Insider Brief:

- The true nature of black holes remains elusive due to their lack of electromagnetic emissions. Scientists rely on gravitational waves to study them, using advanced detectors like LIGO and Virgo.

- The increasing volume of gravitational wave detections is straining classical data analysis methods. As third-generation detectors such as Cosmic Explorer and Einstein Telescope come online, scientists must develop more efficient computational techniques.

- Researchers from the Complutense University of Madrid, the Polytechnic University of Madrid, and Queen Mary University of London developed QBIRD, a hybrid quantum algorithm designed to improve gravitational wave parameter estimation. Through quantum walks and renormalization techniques, QBIRD reduces computational complexity while maintaining accuracy.

- QBIRD successfully inferred key parameters such as chirp mass and mass ratio from simulated black hole merger data, demonstrating its potential to enhance gravitational wave astronomy. While current implementations are limited by classical simulations of quantum algorithms, full-scale deployment on quantum hardware could enable even better analysis in the future.

Once confined to the margins of a notebook as a mere scribble, black holes were long regarded as little more than a mathematical curiosity. Today, they stand among the most profound and unsettling discoveries in modern physics. Once thought to be purely theoretical constructs, black holes are now the focus of intense scientific investigation, yet what we know about them remains frustratingly incomplete.

One of the biggest challenges in understanding black holes is that they emit no light, making them effectively invisible. But while we cannot see them, we can listen to them. When two black holes merge, they send out ripples in spacetime—gravitational waves—that can be detected by instruments like LIGO and Virgo. However, the volume of data generated by gravitational wave detections is expected to surge dramatically, overwhelming traditional methods of analysis.

A recent study from researchers at the Complutense University of Madrid, the Polytechnic University of Madrid, and Queen Mary University of London introduces QBIRD, a hybrid quantum algorithm designed to infer gravitational wave parameters more efficiently than classical methods. Through quantum techniques, the researchers hope to resolve one of the most pressing challenges in gravitational wave astronomy: how to rapidly and accurately extract meaningful information from an increasing flood of detections.

LISTENING TO THE SILENT MERGERS OF BLACK HOLES

Black hole mergers are cataclysmic events; they are titanic collisions that send ripples across the fabric of spacetime. Unlike supernovae or gamma-ray bursts, these events do not produce electromagnetic radiation, meaning no visible light, X-rays, or radio waves reach us. Instead, they announce their presence through gravitational waves.

