IBM’s quantum computer — the Q System 1 — is practically just out of the wrapper, but, according to Nature Biotechnology, it’s already getting an important first mission: helping cancer researchers in Europe,

The device, billed as one of Europe’s most powerful commercial quantum computers, is located at IBM’s German headquarters in Ehningen, near Stuttgart and jointly operated by IBM and the Fraunhofer Society, Germany’s multidisciplinary applied research organization.

The Fraunhofer Society will allow researchers to use the The 27-qubit quantum computer to test ideas for practical applications of quantum computers.

Biomedicine makes a natural fit for quantum computing because of the computationally intense and complex questions faced by researchers in the field. The Fraunhofer Society hopes cancer researchers, among others, will use the device to explore research questions in oncology.

It’s a big — and uncertain — first step.

“It’s uncharted territory,” oncologist Niels Halama of the DKFZ, Germany’s national cancer center in Heidelberg, told Nature Biotechnology.

Halama is working with a team of physicists and computer scientists to develop and test algorithms that might help stratify cancer patients. The team will select small subgroups for specific therapies from heterogeneous data sets.

This is the beginning of precision medicine, something that classical computing struggles to accomplish. Classic computing lacks the power to find small groups in the large and complex oncology data sets. The task, which can take weeks to accomplish on a regular device, isn’t practical for doctors in a clinical setting and would be cost prohibitive, the journal states.

With the end of Moore’s Law potentially nearing, these limits may be intractable.

“There is no guarantee that the quantum system will deliver the solutions we want. But there are indications that merit follow-up.”

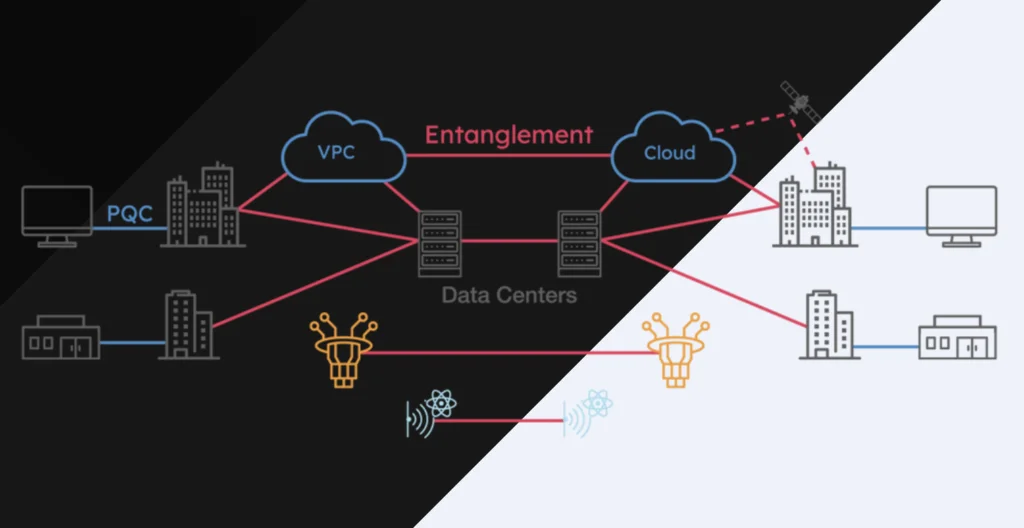

While quantum faces its own challenges, researchers want to explore whether quantum, which theoretically could be speedier and more robust than classic, can deliver some of these solutions that precision medicine needs.

The researchers understand that noise — the ability of the environment to affect the calculations of extremely sensitive quantum devices — is the most significant challenge of quantum precision medicine.

“There is no guarantee that the quantum system will deliver the solutions we want,” he tells Nature Biotechnology. “But there are indications that merit follow-up.”

Hamala will use two different approaches. The team will create machine learning algorithms ffor quantum processing that might require smaller training datasets than conventional computing. It’s an approach taken for human tumor data from the Cancer Genome Atlas. The other approach will use algorithms based on different mathematics—topological algebra, which quantum computing handles well—to sift through data for interesting patterns.

“Quantum computing will become a tool of the trade for someone like me.”

There’s no reason that quantum computing would be restricted to just oncology. The devices may be vital to research in computational chemistry and biomedicine, and, in fact, across the life sciences.

Computational biologist Charlotte Deane, University of Oxford, told the journal she is taking this approach in her work on protein folding.

“It will speed up a limited number of tasks for us, and we need to correctly identify those tasks now,” Deane said.

Deane is optimistic about quantum’s potential.

“Quantum computing will become a tool of the trade for someone like me,” Deane told the journal.

All research projects and user data remain in Germany, and the IBM Q System One operates in accordance with Germany’s strict data-protection law, according to the journal.

The Q System 1 was just installed over the summer.

For more market insights, check out our latest quantum computing news here.