Avid Video Gamer

Watching the highlights of the Fortnite World Cup from New York City last week made me think, quite coincidentally, as to where the quantum computer video game scene will be in a decade or two.

Because judging by the press, everybody and nobody knows.

As an avid video gamer myself (should my better half know that?)— playing most of the sports games out there — the Madden series being a particular favourite — has given me a layman’s inclination to find out how, when the technology is actually sophisticated enough, in what way quantum computer games will develop.

Decodoku

Up to the last year, the quantum computer gaming landscape was pretty barren — apart from James Wootton, an IBM quantum computing physicist and programmer, creating a game called Decodoku, courtesy of IBM’s hardware and software capabilities in the quantum computer space, there wasn’t a helluva lot out there.

Oh, and I nearly forgot to mention — before that he’d created a simple game of Battleships as well. The game, designed on a 5-qubit quantum computer and using partial NOT gates and utilizing IBM’s Qiskit open-source framework which uses Python computer language, was a kind of success as successes in quantum video games go.

Quantum Ferris Wheel

In February of this year, though, the ‘Quantum Game Jam’ took place in Helsinki, Finland. Unusually, the main event was on the Helsinki Skywheel, a Ferris wheel in the downtown district, or rather some of it was with the rest taking place in a building close to it away from the winter wind so famous in that part of the world. But surrealism aside, what’s more important is to know that where we are in respect to quantum gaming is 1962.

Know what’s so special about 1962?

Spacewar!, that’s what.

Back to the Beginning

Developed and created by computer scientist Steve Russell with help from Martin Graetz and Wayne Wiitanen on a DEC PDP-1 computer at the Massachusetts Institute of Technology, it eventually changed the world.

Pong, Pacman, Space Invaders. These were the games that birthed a paradigm shift and planted the seeds of a multibillion-dollar industry.

‘The game [Spacewar!] is “50 years old, with no outstanding user complaints, no catastrophic crashes, and it’s still available.’

— Steve Russell, creator of Spacewar!

Yet what’s important now is not Spacewar!’s entry into the gaming world but rather what Spacewar! is compared to quantum computers.

And Decodoku is no Spacewar!.

Even though its jolty movements and lame graphics in contrast to today’s wonderful video games like Resident Evil 2, Devil May Cry 5, Sekiro: Shadows Die Twice, and the stunning artistry of Dead or Alive 6 seem unfair as a judgment, what really matters is that we know where we are in terms of development.

We are 1962.

By that I mean Wooton’s Decodoku is 1962.

That is both a really good thing as well as a signal of how far we still have to go when it comes to game development in the discipline.

February’s event, however, was not just about Wootton. Other game developers, too, had a chance to work on their babies using IBM’s five and 16-qubit quantum computers. The event’s website states:

The Quantum Wheel — fifth Quantum Game Jam was a success! We had 50+ participants around the world and 10 teams finished their games in less than 48 hours!

Games Galore

The ten games, Q|Cards>, Quantum Fruit, SneaQySnake, Schrödinger’s Livingroom, Quantum Socket, h~a~m~s~t~e~r~w~a~v~e, Quabit the Barbarian, Qubit Gardener, Quantum Cabaret, and QSpell, all in their own way showed to the world what potential quantum computers will have in the future.

Graphics-wise, however, none the games were mindblowing, reminding me more of the 16-bit attempts I used to play on cassette as a boy on the ZX Spectrum in the 1980s when mullet-hair and the Brat Pack were all the rage.

‘So that was it. Battleships running on a quantum computer. Not the fanciest use of a quantum computer, or the fanciest version of Battleships. But for me, combining the two is half the fun!’

— Dr. James Wootton, ‘How to make Battleships from quantum NOT gates’, May 9, 2017

But maybe were onto something. Like Spacewar!, which gave rise to the hacking phenomenon that snowballed into a subculture of massive influence over the decades, you can be sure what Wootton and his quantum geeks in Finland have been doing will have far-reaching effects across the community on three key points:

Interest in it as a tool or form of entertainment.

Education on how it works.

The full adoption of it as a tool or form of entertainment that will fuel wide-scale use cases.

Happy Birthday, Mr Qubit!

We are still not there yet. What Qiskit offers is progress. Others, as well, like Rigetti’s Forest and the good work William Hurley (whurley) is doing currently with his open-source platform at Strangeworks, Inc, are signs the times are changing.

There’s nothing wrong with being in 1962. It was a good year: the Vietnam War had yet to start, the Beatles were about to conquer the world and Marilyn Monroe sang Happy Birthday to JFK.

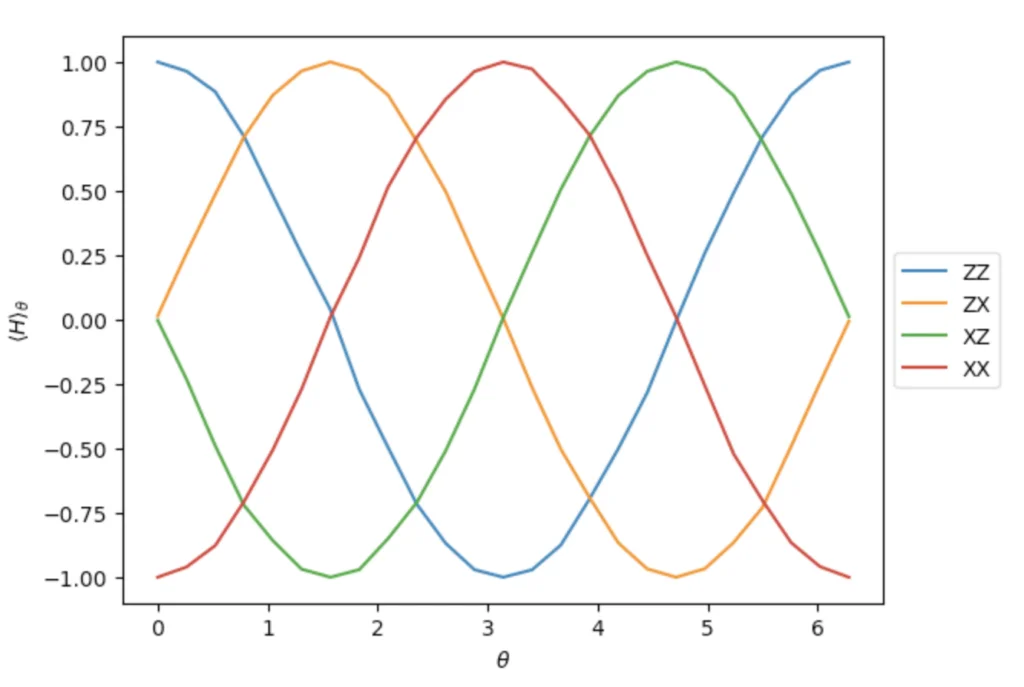

We just have to accept the quantum reality is here, but simulating molecules, replicating the human mind or formulating video games that are more real than reality itself is still some way off.

That doesn’t mean it won’t happen one day.

Because it will.