Just an hour from New York City, designed by architect Eero Saarinen, is the IBM Think Lab in Yorktown Heights. The lab, home to the IBM Quantum System Two alongside prototype AI chips, is intended to go beyond a collection of modern technologies, but rather, to serve as a physical meeting place for scientists developing the future convergence of computing paradigms.

The Vision Behind the Lab: Where Past Meets Future

In a recent blog post by IBM, readers receive an exclusive glimpse into the intersection of technology and architecture, where Saarinen’s design includes floor-to-ceiling windows permitting light-filled nature breaks and varied workspaces designed to inspire serendipitous meetings between scientists. The goal was to gather interdisciplinary experts under one roof in hopes of sparking innovation. This vision aligns with IBM’s approach to computing, where the lines between different paradigms—bits, neurons, and qubits—are increasingly blurred.

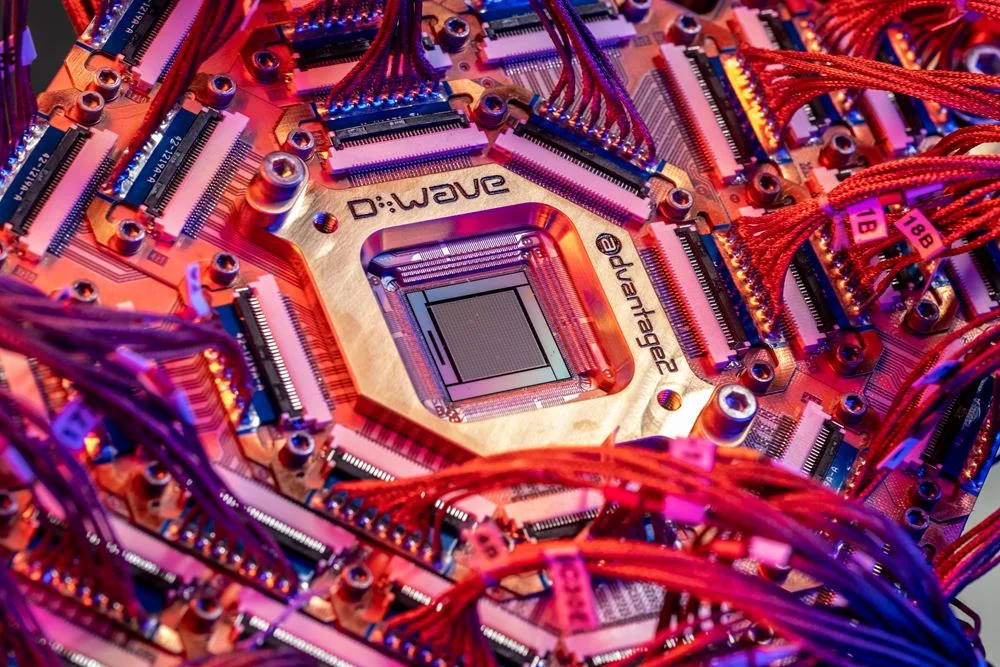

As noted in the post, for decades, the world of computing was driven by a singular goal: make it as small as possible. But today’s focus is unrecognizable from past pursuits. Quantum computing, once doomed to theoretical discussions in musty physics buildings, is entering more and more into general discourse. AI has already fundamentally changed society, for better or worse, and classical supercomputers, which were once the pinnacle of technological achievement, are now one part of a much larger and more complex ecosystem.

Each of these computing paradigms—quantum, AI, and classical—is powerful in its own right, but IBM believes that the next era of computing is not about choosing one over the others. It’s about the sum of parts—in other words not OR, but AND. Bringing together interdisciplinary scientists under one roof creates an environment where collaboration and inspiration can flourish.

There is, of course, room for practicality here, too. This setup is not convenient for the sake of locality, but also in that testing multiple components together improves latency, a factor not to be overlooked in the performance of advanced computing systems.

As Zaira Nazario, director of Science and Technology in the Office of the Director of IBM Research, explains, “There are some quantum computations where you need classical computers very close by, because you need to be able to run things in a matter of hundreds of nanoseconds or microseconds.”

The Think Lab: A Lesson in Fluidity

The IBM Think Lab embraces a dynamic approach to research and development. While currently designed to accommodate the IBM Quantum System Two, prototype AIU chips, and future Z systems, the space can evolve and adapt as the needs of compute evolve and adapt. The modular design ensures that the lab can grow with the research it supports, making it a model that could be replicated at any institution with a need for advanced computing capabilities.

“You could be a national lab, or a pharmaceutical company that has a large research division, and you would need different types of systems to support the simulations that you need to do to discover drugs, and you want that to be modular so that it grows with user need,” Nazario said. This adaptability is key as scientific and technical revolution is undeniably fluid.

IBM’s vision extends beyond just the lab itself. They are also reimagining what data centers will look like in the future. No longer will they be cubic, metal wastelands, but instead, hybrid facilities that integrate quantum, AI, and classical computing, each system supporting different types of users and workloads that require some combinatorial synergy of them all.

It Takes a Village

The IBM Think Lab in Yorktown Heights creates a blueprint for the standard of research, one in which interdisciplinary collaboration and adaptable design can drive development. As the lab evolves, so too will the technologies it houses, growing and adapting in tandem with the needs of the researchers and industries it supports. In this space, where past architectural muses meet state-of-the-art paradigms, the next age of computation starts to take shape, one that is as fluid and dynamic as the challenges it seeks to solve.