My name is Anders Liman. I’m a graduate student studying Tech Ethics and Science Policy at Duke University. I also hold a master’s in Computer Science from North Carolina State University. This summer, as part of a collaboration between Duke and Google, I researched the global quantum computing landscape in an effort to identify engagement challenges and opportunities in the field. This blog series is the fruit of this labor. You can find all the posts in the series written here:

Post 1 – Researching the global quantum computing landscape in an effort to identify engagement challenges and opportunities in the field

Post 2 – How scientific innovation and economic potential drive academic and industry efforts in quantum computing

Post 3 – How national security and digital sovereignty motivate governmental efforts in quantum computing

Post 4 – Competing interests, competing ideals, and unwanted hype in quantum computing, and ways to address them

Post 5 – Identifying NISQ applications, addressing workforce gaps, and developing future workforce in quantum computing

Post 6 – Properly framing quantum computing and setting appropriate expectations

Continuing our last post, we’ll focus on national security and digital sovereignty in this post. As a reminder, depending on the nation and sector, different stakeholders may articulate different motivations and to different degrees. Moreover, many stakeholders have more than one motivation.

Note: Each section includes representative stakeholders typifying the motivation, largely based on the stakeholders’ public disclosure, with which the actual/internal motivation(s) may or may not align. The lists are neither exclusive nor exhaustive.

National Security

The notion of national security is often mentioned as one motivation for QC R&D, especially in the US. It is, however, often unclear what is meant by national security. Therefore, this notion is further broken up into five sub-categories.

- Physical Security

Physical security often comes to mind when national security is mentioned. For some, physical security is the full extent of national security.

This motivation is often seen in the defense- and intelligence-focused departments and offices in governments. It is also noticeably more pronounced in the US government compared to other countries.

US: BIS, DARPA, DOD, IARPA, NSA;

CA: DND;

UK: Dstl, MOD;

DE: BMVg;

IL: MAFAT;

AU: ASPI.

- Economic Security

Economic security is related to but distinct from economic potential mentioned above. Economic security emphasizes a nation’s sustainable economic wellbeing and international competitiveness.

This motivation is most often found in economic-focused departments and offices in governments.

Economic security and physical security are jointly responsible for export control measures and university limitations for Chinese nationals, especially in the US. Some have expressed that these measures are harmful to scientific innovation and likely to hamper US technology leadership in the long term.

US: BIS, ESIX, NIST, OSTP;

CA: ISED;

UK: BEIS;

DE: BMWK;

AU: ASPI.

III. Energy Security

Energy security focuses on a nation’s ability to sustainably produce and provide energy for its citizens.

This motivation is often shared among energy-focused departments and offices in governments.

US: DOE;

UK: BEIS;

FR: CEA;

RU: Rosatom;

AU: Department of Industry, Science, Energy and Resources.

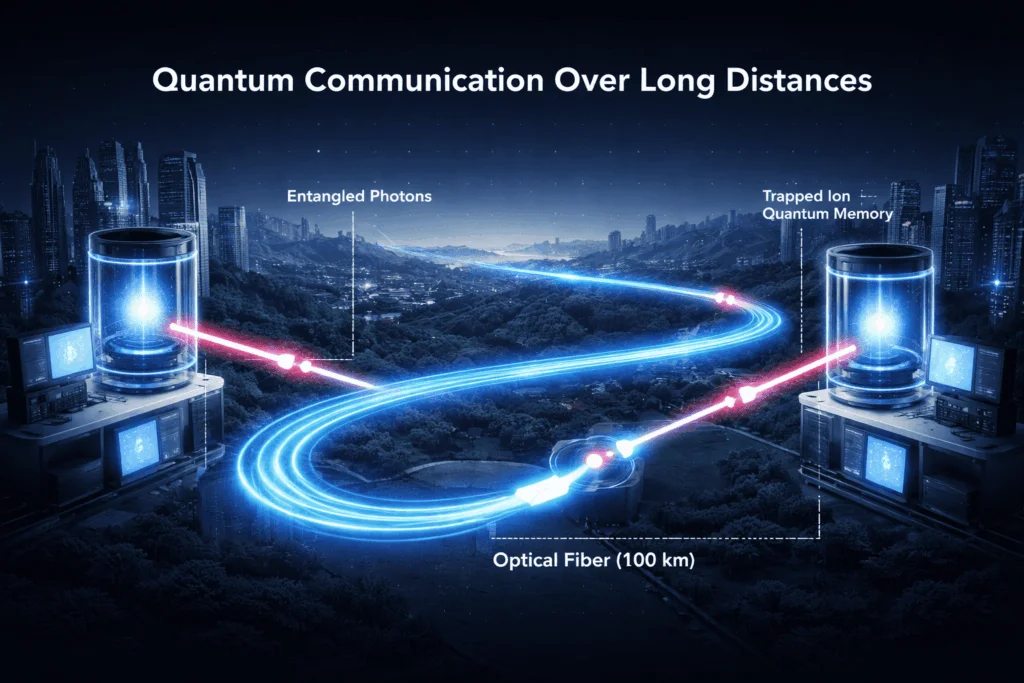

- Cybersecurity

Cybersecurity is one of the most discussed considerations in QC. This is largely due to Shor’s algorithm that theoretically proved quantum computers’ capability to factor large numbers much faster than classical computers – which would break RSA encryption.

