Insider Brief

- A UCLA study reports that an asymmetric SQUID-based superconducting diode can create directional quantum gates and steer entanglement, suggesting a path to smaller and more efficient quantum processors.

- The device embeds nonreciprocity directly into superconducting hardware by using a flux-biased, asymmetric SQUID to produce direction-dependent frequency shifts, one-way qubit interactions and selective Bell-state generation.

- The findings indicate that chip-level nonreciprocity could reduce reliance on bulky off-chip isolators and circulators, potentially simplifying wiring, improving signal routing and enabling more scalable superconducting quantum systems.

A new study reports that a simple superconducting diode can create directional quantum gates and steer entanglement between qubits. If it scales, it could lead to the development of smaller, more efficient quantum processors.

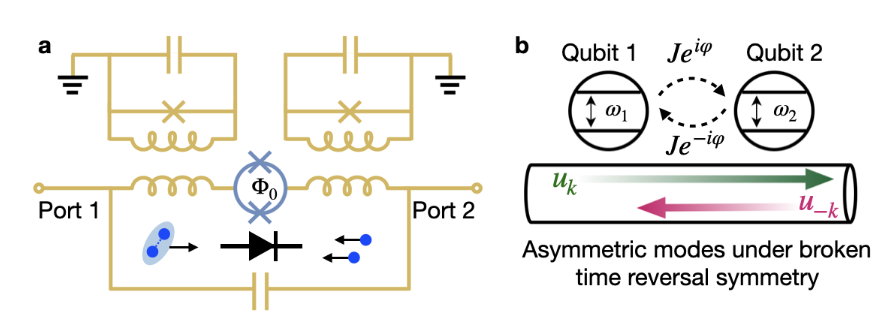

In the pre-print server arXiv , a UCLA research team describe a superconducting device that uses an asymmetric SQUID — which is a loop built from a superconducting device made of two superconductors separated by a thin barrier, called Josephson junctions — to control the direction of quantum signals using a single magnetic-flux line. The team reports that this diode can shift a resonator’s frequency depending on signal direction, induce one-way interactions between qubits and create Bell states selectively.

The team’s findings suggest that a hardware-based approach to nonreciprocity — or, the ability to treat signals differently depending on the direction they travel — could make it easier to route signals and protect qubits without the bulky components found in today’s machines. They add that this could lead to more scalable quantum systems.

The researchers report that superconducting quantum computers rely on precise control of microwave signals that move between qubits, resonators and supporting electronics. To prevent noise from flowing backward into fragile qubits, current systems use ferrite circulators and isolators. These devices can be larger than the chips themselves and must be mounted off-chip inside cryogenic refrigerators, limiting how many qubits can be interconnected. The UCLA team indicates that eliminating these components by embedding nonreciprocity directly in the hardware could streamline future quantum processors.

The researchers say their superconducting diode offers a compact, coherent way to introduce that behavior. Rather than depending on magnetic materials or active modulation, the asymmetric SQUID produces direction-dependent behavior from the structure of the superconducting state itself, enabling what the authors describe as device-level nonreciprocity.

The team builds the superconducting diode from a SQUID in which the two Josephson junctions have different transmission properties. When the loop is biased with magnetic flux, the junctions respond asymmetrically, breaking the usual symmetry between forward and backward currents. This gives the device a direction-dependent critical current — the maximum supercurrent it can carry — and shifts the resonator’s inductance in response to the direction of applied current. Those shifts change the resonator’s frequency in measurable ways.

In the study, the authors show how this behavior leads to two distinct resonance frequencies, one for each direction. They model the device’s transmission using standard circuit techniques and calculate how the two-port scattering parameters differ depending on whether microwaves travel forward or backward. The team reports frequency differences on the order of tens of megahertz using typical circuit parameters, enough to distinguish the two directions clearly. The researchers attribute this behavior to third-order nonlinearities in the Josephson energy landscape, which become active when the device is flux-biased and the symmetry between the two junctions is broken.

To track these effects, the authors derive the diode’s transmission spectrum with input-output theory, a technique used widely in circuit quantum electrodynamics. The model predicts resonance peaks that shift depending on the transmission direction, producing an asymmetry that persists even when the diode is driven off resonance. The team also identifies a ratio that expresses the strength of nonreciprocity and shows that the effect remains sizable over a broad frequency range.

