Insider Brief

- Quantum Research Sciences says it is applying quantum optimization tools to help prevent parts shortages, using quantum systems to evaluate sourcing options, inventory needs, and supplier risk faster than classical methods.

- The company pairs AI-based early-warning models with quantum engines that calculate optimal mixes of replacement parts, suppliers, and lead-time strategies — an approach now being tested with the Defense Logistics Agency.

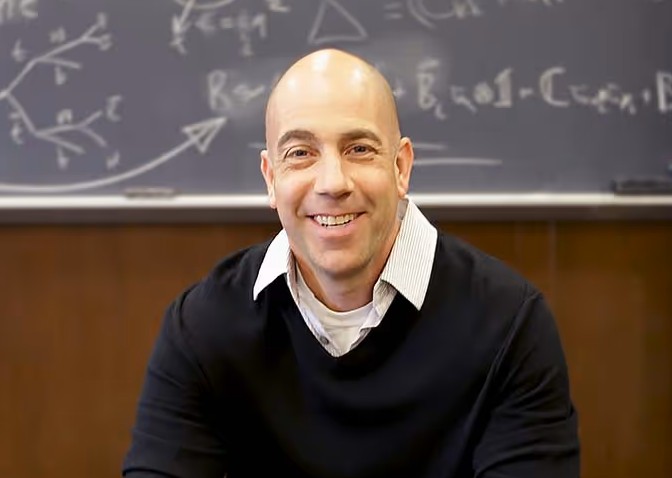

- CEO Ethan Krimins argues that logistics and supply-chain optimization offer near-term commercial use cases for quantum computing, contrasting them with more hardware-intensive applications like molecular simulation that remain further from deployment.

How can quantum computing help keep a decades-old U.S. military bomber flying?

It may seem like an unusual application for a quantum computer, which to many people still sounds like a science that is years away from practical use, but Quantum Research Sciences CEO Ethan Krimins said in an interview with The Quantum Insider that the quantum software startup is already using it to help keep aging military aircraft flying and critical weapons systems operating.

“Our team has worked very hard at developing applications that can be operationalized,” Krimins said. “People use the words practical, useful. I actually prefer the word operational, but regardless of the focus area there is a lot of exciting technology that’s going on in the quantum world.”

Krimins said his team is focused on the goal of turning quantum science from a lab curiosity into an operational tool for logistics, sourcing and asset management. Speaking ahead of his talk at this week’s Q2B Silicon Valley quantum conference, he argued that optimization problems in supply chains are a clear commercial beachhead for the technology and that early projects with the Air Force and Defense Logistics Agency show it can deliver results today.

Quantum as a Faster Calculator

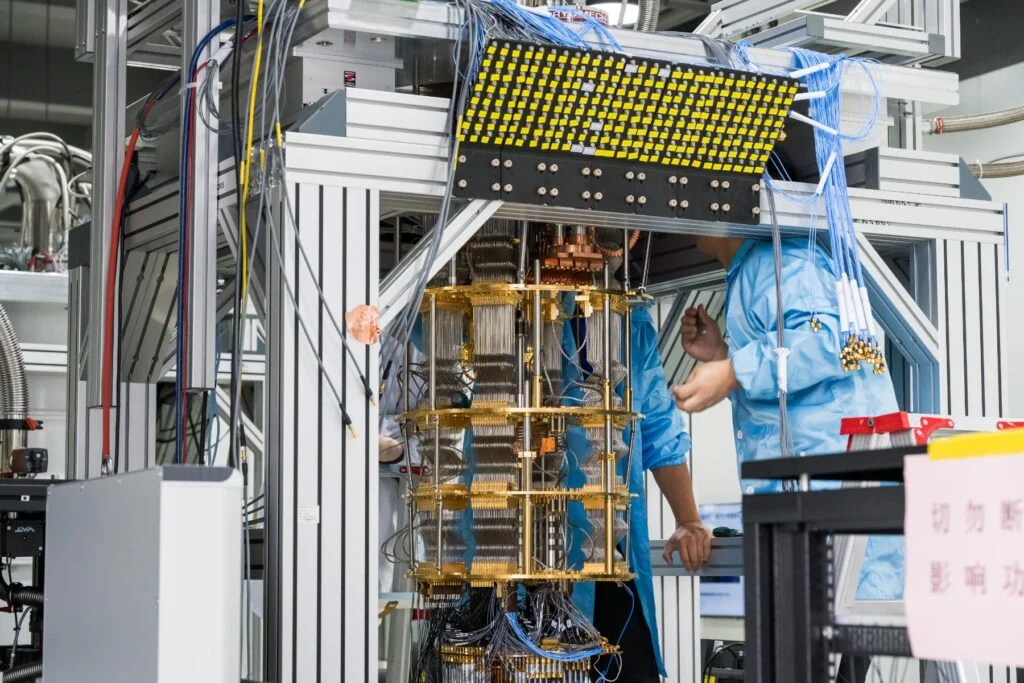

Krimins describes a quantum computer as a high-level, faster, more specialized calculator. It takes in data and returns an answer to a narrowly defined problem.