This motivation is often seen alongside physical security and other national security motivations. It is also one of the first concerns to emerge when discussing QC with virtually any stakeholder.

US: DARPA, DHS, DOD, IARPA, NIST, NSA;

UK: Dstl, MOD, NCSC;

DE: BSI.

- Environmental Security, Infrastructure Security, & Political Security

Environmental, infrastructure, and political security are other facets of national security that are less prominent when discussing QC. Nevertheless, these are related to and somewhat dependent on the other four notions of national security.

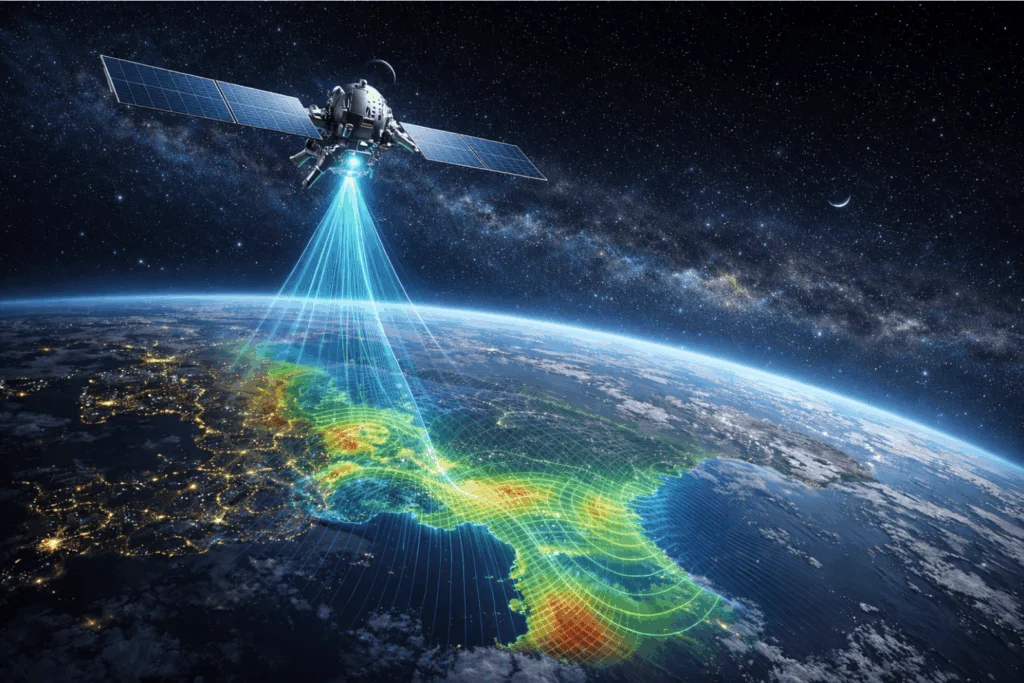

Digital Sovereignty

Digital sovereignty is another notion that may be ambiguous and unfamiliar, especially for American readers. Broadly speaking, digital sovereignty denotes a nation state’s independence in relation to other states (i.e., external sovereignty) and its supreme authority to govern within its territory (i.e., internal sovereignty) in the digital space. Oftentimes, this translates to owning and/or independently operating certain technologies. A drive for digital sovereignty is often motivated by some of the aspects of national security outlined above, but usually with more of an emphasis on economic security and less on physical security.

This motivation is most often found in EMEA governments, especially in France and Germany. The degree of emphasis may vary depending on both the perceived importance and government style. For example, Russia emphasizes digital sovereignty and heavily regulates and controls investments, while the UK sometimes mentions it and takes a light-touch regulatory approach. While not phrased exactly the same way, this motivation is one of the driving motivations in the Chinese government. Notably though, this motivation is largely absent in other APAC and NAM countries.

While the digital sovereignty rhetoric has fostered the health of multiple startups across the EU, some have argued this rhetoric may lead to governments only funding and working with startups in their respective nations. Instead of supranational or global collaborations that may produce a handful of elite QC solutions, an overemphasis of digital sovereignty is more likely to result in dozens of subpar solutions.

General governmental rhetoric to varying degrees in the EU, FR, DE, UK, RU, and CN.

Next Up

Post 4 – Competing interests, competing ideals, and unwanted hype in quantum computing, and ways to address them

Looking Ahead

Post 5 – Identifying NISQ applications, addressing workforce gaps, and developing future workforce in quantum computing

Post 6 – Properly framing quantum computing and setting appropriate expectations

Previously

Post 1 – Researching the global quantum computing landscape in an effort to identify engagement challenges and opportunities in the field

Post 2 – How scientific innovation and economic potential drive academic and industry efforts in quantum computing

Acknowledgements

The author would like to express sincere gratitude to the following organizations and individuals for their valuable insights which prove integral to the creation of this blog series: Google Quantum AI team, Google Government Affairs and Public Policy team, Thomas Monz (AQT), Christina C. C. Willis (ColdQuanta), Lamont Silves (IonQ), Ken Brown (Duke University), Jonathan Felbinger (QED-C / SRI International), Carl Williams (CJW Quantum Consulting), Matt Trevithick (DCVC), and David Moehring (Cambium Capital).

The author would also like to express sincere gratitude to the following individuals for their support and counsel throughout the research: Kate Weber (Google), Ashley Zlatinov (Google), Charina Chou (Google), Lee Tiedrich (Duke University), and Buz Waitzkin (Duke University).

For more market insights, check out our latest quantum computing news here.