Direction-Selective Qubit Coupling

With the device behavior established, the researchers incorporate the diode into a circuit containing two qubits. When the qubits couple to the resonator mediated by the diode, they no longer interact through symmetric channels. Instead, the effective coupling between them acquires a complex phase. This phase produces nonreciprocal interactions in which the transfer of quantum excitation depends on which qubit is excited first.

According to the study, this behavior shows up in population dynamics. When the diode phase is set to zero, the energy exchange between qubits is even and produces identical time traces regardless of the initial state. But when the phase shifts to nonzero values, the system becomes directional. Pulse simulations show that excitation flows preferentially in one direction, echoing how an electrical diode allows current to flow easily one way but not the other. At the same time, dissipation can either enhance or weaken this bias depending on its relative strength, a behavior the authors analyze using a standard master equation that models open quantum systems.

The research team then uses this interaction to implement a directional half-iSWAP gate, an entangling operation common in superconducting architectures. When only one qubit is excited at a time, the gate produces a superposition of states with a phase that depends directly on the diode’s nonreciprocal coupling. When the phase reaches specific values, the system produces standard Bell states. The authors simulate how the concurrence — a measure of entanglement strength — evolves depending on which qubit is prepared in the excited state, and report strong asymmetry when the diode is configured for nonreciprocal coupling.

In addition to the gate dynamics, the researchers simulate full two-qubit state tomography at the midpoint of the iSWAP interaction. The reconstructed quantum states confirm that the entangled states vary predictably with the diode phase and in some cases show directional suppression or enhancement of the Bell-state components when dissipation is included. The study strongly suggests that this ability to shape entanglement pathways with a single control parameter could support new types of multi-qubit gates and routing schemes.

These findings carry implications for building larger superconducting processors. Today, systems from IBM, Google and academic groups depend heavily on directional microwave components mounted outside the chip. These isolators and circulators take up volume inside dilution refrigerators and limit how many qubits and control lines can be routed to the coldest stage. The UCLA team suggests that a built-in diode could reduce this footprint by introducing nonreciprocal behavior directly in the chip layout. Because the effect is passive and controlled by a single flux bias, the design could reduce wiring complexity, simplify interconnects and improve the reliability of routing signals between qubits.

The researchers also point out that directional coupling could help prevent unwanted back-action between qubits, lowering the chance that operations on one qubit disturb another. According to the team, embedding phase-tunable, nonreciprocal couplers could help construct modular architectures in which clusters of qubits communicate through controlled channels. Beyond processors, the study says many-diode networks could emulate synthetic gauge fields, enabling controlled movement of quantum states along preferred pathways, a feature relevant to quantum simulation and long-distance quantum links.

Methods and Modeling Choices

Most of the study relies on theoretical modeling supported by measured parameters from typical superconducting circuits. The authors derive the diode response by expanding the Josephson potential around its minimum and show how third-order terms generate direction-dependent shifts. They model the transmission response using classical input-output theory but also validate the dynamics using Heisenberg-Langevin equations and numerical time evolution for the qubit populations. State tomography is produced through simulated measurement protocols following standard computational bases.

The work does not report measurements from fabricated devices, instead relying on realistic parameters to show experimental feasibility. The researchers acknowledge that dissipation remains necessary to translate the diode’s nonreciprocity into population and entanglement dynamics, because the device operates passively. In practice, the strength and placement of dissipative channels would need to be engineered carefully to realize full isolation without degrading qubit coherence.

Future Directions

The researchers identify several next steps. They point to the need for device optimization and experimental realization of the diode within a superconducting circuit. They also highlight the importance of characterizing coherence properties, since any added nonlinearity or control line could introduce noise. Simulating larger lattices of qubits interconnected with diodes is another area the team says will be important, particularly for testing whether directional couplers can reduce error rates in error-corrected systems.

Integrating superconducting diodes directly onto chips could ultimately change how quantum processors are built, according to the team. If successful, the approach could eliminate some of the hardware overhead now required for routing and protecting signals, making it easier to scale systems into the hundreds or thousands of qubits. The study positions the diode as a foundational component for directional state transfer, selective entanglement generation and quantum network design, which are areas that will become more important as superconducting machines expand in size and complexity.

The research team included Nicolas Dirnegger, Prineha Narang and Arpit Arora.

For a deeper, more technical dive, please review the paper on arXiv. It’s important to note that arXiv is a pre-print server, which allows researchers to receive quick feedback on their work. However, it is not — nor is this article, itself — official peer-review publications. Peer-review is an important step in the scientific process to verify results.