“A quantum computer can take many factors and numerous associated criteria that we ordinarily could not compute with a classical computer” Krimins said. “And it just very quickly does that computation to generate an answer.”

The value of that speed becomes more obvious inside a military logistics network. Krimins points to the Defense Logistics Agency (DLA). Some parts being managed by DLA sit on the shelf for many years. The companies that made the original components may be out of business. The tools and drawings used to manufacture them may be lost or sitting in archives.

Logisticians are still expected to keep the platforms that need those parts mission-ready. When a rarely used part finally fails, they must figure out where to source a replacement, whether they can manufacture it or if they need to redesign it entirely. Each option has different costs, lead times and risks.

According to Krimins, this is where quantum optimization fits neatly. His team uses data on suppliers, historical orders, costs and timelines to build models of the choices available for each problematic part. The quantum system then evaluates which mix of suppliers and strategies best meets availability, cost and readiness goals. The objective is not to replace human judgment, he says, but to give decision-makers a concrete, data-backed starting point.

The promise, he said, is not that these systems “predict” the future, but that they can search through far more options than a classical computer in the time available and point to an optimal choice for decision-makers.

He said that there is nothing ambiguous about this. The machine is not “deciding” what to do in the way an AI assistant might. It is performing a defined computation and surfacing an answer to a math problem that humans cannot solve quickly enough on their own.

According to Krimins, most business leaders approach decisions such as choosing suppliers or stocking parts with a mix of spreadsheets, experience and shortcuts. Humans and traditional computers struggle when the variables explode: multiple suppliers, different prices, changing lead times, contract terms, reliability scores and risk factors.

In practice, that complexity forces people to use rough scoring systems or heuristics. They rate vendors red, yellow or green, or they assign simple scores to factors and hope those rankings are close enough. Krimins called it an educated guess.

Quantum systems, by contrast, can ingest the exact data — specific lead times, precise prices, detailed risk measures — and treat each supplier and constraint as part of a large, very complex math equation. The machine then searches the space of possible combinations and returns an answer that respects all those constraints and trade-offs. Classical computers can, in theory, do the same thing, but for some problems the search could take centuries, Krimins said.

Quantum computing makes those particular “combinatorial optimization” problems tractable on a useful timescale, he added.

For the Defense Logistics Agency, which he likens to “the Amazon for the federal government,” the challenge is knowing which parts and suppliers are drifting toward obsolescence.

Today the agency is often forced to operate reactively, Krimins said. An engineer reaches for a part and finds an empty shelf. Support staff then scramble to place an order. In the worst cases, they discover the supplier went out of business years ago. That triggers a long chain of work: finding or rebuilding drawings, recreating or fabricating tooling and qualifying a new manufacturer. The entire process can delay availability for a year or more, with direct implications for readiness.

Quantum Research Sciences is building a two-stage system to push that work earlier in time. First, an AI layer pulls in data from commercial and government sources such as credit reports and federal contracting databases.

“We’re taking all this data in to get an early warning – using AI – that the supplier or that part might be at risk of obsolescence,” Krimins pointed out. “And then once we have that list of ‘at-risk’ suppliers, we then start using the quantum technology to identify how many parts need to be on the shelf and when.”

Krimins says this pairing of AI for pattern detection and quantum for optimization illustrates how the two technologies can complement each other rather than compete. The AI surfaces weak signals in messy, real-world data; the quantum engine then crunches clean numbers to suggest specific actions, he said.

Two Tracks of Quantum — And Two Timelines

In the broader quantum field, Krimins sees two main tracks. The first is the optimization work his company pursues: taking many variables and constraints and finding the best answer. The second is simulation — using quantum systems to model molecules and chemical reactions more comprehensively than classical computers allow.

Simulation is the branch that grabs headlines, promising breakthroughs such as new drugs, better materials and longer-lasting batteries, Krimins said.

With optimization, the problems are cleaner, the math is better understood and the hardware requirements are less extreme. That is why he is betting his company on logistics, sourcing and related fields. They offer concrete use cases where quantum tools can, in his words, “solve things that cannot be solved other ways” with current systems.

“Logistics is at the nexus of finance, operations, engineering and strategy, and you can see all these business operations coming together,” Krimins added. “I know it doesn’t sound very exciting, but inventory management, sourcing, supply chain management and logistics are the heart of a successful enterprise and so it’s given us, as well as people outside of the, the quantum realm, a front row seat into what’s taking place operationally.”