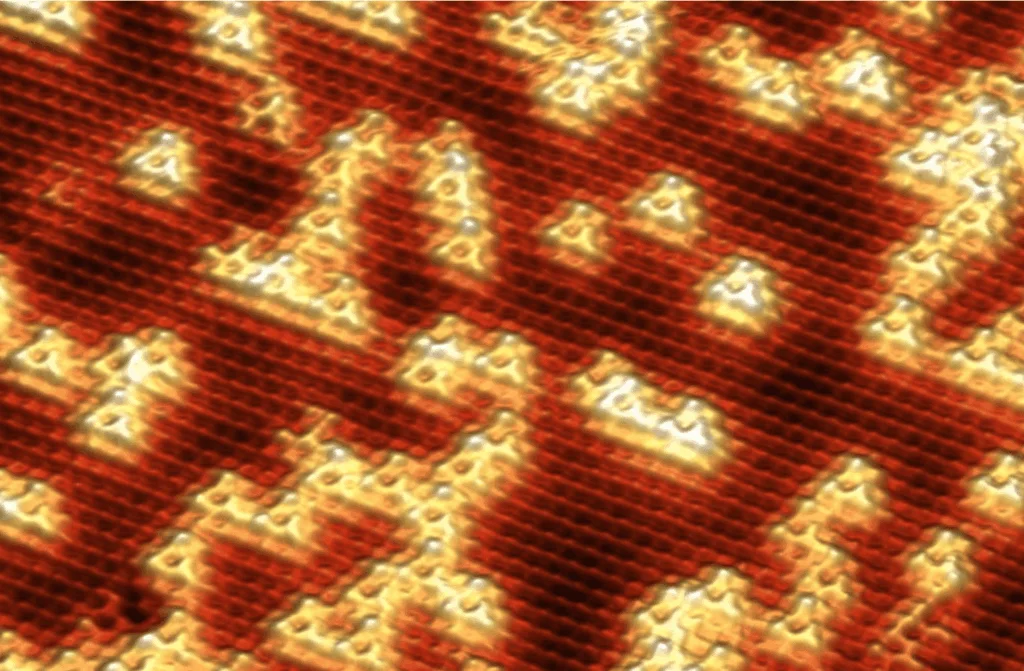

The simulations focused on random Clifford circuits with up to 100 qubits — a scale that is challenging but within sight for near-term hardware. Noise rates were chosen to reflect recent experimental results in trapped-ion systems, where two-qubit gate error rates near one part in ten thousand have been reported.

In one set of simulations, the researchers fixed the entanglement generation time to be equal to the local gate time and varied the number of qubits. They found that the distributed approach achieved logical error rates comparable to monolithic CliNR, while requiring significantly less circuit depth. In some cases, the distributed version even ran with less depth than the direct, non-CliNR implementation.

In another set of simulations, the team fixed the circuit size and gradually slowed down entanglement generation. The team found that even when generating entanglement took up to five times longer than local gate operations, the distributed system maintained both lower error rates and shorter depth than the monolithic alternatives. Only when links became much slower did the advantage begin to fade.

These results suggest that distributed quantum computing is not merely a long-term aspiration dependent on breakthroughs in quantum networking. Under the right algorithmic structure, it can offer concrete performance benefits with today’s or near-term interconnect speeds.

Implications for Quantum Hardware Strategy

The findings carry implications for how quantum computers may be built and scaled over the next decade. Many leading platforms — including trapped ions, neutral atoms, and photonic systems — are already modular by nature. For these technologies, scaling often means linking separate traps, arrays, or chips rather than enlarging a single device.

The study provides a quantitative argument that such modular strategies can pay off sooner than expected. It also suggests that quantum networking efforts need not achieve parity with local gate speeds to be useful. Even relatively slow links, if used sparingly and strategically, can enable better overall system performance.

For companies like IonQ, which has emphasized modular trapped-ion architectures, the work offers theoretical support for an approach already reflected in product roadmaps. More broadly, it aligns with growing public investment in quantum interconnects, including government programs aimed at building quantum networks alongside quantum processors.

Future Work

While the study points towards optimistic outcomes, the researchers are careful about the scope of the work. The demonstrated advantage applies to Clifford circuits, not to arbitrary quantum programs. While Clifford circuits are central to many tasks — including error correction, calibration and some quantum advantage experiments — they would not, by themselves, lead to universal quantum computing.

The results are also based on simulations rather than hardware experiments, which are likely next steps. Although the noise models are grounded in experimental data, real systems can behave in unexpected ways, particularly when multiple QPUs and links are involved.

In addition, the distributed architecture analyzed in the study is deliberately simple. Each QPU is connected to only two neighbors in a ring topology, and each link produces at most one entangled pair at a time. While this strengthens the claim that the advantage survives under harsh constraints, it also means that practical implementations may require careful engineering to match the model’s assumptions.

Finally, it’s important to understand that the advantage is architectural rather than absolute. The study does not claim that the distributed system outperforms classical computers on these tasks. Instead, it shows that a distributed quantum machine can outperform a monolithic quantum machine running the same algorithm under the same noise conditions.

Looking ahead, the researchers list specific experiments that could test their ideas on real hardware. In particular, they highlight a class of circuits known as conjugated Clifford circuits, which are believed to be difficult for classical computers to simulate. Implementing such circuits using distributed CliNR could form the basis of a quantum superiority experiment carried out across multiple linked QPUs.

The study also explores asymptotic behavior, asking what happens as the number of QPUs grows. In that regime, the researchers show that avoiding performance bottlenecks does not require links to scale with the total number of qubits. Instead, the number of parallel entanglement channels needs to grow only modestly with the number of modules, independent of how large each module becomes.

Future work could refine the protocol further, reducing circuit depth by running multiple verification attempts in parallel or by restructuring how subcircuits are divided across machines. Advances in quantum networking — such as improved photon collection, better quantum memories, or faster link hardware — could widen the gap between distributed and monolithic designs.

The team included Evan E. Dobbs, Nicolas Delfosse and Aharon Brodutch, all of IonQ. Dobbs is also affiliated with Aalto University.

For a deeper, more technical dive, please review the paper on arXiv. ArXiv is a pre-print server, which allows researchers to receive quick feedback on their work. However, it is not — nor is this article, itself — official peer-review publications. Peer-review is an important step in the scientific process to verify results.