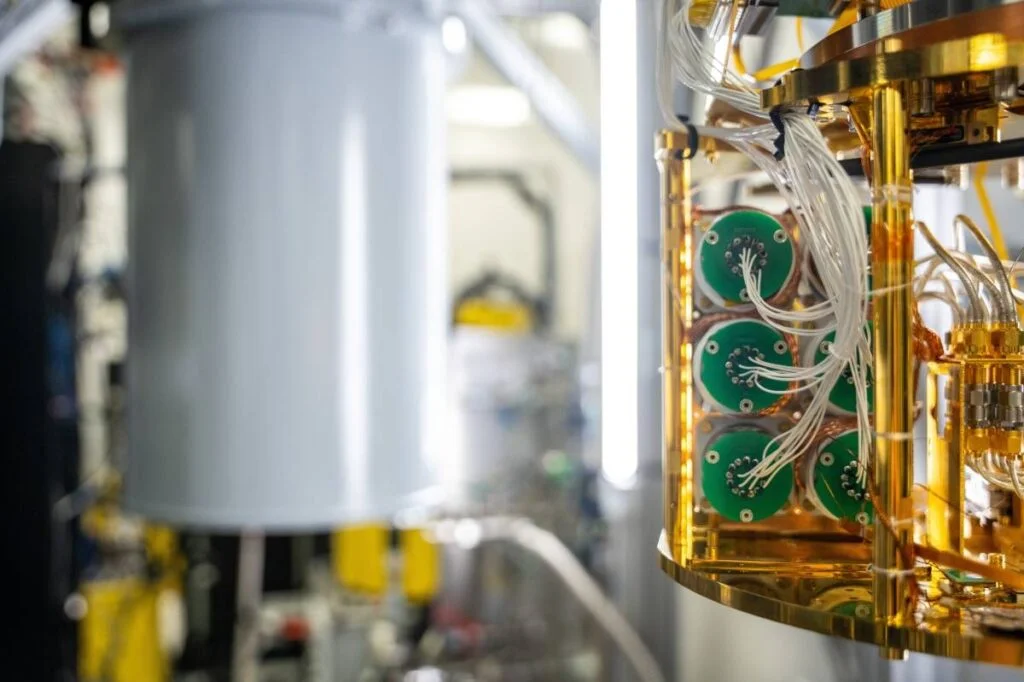

Detecting these waves requires precision instruments known as gravitational wave interferometers, such as LIGO and Virgo, which are colossal observatories capable of measuring fluctuations in spacetime thousands of times smaller than a proton. The coming generation of detectors, including the Cosmic Explorer and Einstein Telescope, will expand our ability to detect and analyze these waves.

However, this progress brings new challenges. As detection rates increase from dozens to thousands of gravitational wave signals per day, scientists must find a way to process and extract meaningful information from an unprecedented amount of data. Traditional computational techniques, while powerful, are quickly approaching their limits.

WHAT QBIRD HEARD

The research team behind QBIRD proposes a new approach to gravitational wave data analysis, using quantum techniques to enhance the efficiency of parameter estimation. To understand why this matters, consider Bayesian inference—a statistical method that updates our understanding of an event as new data comes in. In gravitational wave astronomy, Bayesian inference is essential for estimating parameters such as the mass, spin, and distance of merging black holes. Classical methods rely on computationally expensive techniques such as Markov Chain Monte Carlo (MCMC), which systematically explore the vast parameter space to determine the most likely physical properties of the source.

Unlike classical MCMC, which requires a large number of iterative steps to converge on a solution, QBIRD uses a quantum-enhanced Metropolis algorithm that incorporates quantum walks to explore the parameter space more efficiently. Instead of sequentially evaluating probability distributions one step at a time, QBIRD encodes the likelihood landscape into a quantum Hilbert space, allowing it to assess multiple transitions between parameter states simultaneously. This is achieved through a set of quantum registers that track state evolution, transition probabilities, and acceptance criteria using a modified Metropolis-Hastings rule.

Additionally, QBIRD incorporates renormalization and downsampling, which progressively refine the search space by eliminating less probable regions and concentrating computational resources on the most likely solutions. These techniques enable QBIRD to achieve accuracy comparable to classical MCMC while reducing the number of required samples and computational overhead, making it a more promising approach for gravitational wave parameter estimation as quantum hardware matures.

The study applied QBIRD to gravitational wave signals from binary black hole mergers, focusing on two key parameters. Chirp mass, which describes how two orbiting objects spiral inward before merging, helps determine the frequency evolution of the gravitational wave signal. Mass ratio, which represents the relative size of the two merging objects, influences the waveform’s amplitude and asymmetry. According to the study, by accurately estimating these parameters, QBIRD helps characterize the properties of black hole mergers with precision comparable to classical methods.

In simulated cases, QBIRD accurately recovered these parameters, matching the precision of classical Bayesian inference methods while requiring fewer computational resources. This suggests that quantum techniques may not only match but potentially outperform classical techniques as quantum hardware matures. However, the current implementation of QBIRD is constrained by the limitations of simulating quantum algorithms on classical hardware. Full-scale execution on a functional quantum processor would might allow for a broader range of gravitational wave parameters to be inferred with unprecedented efficiency.

CHALLENGES AND THE ROAD AHEAD

Despite promising results, quantum computing is not yet at the stage where it can fully replace classical methods in gravitational wave analysis. The biggest hurdle is hardware as current quantum processors still have limited qubits and error rates that make large-scale computations difficult. However, progress is relatively rapid. As quantum hardware improves, algorithms like QBIRD may become essential for analyzing the flood of data from next-generation gravitational wave detectors.

More broadly, QBIRD represents the growing fusion of quantum computing and astrophysics. Black holes, once thought to be purely theoretical, are now objects of precise, data-driven study. The intersection of quantum mechanics, astrophysics, and computation may just hold the answers to some of the most fundamental questions about the universe.

Contributing authors on the study include Gabriel Escrig, Roberto Campos, Hong Qi, and M. A. Martin-Delgado.